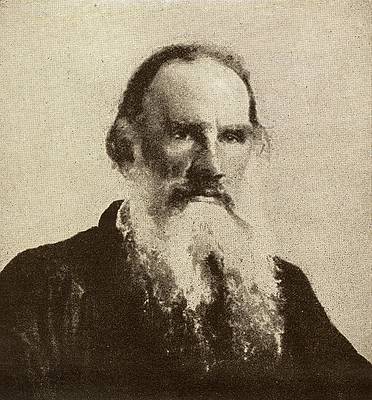

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1852

Source: Original Text from WikiSource.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

" My God ! My God ! " thought Nekhlyudov, making his way with long strides to the house through the shady avenues of the weed-grown garden, and absent-mindedly tearing off leaves and branches on his way. " Is it possible all my dreams of the aims and duties of my life have been absurd ? Why do I feel so oppressed and melancholy, as though I were dissatisfied with myself, whereas I had imagined that the moment I entered on the path, I would continually experience that fullness of a morally satisfied feeling which I had experienced when these thoughts came to me for the first time ? "

He transferred himself, in imagination, with extraordinary vividness and clearness, a year back, to that blissful moment.

He had risen early in the morning before everybody in the house, painfully agitated by some secret, inexpressible impulses of youth ; had aimlessly walked into the garden, thence into the forest ; and, amid the strong, luscious, but calm Nature of a May day, he had long wandered alone, without thought, suffering from an excess of some feeling, and unable to find an expression for it.

His youthful imagination, full of the charm of the unknown, represented to him the voluptuous image of a woman, and it seemed to him that this was the unexpressed desire. But another higher feeling said to him, " Not this," and compelled him to seek something else. Then again, his vivid imagination, rising higher and higher, into the sphere of abstractions, opened up to him. as he thought, the laws of being, and he dwelt with proud delight upon these thoughts. And again a higher feeling said, " Not this," and again caused him to seek and be agitated.

Without ideas and desires, as always happens after an intensified activity, he lay down on his back under a tree, and began to gaze at the translucent morning clouds, which scudded above him over the deep, endless sky. Suddenly tears stood, without any cause, in his eyes, and, God knows how, there came to him the clear thought, which filled his soul, and which he seized with delight, — the thought that love and goodness were truth and happiness, and the only truth and possible happiness in the world. A higher feeling did not say, " Not this," and he arose, and began to verify his thought.

" It is, it is, yes ! " he said to himself in ecstasy, measuring all his former convictions, all the phenomena of life, with the newly discovered and, as he thought, entirely new truth. " How stupid is all which I have known, and which I have believed in and loved," he said to himself. " Love, self-sacrifice, — these constitute the only true happiness which is independent of accident ! " he repeated, smiling, and waving his hands. He applied this thought to life from every side, and he found its confirmation in life, and in the inner voice which told him, "It is this," and he experienced a novel feeling of joyful agitation and transport. " And thus, I must do good in order to be happy," he thought, and all his future was vividly pictured to him, not in the abstract, but in concrete form, in the shape of a landed proprietor.

He saw before him an immense field of action for his whole life, which he would henceforth devote to doing good, and in which he, consequently, would be happy. He would not have to look for a sphere of action : it was there ; he had a direct duty, — he had peasants —

What refreshing and grateful labor his imagination evoked : " To act upon this simple, receptive, uncorrupted class of people ; to save them from poverty ; to give them a sufficiency ; to transmit to them the education which I enjoy through good fortune ; to reform their vices which are the issue of ignorance and superstition ; to develop their morahty ; to cause them to love goodness — What a brilliant and happy future ! And I, who will be doing it all for my own happiness, shall enjoy their gratitude, and shall see how with every day I come nearer and nearer to the goal which I have set for myself. Enchanting future ! How could I have failed to see it before ?

" And besides," he thought at the same time, " who prevents my being happy in my love for a woman, in domestic life ? "

And his youthful imagination painted a still more entrancing future to him.

" I and my wife, whom I love as no one in the world has ever loved, will always live amid this tranquil, poetical country Nature, with our children, perhaps with an old aunt. We have a common love, the love for our children, and both of us know that our destiny is goodness. We help each other to walk toward this goal. I take general measures, furnish general and just assistance, start a farm, savings-banks, factories; but she, with her pretty little head, in a simple white dress, lifted over her dainty foot, walks through the mud to the peasant school, to the hospital, to some unfortunate peasant, who really does not deserve any aid, and everywhere she consoles and helps — The children and the old men and women worship her, and look upon her as upon an angel, a vision. Then she returns home, and she conceals from me that she has gone to see the unfortunate peasant, and has given him money ; but I know everything, and I embrace her tightly, and firmly and tenderly kiss her charming eyes, her bashfully blushing cheeks, and her smiling ruddy lips — "