The Child and his Behavior. A. R. Luria

For its first few years, the child lives a primitive closed existence, seeking to forge the most elementary and primitive links with the world.

As we have already seen, the child for its first few months is an asocial narrowly organic creature, cut off from the external world and wholly limited to his physiological functions. For the small child, the whole world is limited primarily to the confines of his own organism and to whatever brings him pleasure. It has been virtually unnecessary for him to come into contact with the external world at all; living a generally parasitic existence, he has yet to encounter those limitations and obstacles posed by reality; to a large extent his perception of the world is still primitive, and, as we have just seen, he still mingles the primitive action of his imagination and traces of previous experience with reality.

All of this, of course, cannot fail to exert a decisive influence on the child’s thinking. We must make it quite clear that the thinking of a small child, 3-4 years of age, has nothing in common with the forms of adult thinking that have been created by culture and lengthy cultural evolution, as well as by repeated and active encounters with the external world.

This certainly does not mean that the thinking of the child lacks its own laws; it has some quite definite laws, wholly unlike those governing the thinking of adults. Between the ages of 3 and 4, the child has his own primitive logic, and his own primitive thinking devices – all of which are shaped by the fact that this thinking takes place in the primitive medium of a type of behavior that has yet to engage in serious contact with reality. Until very recently, we knew little about these laws that govern the thinking of the child; in fact it was only in the past few years, particularly as a result of the work of the Swiss psychologist Piaget, that we have learned of their main characteristics. A most curious picture emerged: after a number of studies it became clear not only that the thinking of the child is governed by laws, quite unlike those that apply to adults, but that its structure and resources are also radically different.

If we ponder the kind of functions performed by adult thinking, we soon conclude that it organizes our adaptation to the world in especially complex situations. It governs our attitude to reality in particularly complex cases where mere instinct or habit will not suffice. In this sense, thinking is a function of proper adaptation to the world, and a form which organizes our efforts to act upon the world. These factors determine the whole structure of our thinking. In order for us to be able to act upon the world in an organized manner, it must work as correctly as possible; it must not become separated from reality, or merge with fantasy; and each step it takes must successfully withstand practical verification. The thinking of a healthy adult meets all these requirements; only in persons afflicted with neuro-psychological disorders may thinking assume other forms, not connected to real life, and incapable of organizing a proper adaptation to the world.

This is not at all what we find in the first stages of the development of the child. The extent to which his thinking follows the correct course, or withstands the first check, the first encounter with reality, is frequently of no concern to the child. His thinking frequently does not seek to regulate and organize a proper adaptation to the external world, and even when it occasionally begins to pursue such ends, it does so primitively, having at its disposal deficient tools which still require lengthy development before they can be of practical benefit.

Piaget finds that the thinking of the small child (3-5 years) has two main traits: egocentricity and primitiveness.

We have already said that the behavior of the infant is characterized by the fact that he is typically cut off from the world, and engrossed in himself, his interests and his pleasures. Just watch a child aged 2-4 playing by himself: he pays attention to nobody; being entirely immersed in himself, he will lay out certain objects before him and then pull them all together again, talking to himself, and both addressing and answering himself. It is difficult to distract him from his playing; if you speak to him he will not stop what he is doing immediately. At this age a child can quite well play all alone, totally absorbed in himself.

Here is a transcript of a child of 2 years 4 months engaged in this kind of play:[8]

Marina, aged 2 years 4 months, was entirely engrossed in play: she would pour sand on her legs, mainly above the knees, and then pour it into her socks, then she would pick up handfuls of sand and spread it with an open palm over her leg. Eventually she started pouring sand on her thigh, covering it with a handkerchief from the top and pressing it with both hands around her leg. She looked contented, and often smiled to herself.

While playing, she often talked to herself, saying: Mama, there...more ... more ... Mama keep pouring ... more, Mama... pour Mama... Mummikins keep on pouring... no matter ... that’s my aunt... auntie, more sand... auntie... the doll needs more sand.

This egocentricity in the thinking of the child may also manifest itself in other ways. Let us try to observe when and how children talk, as well as the purposes of their conversations and the forms they take. On closer scrutiny, we will be surprised to find the extent to which the child talks alone, “into space”, or to himself, and how often he does not use speech as a means of communicating with others. One gets the impression that the child often does not use speech for the social purposes of mutual discourse and information, as is the case with adults.

Here is another transcript of the behavior of a child, that we have borrowed from the same source. We wish to draw attention particularly to the way the play of a child of 2 years 6 months is accompanied by “autistic” speech, addressed solely to himself.

Alik, aged 2 years 6 months (on entering his mother’s room), began to play with some rowanberries, plucking them off the stem and piling them up in the slop-basin: “Got to clean the berries right away... They're my berries – they're lying on the bed. (Notices a wrapper from a jam jar). No more jam? Only the paper left? (Eats some jam). Jam’s nice. Nice jam (eats jam). Jam’s nice. It’s fallen down! A drop has fallen down! It’s so small...big ... a little cube ... it can sit there, the cube ... it can sit too...it can’t write ... the cube can’t write ... (picks up the milk jug). Let’s put some matches in there, and give them a pie (picks up a circular piece of cardboard). Lots of pies ...”

Piaget, to whom we have already referred, established that the most typical form of speech for the child is in fact the monologue, in which one talks to oneself.

The child continues to use this form of speech even when in company; it can assume some specific and rather comical forms as each child, even when in company, continues to develop his own ideas, paying only scant attention to his “interlocutors” who (if the children are the same age as him) ... are also engaged in monologues.

Piaget writes, ‘The child talks in this way, and usually does not care if his interlocutors are listening to him, simply because he is not really addressing them at all. In fact he is not addressing anybody. He is talking out loud to himself in the presence of others.” [9]

We are accustomed to viewing speech in company as providing a link between people. Yet we frequently find that among children this is not so. Here is another transcript, this time of the conversation of a child aged 6% in the company of others of the same age, while at play drawing. [10]

P. aged 6 years, (speaking to Z.), who is drawing a tramcar with a trailer:

23. “But trams don’t have platforms when they're towing trailers.” (No reply).

24. (Talks about the tram he has just drawn). “They don’t have cars in tow.” (Does not address anybody. Nobody replies).

25. (speaking to B.) “It’s a tram, it doesn’t have any cars.” (No reply).

26. (speaking to K.). “This tram doesn’t have any cars, K., you know, you know, it’s red, you know.” (No reply).

27. (L. speaks aloud: “What a funny man plays after a pause, and not speaking to R, or anyone at all.) P: “There’s a funny man.” (L. goes on drawing his tram car).

28. “I'm going to leave my tram car white,”

29. (Z., a girl, who is also drawing, declares: “I shall make it yellow.”) “No, there’s no need to make it yellow.”

30. “I'm going to make some stairs, look.” (B. replies: “I can’t come tonight, I've got gym... “).

The main feature of this conversation is the virtual absence of what we have grown accustomed to viewing as the basic component in a conversation among several people: a mutual discourse involving questions, answers and opinions. This element is almost entirely lacking in the above passage. Each child is talking principally about or to himself, without addressing anybody or expecting any replies from anybody. As he does not receive a reply even when he expects one, he quickly forgets about it and moves on to the next “conversation”. For a child of this age, speech is only partly a tool for mutual communication; the remainder of such a child’s speech has not yet become “socialized”. It is “autistic”, and egocentric; and, as we shall see in due course, its role in the child’s behavior its entirely different.

Piaget and his associates have also drawn attention to a number of other forms of speech of an egocentric character. On closer scrutiny it becomes evident that even many of the child’s questions are egocentric in nature: he asks a question, already knowing the answer, just for the sake of asking, in order to make his mark. There are rather a large number of egocentric forms in the speech of children; according to Piaget: from age 3-5 their proportion varies on average between 54 and 60 percent, and from 5-7 between 44 and 47 percent. These figures, based on lengthy and systematic observation of children, show how specifically structured are the thought and speech of children, and how markedly the function and character of children’s speech differ from those found in adult speech. [11]

It was not until very recently, through a special series of experiments, that we became convinced that egocentric speech performs quite definite psychological functions, principally in the planning of actions already begun. In this case, speech begins to play a highly specific role, entering into functionally, special relationships with the other acts of behavior. The two passages quoted above make it quite clear that speech activity in the child is not merely an egocentric phenomenon, but that it also obviously serves for purposes of planning. It is easy to elicit such an outburst of egocentric speech by blocking the flow of some process in which the child is engaged. [12]

Forms of speech are not, however, the only area in which the primitive egocentrism of children’s thinking manifests itself. Egocentric traits figure even more prominently in the contents of the child’s thinking, and in his fantasies.

Arguably, the plainest manifestation of the child’s egocentrism is the fact that the small child is still living wholly inside a primitive world, whose criterion is satisfaction and dissatisfaction, and into which reality intrudes to a very insignificant extent. As far as one can tell from the behavior of the child, that world is characterized by the existence, wedged between him and reality, of another, half-real intermediate world highly typical of the child – that of egocentric thinking and fantasy.

If any of us, as an adult, collides with the external world while satisfying some need, and then finding that our need remains unsatisfied, we organize our behavior in such a way as to satisfy that need, by means of a cycle of organized actions, or, reconciling ourselves to necessity, we abandon our efforts to satisfy that need.

None of this is true of the small child. Being incapable of organized actions, he follows his own peculiar path of least resistance: if the external world will not give him something in real terms, he remedies that lack in his fantasy. Being incapable of reacting properly to any delay in meeting his needs, he reacts improperly, by creating for himself an illusory world where his wishes are met and where he is fully in charge, and the center of the universe he has created; he creates a world of illusory egocentric thinking.

For adults, such a “world of fulfilled wishes” remains in the province of dreams, whereas for the child it is “a living reality.” As we have shown, he is perfectly content to replace real activity with play or fantasy.

Freud mentioned one boy whose mother told him he was not allowed to have cherries. First thing next morning he announced that he had eaten all the cherries and was very pleased to have done so. Actual dissatisfaction had been remedied in the illusion of a dream.

Fantastic and egocentric thinking in children does not, however, manifest itself only in dreams. It is particularly evident in their “daydreaming”, which is often mixed with play. This in fact is the source of what we often interpret as children’s lies, as well as a number of peculiarities of the thinking of the child.

When a 3 year old child, in answer to the question, “Why is it light in the day, and dark at night?”, says, “Because people eat in the day, and sleep at night”, he is of course manifesting that same egocentric and practical approach which explains everything as being adapted for him and for his benefit. We may say the same about those naive representations one finds in children, to the effect that everything around them – including the sky, the sea and the cliffs – are all man-made and can be given as a gift;[13] we also find the same egocentric principle and wholehearted faith in the omnipotence of adults in the child who asks his mother to give him a pine grove, or the village of B., where he would like to go, or to cook spinach in such a way as to get potatoes, etc.[14]

When little Alik (2 years) happened to see a car that he liked very much driving by, he began nagging his mother: “Mama, make it go by one more time!!” Marina (also aged about 2) reacted in the same way to the sight of a crow flying past: she was quite convinced that her mother could compel the crow to fly by once more.[15]

This tendency has a curious influence on children’s conversations and reactions to them, as can be seen from this transcript of one conversation with a child:[16]

Alik (5 years, 5 months).

One evening, looking out the window, he saw Jupiter.

– Mum, what’s Jupiter for?

I tried to explain, but to no avail. He pressed his inquiry.

– Well then, what’s Jupiter for?

At this point, not knowing how to respond, I asked him:

– What are we for?

To which I received an immediate and confident reply.

– For ourselves.

– Alright then, Jupiter is also for itself.

He liked this answer and said contentedly:

– And the ants, bedbugs, mosquitoes and stinging nettles, they're also just for themselves?

– Yes.

And he laughed gleefully.

The primitive teleologism shown by the child in this conversation, is highly characteristic. Jupiter has to exist for some purpose or other. In the child’s mind this “for what?” usually takes the place of the more complex “why?”. When the answer to that question turns difficult, the child still manages to find a way out. The notion that we exist for ourselves, an answer that typifies the peculiar teleological thinking of the child, nonetheless enables him to solve the problem of what other things and animals exist for – even those he finds unpleasant (ants, bedbugs, mosquitoes and stinging nettles ... ).

Lastly, the influence of that same egocentricity may be discerned in the child’s characteristic attitude to the conversation of others and the phenomena of the external world: he sincerely believes that nothing is beyond his understanding, and we hardly ever hear the words “I don’t know” from the mouth of a 4-5 year old. As we shall see, the child finds it difficult to hold back the first decision that comes into his head, and finds it easier to make an absurd reply than to admit ignorance.

The ability to inhibit one’s immediate reactions and to delay one’s response in time is the product of development and training, which does not occur until much later. After all that we have said about egocentricity in the child’s thinking, it will come as no surprise if we say that the thinking of the child also differs from that of the adult by virtue of its logic, and that it is based on the “logic of the primitive”.

It is naturally out of the question for us, in a brief digression such as this, to give anything like a full description of this primitive logic that characterizes the child. We shall merely dwell on those of its features that are readily discernible in the conversation and opinions of children.

As we have seen, the child, being egocentrically disposed toward the external world, perceives external objects concretely and integrally, concentrating on those aspects that concern him and act directly upon him. Naturally, the child has yet to elaborate an objective attitude to the world, transcending the concrete perceived features of the object and focussing on objective relationships and patterns. He takes the world as he perceives it, not bothering about the links between individual perceived pictures, or the construction of that systematic picture of the world and its phenomena that a civilized adult, whose thinking must govern his relationship with the world, finds necessary and indispensable. In the primitive thinking of the child, this logic of relationships, causative links, etc., is precisely what is lacking, its place taken by other primitive logical devices.

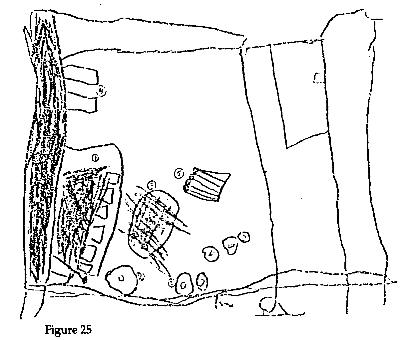

We shall now turn once again to the speech of the child, and consider how the child expresses those dependences whose presence in his speech is of interest to us. Many authors have already observed that the small child never uses subordinate clauses; he does not say, “When I went out for a walk, I got wet because there was a thunderstorm.” Instead, he will say, “I went out for a walk; then it started raining, then I got wet.” Causative links are usually missing in the speech of the child, the connection “because” or “consequently” being replaced by the conjunction “and”. Such defects in the formulation of speech clearly cannot fail to have an impact on his thinking: a complex systematic picture of the world, in which phenomena are arranged according to the links and causative dependences between them, is supplanted by a simple “gluing together”, or primitive joining, of discrete features. These devices of the child’s thinking are clearly reflected in his drawings, which are also based on the same principle of the enumeration of discrete parts with no special links between them. This is why one often sees in children’s drawings pictures of eyes, ears or a nose separate from the head, or next to it, but not connected to it and not subordinate to a general structure. We have presented a number of examples of such drawings. The first of these (Figure 23) was done not by a child, but by an Uzbek woman with a low cultural level, who nonetheless repeats the features typical of the thinking of the child with such extraordinary clarity that we have ventured to reproduce this example here.[17]

It is supposed to depict a man on a horse. It is at once evident that the artist has not copied reality, but has been guided in her drawing by certain other principles, and by a different type of logic. As a careful scrutiny of the drawing will reveal, the most remarkable thing about it is the fact that its underlying principle is not that of the system “man” and “horse”. Here the underlying principle is the gluing together, or mere compilation of the discrete features of a man, with no attempt to synthesize them into a single image. In the drawing we see a separate head, and. lower down, a separate ear, eyebrows. eyes, nostrils, in nothing like their true relative positions, enumerated in the drawing as discrete and sequential parts. The legs, shown in the bent position, as experienced by the horseman, and the sexual organ shown quite apart from the body are all depicted here naively pasted or strung together.

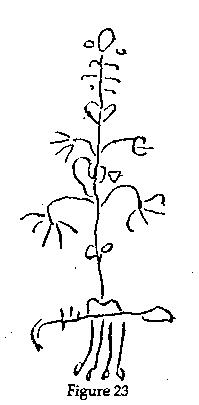

The second drawing (Figure 24) was done by a 5 year-old boy. The child was trying to draw a lion, and inserted the appropriate explanatory notes in the drawing.

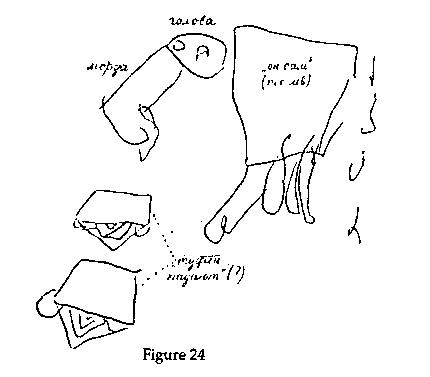

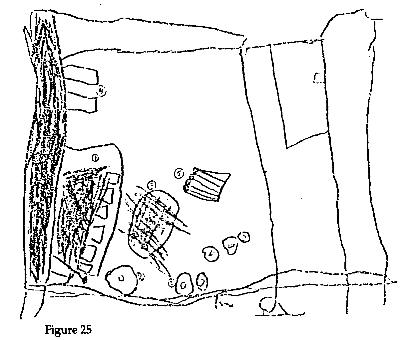

He drew a separate “muzzle”, and a separate “head” while labelling all remaining parts of the lion as “him”. There are of course, far fewer details in this drawing than in the first (a fact fully consonant with the peculiarities of perception in children of that age), but the same element of “pasting” is again readily apparent. It is particularly obvious in drawings in which the child tries to depict some complex set of things, such as a room. Figure 25 is an example of how a 5 year old tries to depict a room containing a stove giving off heat.

This picture is clearly characterized by the “pasting” of discrete objects related to the stove: here we see the firewood ready for use, the dampers, the stove door, and a box of matches (these are huge, in keeping with their functional role): all of this is shown as an aggregate of discrete objects, laid out side by side and strung together.

It is precisely this “strung togetherness”, in the absence of strict governing patterns and orderly relationships, that Piaget considers characteristic of the thinking and logic of the child. Being virtually unaware of any categories of causality, the child links effects, causes and consequences, as well as discrete phenomena unrelated to them, one after another in random sequence. This is why cause and effect frequently switch places in the child’s mind, and why a child familiar only with such primitive precultural thinking proves helpless when confronted with a conclusion prefaced with the word “because”.

Piaget conducted experiments in which the child was given sentences ending with the word “because”, after which he was then supposed to supply the missing reason. The results of these experiments prove highly typical of the primitive thinking of the child. Here are some examples of such “judgments” of the child (the answers added by the child are shown in italics).

Ts. (7 years 2 months): A man fell in the street because... he broke his leg and they had to make a stick for him instead of it.

K. (8 years 6 months): A man fell off a bike because... he broke his arm.

L. (7 years 6 months): I went into the bathroom because... I was clean later on.

D. (6 years): I lost my pen yesterday because... I don’t write.

As we can see, in each case the child confuses cause and effect, and finds it virtually impossible to arrive at the correct answer. The kind of thinking that functions correctly through the category of causality proves wholly alien to the child. The category of purpose proves much closer to him – and this seems perfectly natural if we recall his egocentric disposition. For example, the way one of Piaget’s young experimental subjects constructs his sentence reveals the essence of his logic.

D. (3 years 6 months): “I shall start the stove ... because ... so as to get warm.”

This example clearly illustrates both the phenomenon of the “stringing” together of discrete categories, and the substitution of the more familiar category of purpose for that of causality, which is alien to the child.

Such a “stringing together” of discrete representations in the thinking of the child is also evident in the fact that the child’s representations are not arranged in a definite order of importance (broader concept – part of that concept narrower concept, etc., as in the typical series genus – species – family, etc.); instead, discrete representations seem to him to be virtually synonymous.

There is, for example, the small child who sees no substantial difference between town, district and country. For him, Switzerland is roughly similar to Geneva, only farther away; France is roughly similar to his home town, only even farther away. He fails to understand that a person, while being a citizen of Geneva, can at the same time be Swiss. Here is a brief conversation quoted by Piaget that illustrates this peculiar “plane” of the child’s thinking.[18] The conversation reproduced here takes place between the instructor and the young Ob., aged 8 years 2 months.

– Who are the Swiss?

– They're the people who live in Switzerland.

– Is Fribourg in Switzerland?

– Yes, but I'm neither a Fribourgeois nor a Swiss...

– What about the people who live in Geneva?

– They are Genevois.

– And the Swiss?

– I don’t know... I live in Fribourg, it’s in Switzerland, but I'm not Swiss. Nor are the Genevois ...

– Do you know any Swiss?

– Very few.

– Yes.

– Where do they live?

– I don’t know.

This conversation makes it abundantly clear that the child is still unable to think in logical and consequential terms, and obviously does not realize that concepts pertaining to the external world may be arranged in several layers, or that an object may simultaneously belong to a narrow group and to a broader class. The child thinks concretely, perceiving the most familiar aspects of things, and wholly lacking the ability to take a more abstract view of them and realize that in addition to their other features, they may also belong to other phenomena. In this respect we may say that the thinking of the child is always concrete and absolute; the example of this primitive thinking of the child enables us to identify the distinctive traits of the primary, prelogical phase in the development of thought processes.

We have observed that the child thinks in terms of concrete things, but has difficulty grasping the relationships between them. A child of 6-7 years can tell his right hand from his left with confidence, but finds it quite incomprehensible that one and the same object can simultaneously be right in relation to one thing, and left in relation to another. A child who has a brother is similarly perplexed by the notion that he himself is a brother to him When asked how many brothers he has, a child may answer that he has one brother, and that his name is Kolya. We then inquire, “How many brothers does Kolya have?” The child is silent, and then announces that Kolya has no brothers. We can be quite sure that even in such simple cases the child cannot think relatively, and that primitive, precultural forms of thought are always absolute and concrete. Relative thinking, which is capable of transcending such absoluteness, is the product of a high degree of cultural development.

We wish to emphasize one more feature of the thinking of small children. It is only to be expected that a huge proportion of the words and concepts with which the child comes into contact will be new and incomprehensible to him. Even so, adults use them; and in order to catch up and not seem less intelligent or at a loss, the child devises a unique method of adaptation, which spares him the feeling of inferiority and enables him, at least superficially, to master expressions and concepts he finds incomprehensible. Piaget, who thoroughly studied this mechanism of the thinking of the child, calls it syncretism. This term applies to an interesting phenomenon, traces of which occur in adults, but which flourishes lavishly in the psyche of the child. It involves the ready ability to assimilate concepts that are only externally similar, and to replace an unfamiliar concept with another that is more familiar.

Such substitution of the intelligible for the unintelligible, and such merging of meaning is quite common in children. K. Chukovsky, in an interesting book, gives us a number of very clear examples of this syncretic mode of thinking. [19] When little Tanya was told that there was rust (rzhavchina) on her brocade, she did not bother to ponder the meaning of this new word, but said that a horse had neighed (narzhala) at her. For young Russian speaking children, a horseman (vsadnik) is “a man in the garden” (sad); an idler (lodyr) is “a person who makes boats” (lodki); and an almshouse (bogadelnya) is “a place where they make God” (bog).

The mechanism of syncretism is highly characteristic of the thinking of the child, for obvious reasons: it is the most primitive mechanism, without which the child would find it difficult to take his first few steps in primitive thinking. At each step, new difficulties await him, new incomprehensible words, thoughts and expressions. And of course he is not a scientist or a scholar; he cannot go every time to his dictionary or consult an adult. He can preserve his independence only by means of primitive adaptations, syncretism being such an adaptation, one nurtured by the child’s inexperience and egocentricity.[20]

How does the process of thinking take place in the child? What laws does the child follow in arriving at conclusions and forming judgments? All that we have said so far makes it abundantly clear that from the child’s point of view there is no such thing as highly developed logic, with all the limitations it imposes on thought, and with all its complex conditions and patterns. The primitive precultural thinking of the child has a far simpler structure: it is a direct reflection of the naively perceived world. All the child needs is one detail or one incomplete observation to draw the corresponding (though entirely wrong) conclusion. Whereas adult thinking is governed by the laws of a complex combination of accumulated experience and conclusions drawn from general premises, and is subordinate to the laws of inductive-deductive logic, the thinking of the small child, on the other hand, is what the German psychologist Stern has described as “transductive”. It does not proceed from the particular to the general, nor from the general to the particular; it merely concludes from case to case, each time on the basis of new, readily evident features. In the mind of the child each phenomenon receives a corresponding explanation which is supplied immediately, bypassing any logical stages or generalizations.

Here is an example of this kind of conclusion:

Child M. (8 years) was shown a glass of water, into which a stone was placed, raising the level of the water. When asked why the water had risen, the child answered: “because the stone was heavy.”

We then took another stone, and showed it to the child.

M. – “It’s heavy. It will make the water rise.”

– And this (smaller) one?

M. – “No, that one won’t do it...”

– Why?

M. – “It’s light.”

We can see that the conclusion is reached instantaneously, from one particular case to another, the basis for it being one of several arbitrary features. The lack of any conclusion from a general premise is well illustrated by the continuation of the experiment.

The child is shown a piece of wood.

– Is this piece heavy?

– No.

– If it’s put in the water, will the water rise?

– Yes, because it isn’t heavy.

– Which is heavier, this little stone or this big piece of wood?

– The stone (correct).

– Then what makes the water rise higher?

– The wood.

– Why?

– Because it’s bigger.

– Then why did the stones make the water rise?

– Because they are heavier.

Here we see how easily the child discards one feature (weight) which in his opinion made the water rise, and replaces it with another (size). Each time his conclusions are arrived at in a case-by-case manner, and he is quite unaware of the lack of a single explanation. This, brings us to another interesting fact about children: as far as they are concerned, contradictions do not exist. Diametrically opposed opinions may exist side by side without excluding each other.

A child may assert that in one case the water is displaced by an object because it is heavy, and in another because it is light; or that boats float on the water because they are light, but steamers do so because they are heavy – without feeling that any contradiction is involved.

Here is complete transcript of one such conversation. [21]

Child T. (7 1/2 years).

– Why does wood float on water?

– Because it’s light and because boats have oars.

– What about boats that don’t have oars?

– It’s because they're light.

– And what about big steamers?

– It’s because they're heavy.

– Does that mean that heavy things stay on top of the water? – No.

– What about the big stone?

– It sinks.

– And the big steamer?

– It floats because it’s heavy.

– Just because of that?

– No, also because it has big oars.

– What if we take them away?

– It will get light.

– And what happens if we put them back?

– It will stay on top of the water, because they're heavy.

The child’s total indifference to contradictions is well illustrated by this example. Each time, he draws conclusions from case to case. The child does not feel trapped by their mutually contradictory nature, because he has yet to learn the laws of logic elaborated by culture, which are rooted in the objective experience of man, in collisions with reality and in the verification of one’s premises. For that reason, it is supremely difficult to trap a child by pointing out the contradictory nature of his conclusions. The above-mentioned characteristics of the thinking of the child, and the exceptional ease with which it uses inferences from one particular case to draw conclusions in another, without pondering the real relationships involved, enable us to observe in the child certain small samples of thinking which are found occasionally and in specific forms only in adult primitives.

On encountering the phenomena of the external world, the child inevitably begins to construct his own hypotheses about the causes of individual things and the relationship between them; those hypotheses must inevitably assume primitive forms consonant with the peculiarities of the thinking of the child. Being accustomed to using inferences from one particular case to draw conclusions in another, the child, when constructing hypotheses concerning the external, tends to connect things at random. The child still knows nothing of the impediments to causative dependence that really exist and that become self-evident to the civilized adult only after lengthy knowledge of the external world. In the child’s representation, one thing may act upon another independently of distance and time, and even when they are totally unconnected. It is possible that the nature of these representations may be rooted in the child’s egocentric disposition. It is worth recalling, in this regard, how the child, while still limited in his ability to tell the difference between reality and fantasy, achieves the illusory satisfaction of his desires whenever they are thwarted by reality.

This attitude to the world gradually leads to the formation in the child’s mind of a primitive representation to the effect that it is also possible in nature for any one thing to be connected to any other, or to act, by itself, upon any other. We became particularly convinced of this primitive and naive-psychological character of the child’s thinking after a series of experiments which were recently conducted, simultaneously, in Switzerland by Piaget, and in Germany by the psychologist Carla Raspe.[22]

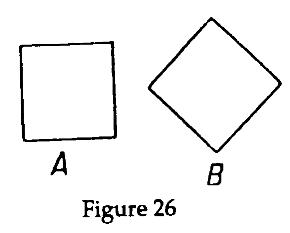

In her experiments, a child was presented with an object which for various reasons changed its shape after a certain time. It could, for example, be a figure which, under certain conditions, would create an illusion; or a figure which, when placed against a different background, began to seem bigger; or a square which, when turned on end (Figure 26), would create the illusion of magnification. While this illusion was being presented to the child, an extraneous stimulant was deliberately added: for example, an electric light or a metronome, was turned on. Then, when the experimenter asked the child to explain the reason for the illusion, or say why the square had grown bigger, the child invariably referred to the new, simultaneously acting stimulant as the reason. He would say that the square grew bigger because a light came on or the metronome started ticking, although there was, of course, no evident connection between these phenomena.

The child’s confidence in the connection between these phenomena, like his post hoc ergo propter hoc logic, was so great that if we ask him to alter the given phenomenon, and to make the square smaller, he would go without a moment’s thought to the metronome and stop it.

We sought to reproduce these experiments in our laboratory, and invariably reached the same results with children aged 7-8.

Only a very few of them proved capable of restraining the urge to make the standard answer, to construct some other hypothesis or admit their ignorance. Far more children demonstrated even more primitive traits of thinking, by actually saying that these simultaneously occurring phenomena were also connected by a causative link. Simultaneously means consequentially: this is one of the basic premises of the thinking of the child. One can well imagine the kind of picture of the world that such primitive logic creates.

It is interesting to note that the same primitive traits are still present in the judgments of older children, as confirmed by the figures supplied to us by Raspe: out of ten ten year olds studied, eight said that the figure grew bigger because the metronome had been turned on, one constructed a different theory, and only one refused to offer an explanation.

This “magical thinking” mechanism is most vividly manifested in children aged 3-4. From their reactions, one can instantly see how a purely external assessment of some phenomenon induces the child to arrive at a hasty conclusion about its role. A girl who had been observed by one of us remarked that the small errands that her mother gave her were successful when the mother repeated. two or three times what she had to do. After this had happened a number of times, the following event was observed: once, when the girl was sent into another room on a minor errand, she asked her mother to repeat it three times, but then promptly ran off into the next room without waiting to hear. Her primitive, naive attitude to her mother’s words is quite evident, and needs no further explanation.

Such is the general picture of the child’s thinking before he has begun to ascend the ladder of cultural influence, or while he is still only on its lower rungs.

As the child begins his career as an “organic creature”, he remains closed in and egocentric; protracted cultural development is needed in order for his first tenuous link with the world to be strengthened, and for the orderly structure we call the thinking of civilized man to develop instead of the primitive thinking of the child.