Background to the Middle East Crisis, Part One: Zionism, International Socialism (1st series), No.64, December 1973, pp.15-21.

Transcribed by Mike Pearn.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

Last month this journal said: “The fight of the Arab armies against Israel is a fight against western imperialism ... there is only one way to real peace in the Middle East and that is through the destruction of the Zionist state, with its preferential citizenship rights along racial lines, and its replacement by a Palestinian state, in which Jews and Arabs have equal rights.”

This is a conclusion rejected by many people who consider themselves on the left. In recent weeks the official Labour party line – mouthed by such “left wingers” as Eric Heffer – has been even more rabidly pro-Israel than the Tory press. Others who would normally feel in close agreement with the revolutionary left find themselves confused as to why we take the position that we do.

One of the truly great propaganda exercises of our time has sold the Zionists’ pretensions to legitimacy in the Middle East. Israel has presented itself as the tiny victim of Arab intransigence, explaining its aggression and expansionism as a life or death pre-emptive strike. Zionism is equated with Jewishness and justified as the sole bastion against anti-semitism.

In almost every respect the propaganda pretensions of Zionism cannot stand even a cursory examination.

The first pervasive myth is that of its continuity with historical Jewry. It is claimed that Palestine has been the historic home of the Jews, from which they have been forcibly excluded and which they have some intrinsic right to inhabit, even at the expense of those who have lived there since.

But even the most ardent Zionists admit that the vast majority of the Jews have not lived in Palestine since the destruction of Jerusalem in 60 AD. And well before that most Jews lived not in Palestine, but throughout the Greek and Roman world. “The dispersal of the Jews does not date from the fall of Jerusalem. Several centuries before this event, the great majority of Jews were already spread over the four corners of the world. It is quite certain that well before the fall of Jerusalem, more than three-quarters of the Jews no longer lived in Palestine,” wrote Leon. [1]

For more than 1800 years successive generations of Jews, moving from country to country, did not consider returning to the land now claimed to be their natural home. Not until the closing years of the nineteenth century did a few thousand Jews begin to argue that because there was no possibility of fighting anti-semitism in Europe, it was necessary for the Jews to establish a state of their own. And even then, so weak were the alleged links between the Jews and Palestine that Herzl, who wrote the founding Zionist document, The Jewish State, considered Palestine as only one of several possible sites – including Argentina, Uganda and – interestingly enough – parts of Sinai.

As late as 1914, only 130,000 out of a world Jewish population of 13 million backed the Zionist programme of a return to Palestine. [2]

In 1882 the Jewish population of Palestine numbered only 23,000 – most of whom had lived on friendly terms with the Christian and Muslim population for hundreds of years and were hardly distinguishable from them. However, the French Baron de Rothschild had already built some 20 villages in which he settled 5,000 east European Jews, aiming to begin colonising the land in the interests of French imperialism, in the same way that Algeria was colonised.

But modern Zionism was not born until a congress held in Basle, Switzerland, in 1897. From the very beginning the movement and its leaders were clear that they must attach themselves to a leading power to achieve a Jewish state. They knew there was no other way to protect themselves from the wrath of the Arab population they aimed to displace. Zionism could only flourish by aligning itself with the forces that wanted to dominate and exploit the rest of the Middle East.

As Herzl’s deputy, Max Nordau, formulated Zionist foreign policy: “Our aspirations point to Palestine as a compass points north, therefore we must orient ourselves towards those powers under whose influence Palestine happens to be.” [3]

In this quest for client status, Herzl made unsuccessful approaches to the German Kaiser and the Turkish Sultan. In 1906, two years after Herzl’s death, Weitzman, his successor, had the first meeting with Balfour, a meeting that some 11 years later was to bear fruit in the Balfour declaration, which promised a “Jewish Homeland”. Balfour, incidentally, was head of the British Tory Government which pushed through in 1905 an Aliens Act deliberately designed to curtail the entry of East European Jewish refugees into Britain.

From the beginning, Weitzman made clear to the British his willingness to act on behalf of British interests. In a letter to Lloyd George in November 1914 he wrote: “We can reasonably say that should Palestine fall within the British sphere of influence and should Britain encourage Jewish settlement there, as a British dependency, we would have in 20 or 30 years a million Jews, perhaps more; they could develop the country, bring back civilisation and form a very effective guard for the Suez canal.”

It must have been a matter of some satisfaction for Weitzman at the end of his life that all the predictions of this short paragraph eventually came true.

The Balfour Declaration was published in 1917. Although hedged with reservations on the cultural and political rights of the Arab Palestinians, it made clear the British government’s approval of “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”, and went on to promise the government’s “best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object.” Britain, of course, was disposing of war gains not yet made at the expense of the unconsulted and unconsidered Palestinians.

At the end of the First World War the British divided up the area with the French, giving the French the Lebanon and Syria, and taking Iraq, Palestine and Transjordan for themselves. They already ran Egypt.

The Zionists began to set up their shadow state protected by British power. The Zionist parties were subsidised by foreign funds funnelled through the Jewish Agency.

The case of the Histadrut is an example of the massive aid that supported the Zionist presence. The Histadrut the General Confederation of Jewish Workers in the Land of Israel, started in 1920 with only 5,000 members, strictly limited to Jews. Within a year it had a large public works company and a bank. Today Histadrut companies account for 25 percent of net national product and employs a quarter of Israeli workers. It builds roads and military installations in Turkey and luxury hotels in emerging African countries.

These developments were not financed by the subscriptions from the 5,000 Jewish workers but by money collected in Europe and America by the Jewish Agency and the World Zionist Organisation. As Pinhas Lavon, general secretary of Histadrut, said: “Our Histadrut is a general organisation to the core. It is not a workers’ trade union although it copes perfectly well with the real needs of the worker.” [4]

Besides being true, this revealing statement would not be out of place in the mouth of a functionary of one of Franco’s fascist syndicates.

On such a basis, the Zionist settlements were able to expand: by 1931 the percentage of Jews in the total population was nearly 18 percent and by 1939 it had risen to nearly one third. [5]

The benefits the British gained from the Zionist colonisation were shown in 1936, when a general strike was declared against French rule in Syria. It proved effective and on the whole successful, taking Syria well along the road towards political independence. This made a great impression in Palestine, where the Arab population began an uprising against British rule, together with a long general strike of its own. The effects of the strike, however, were dampened by the Zionist presence. The institutions run by the Jewish settlers took no part in the strike and took over many of the functions previously performed by the Arabs.

The armed rising tied down more than a third of the British Army’s total world wide strength, and the British authorities again looked to the Zionists for support. The mandatory government agreed to reinforce the Jewish police force in order to free British soldiers for guard duty, and it established the Jewish Settlement Police, which became the main camouflage of the Haganah, the Zionist secret army. In the spring of 1939 the combined Jewish auxiliary police forces numbered about 21,000 men. [6]

In the wake of the rebellion, the British sent out a Royal Commission under Lord Peel to discover the causes of Arab unrest. Its conclusion was that the mandate was unworkable and recommended partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. This ominous prelude to 1948 was accepted by the Zionist leaders, Ben Gurion and Weitzman. At the 21st Zionist congress in 1939 they declared: “The Jewish people will not acquiesce in the reduction of its status in Palestine to that of a minority, nor in the subjection of a Jewish National Home to Arab rule.” Never mind the fact that they were a minority in an Arab country.

By the beginning of the war, the Zionists recognised that Britain was in decline and that a more powerful star was in the ascendant, the United States. The Americans, who were trying to displace British influence in areas such as Saudi Arabia, were not slow to see the advantages of an alliance with the Zionists.

When Britain, as a sop to the Arabs, put quotas on Jewish immigration for five years, Roosevelt commented: “... it (the Palestinian mandate) did intend to convert Palestine into a Jewish home which might very possibly become preponderantly Jewish within a comparatively short time ...” [7]

There can be no doubt that liberal opinion was shocked at the restriction on Jewish immigration. At the time the Nazi extermination of the Jews was in full swing. Such shock would have been considerably tempered if it had been generally known that at the Bermuda Committee in 1943 Roosevelt suggested that all barriers be lifted for the immigration of Jews from persecution. To avoid offending British sensibilities, Palestine was excluded from consideration. Zionist reaction was immediate and hostile for the Zionists the alleviation of Jewish misery was to be via Palestine or not at all.

Hal Draper records that “Morris Ernst, the famous civil liberties lawyer, has told the story about how the Zionist leaders exerted their influence to make sure that the US did not open up immigration (into the US) to these Jews – for the simple reason that they wanted to herd these Jews to Palestine.” [8]

As Dr Silver told the 22nd World Zionist Congress: “Zionism is not an immigration or refugee movement, but a movement to re-establish the Jewish state for a Jewish nation in the land of Israel. The classic textbook of Zionism is not how to find a home for refugees. The classic textbook of our movement is the Jewish state.”

At the end of the war, the Zionists called for partition and were backed by America. Meanwhile, they began a terror campaign against the British troops – not designed to liberate Palestine from imperialist rule, but rather “to demonstrate to the British military authorities that without the goodwill of Palestine Jewry, the British troops in Palestine might be dangerously isolated.” [9]

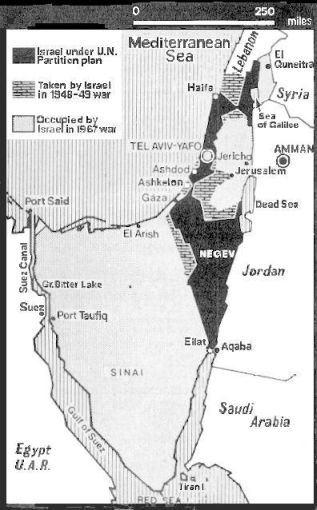

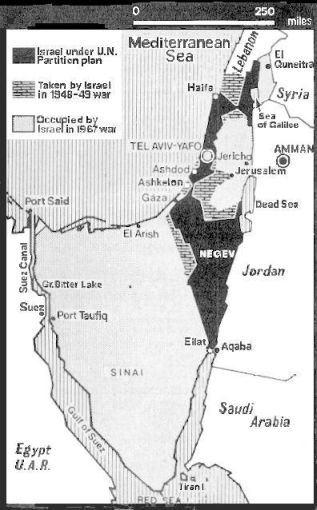

When at the end of 1947 Britain finally announced its imminent withdrawal from Palestine, there were 1,203, 000 Arabs in the country, accounting for two-thirds of the population. 94 percent of the land was owned or settled by Arabs. The remaining 6 percent was Jewish owned and 85 percent of these Jews had immigrated since 1922. [10] But the Zionists were determined to extend their area of control. In November 1947 Golda Meir met secretly with Abdullah, the British imposed ruler of Jordan, and they agreed to divide the territory of the Palestinians between them. [11]

In 1942 Weitzman had written: “... if any Arabs do not wish to remain in a Jewish state, every facility will be given to them to transfer to one of the many and vast Arab countries.” He had the good grace not to specify what facilities would be made available.

Mehachem Beigin, commander of the more extreme Zionist armed force, Irgun Zwei Leumi, was clear that the facilities would include guns, bombs, murder and extermination. He later said: “Our hope lay in gaining control of territory. At the end of January 1948 ... we outlined four strategic objectives: 1. Jerusalem, 2. Jaffa, 3. The Lydda, Ramleh Plain, 4. The Nablus, Jenin, Tulkarm triangle.” All these towns were part of the Arab territory under the United Nations partition plan sponsored by the Zionists.

In April, the Irgun bombed the Arab town of Jaffa for three days. Haganah attacked the Arab community in Jerusalem. On 9 April the Irgun, in concert with the extreme Zionist Stern gang, which in the 1930s received training in Fascist Italy, attacked the Arab village of Dair Yassin and, in cold blood, murdered 254 women and children. Menachem Beigin and Avram Stern had learned well Hitler’s lesson in genocide. The news of the massacres and bombing set in motion the Palestinian refugees, some fleeing as far as the east bank of the river Jordan to escape the Zionists.

By these tactics the Zionist forces were able to increase their share of the partitioned state by 25 per cent before the UN resolution had been passed.

The first Arab-Israeli war of May 1948 was not, as Israeli propaganda would have us believe, an unprovoked Arab aggression. It was a response to the moving of Zionist forces into Arab Palestine. As the Zionists and Abdullah moved into areas inhabited by the Palestinians, Egypt and Saudi Arabia intervened – more out of fear of Abdullah than anything else.

If further proof is required, it should be noted that the only Arab army actually to invade the Jewish part of Palestine was that of the Egyptians, who sent a small force from Sinai into the Negev. All the other armies fought on Arab soil.

In the aftermath of the armistice the Zionists’ spoils of victory and additional territory were quickly recognised by all the great powers. The partition plan was dead and Israel was born on the corpses and the land of the Palestinians.

Having expelled the Arabs by force, the Zionists went on to set a legal seal on the expropriation of Arab property.

Even before the formal setting up of the state of Israel, the Jewish Agency appointed a Haganah officer to act as Custodian of Arab Property. Once it was set up, emergency legislation on 24 June 1948 set out the Abandoned Areas Ordinance. An abandoned areas was: “... any area or place conquered by or surrendered to armed forces or deserted by all or part of its inhabitants, and which has been declared by order to be an abandoned area.” This definition, which could have covered any land anywhere, Jewish or Arab owned, applied only to Arab land.

A category of Arab known as “absentee” was invented. This included not only those who had left but those who had merely left their homes to avoid the fighting. As Don Peretz, a non-Zionist but pro-Israeli author, wrote in his book Israel and the Arab Refugees:

Any Arab of Nazareth who might have visited the Old City of Jerusalem or Bethlehem on Christmas 1948, automatically became an “absentee” under the law. Nearly all the Arab refugees in Israel as well as the 30,000 inhabitants of the little Triangle, which become part of the state under the armistice with Jordan, were classified as absentees. Arabs, who during the battle of Acre, fled from their homes to the old city of Acre, lost their property ... All of the new city of Acre was turned over to the recent (Jewish) immigrants despite the fact that many of its Arab “absentee” home owners were living a few yards away ...

Arabs were “absentees” unless they could prove they were not.

In 1953 a new twist was added to the Land Acquisition law. The crux of this law was that land would become the property of the Development Authority if:

1. On 1 April 1952, it was not in the possession of its owners.

2. It was used or earmarked within the period 4 May 1948 to April 1952 for the purposes of essential development or security.

3. If it is still required for one of these purposes ...

The outstanding gall of the first of these meant that those who had been illegally thrown off their land could not have been in possession at 1 April 1952. That was their complaint. Catch 22 is alive, and well, and living in Israel.

An amendment was passed which made it possible for legal Arab residents to keep any property they might obtain in the future. As one commentator said: “They were not to be robbed of any property which they do not yet possess.” [12]

In this way, the Israeli government acquired practically all the available Arab land for Jewish settlement. Over one million dunams (i.e. 250,000 acres) were taken from the Arabs who did not flee from Israel under the land acquisition law. [13]

All told 4,574,000 dunams of cultivatable land were taken from the Arabs, out of a total area under cultivation of about six million dunams. [14]

Since 1967, the expansion of the area of Zionist colonisation has continued. Kibbutzim – which are effectively military fortifications – have been established in the occupied areas. A document recently produced by the Israeli Labour Party “makes it clear that Israel will continue to establish and develop new settlements in the occupied territories ... The policy document makes it clear that the Israeli land Authority will acquire land in the occupied area by every effective means.” [15]

Israel’s pose as a democratic beacon in the Middle East, a custodian of western liberal values, does not stand examination when the position of the Palestinians who remain inside Israel (let alone the millions and more who were driven out) is examined. Under Israeli law, a Palestinian may be limited in his movements merely by the say so of a military officer. There are cases of individuals who have been refused permission to leave their villages for as long as 20 years. [16] but these are fortunate compared to those who are held in prison without trial. “The Israeli preventative detention law permits the imprisonment – without limit of time – of ‘any person’ whose confinement is deemed ‘necessary or expedient’.” [17]

The situation for the inhabitants of the West Bank of the Jordan and the Gaza strip is even worse. Although these areas have been effectively integrated into the Israeli economy, with 60,000 Arabs travelling to work inside Israel proper, the wages paid are 40 to 50 percent less than the wages paid to Israelis. [18]

Since it was occupied in 1967, the Gaza Strip has been turned into one massive festering prison. The refugees are flung out and their huts razed to the ground to build roads the better to police the area. In 1970 the Gazans spent 3700 hours under curfew. [19] In 1971 the Israelis started a plan to move tens of thousands of Palestinians from Gaza to Sinai, presumably intending to hand them over to Egypt at some future peace conference. The Israeli army moved into Jebalia, second largest camp in Gaza, (40,000 refugees) and it proceeded to bulldoze the huts and transport the inhabitants who had not fled to Al Arish in Sinai.

|

The rulers of Israel faced two problems after 1948. The first was developing the country so as to make it an attractive proposition to the hundreds of thousands of European Jews it wanted to attract as immigrants – people who are used to a European rather than a Middle Eastern standard of living. The second problem was to persuade the neighbouring Arab states to accept the vastly expanded frontiers of Israel and the permanent expropriation of the previous Palestinian inhabitants. They sought to solve both problems by proving that they were imperialism’s best friend in the area.

The talk of “making the desert bloom” is a bit less impressive when you look at the amount of aid Israel has received – particularly from America. Oscar Gass, an American economist who at one time acted as advisor to the Israeli government, has noted:

What is unique ... about this development ... is the factor of capital inflow ...During the 17 years 1949-65 Israel received six billion dollars more of goods and services than she exported. For the 21 years 1948-68 the import surplus would be in excess of seven and a half billion dollars. This is in excess of 2650 dollars per person for every person who lived in Israel. And of this supply from abroad ... only about 30 per cent came to Israel under conditions which call for a return outflow of dividends, interest or capital. [20]

It has been calculated that in 1968, Israel received more than 10 per cent of the total aid given to all underdeveloped countries. [21]

Only through this inflow of funds was the development of the Israeli economy possible. Despite the talk of “hardworking pioneers”, between 1949 and 1965 the net saving if the Israeli economy equalled zero, sometimes being +1 per cent and sometimes -1 per cent. Yet the rate of investment over the same period could average 20 per cent. [22]

In the light of such generosity from foreign sources it is hardly surprising that one or two parcels of the Negev have nurtured the odd rose.

It is true that much of this inflow of funds has come from collections from world Jewry, rather than from Western governments (which accounted for about 40 per cent of capital transfers in the period 1949-65); but it is also true that the very rich Jewish families in the US who have contributed such a large chunk of these funds would not have done so unless Israel was following a policy favourable to the class to which they belong – the American capitalist class.

A major plank of the governmental policy of the Israeli state has always been to secure recognition for the annexation of the Palestinian areas obtained in 1948. The first formal recognition came from the three western powers with imperialist interests in the area, Britain, France and the US, with the Tripartite Declaration of 1950. Since then the main Israeli aim has been to force the Arab states to concede similar recognition.

In the early 1950s, the US and Britain wanted to create a military alliance of Middle Eastern countries, as part of the global policy of establishing a chain of bases and military pacts around Russia. The Israeli leaders exerted themselves to help force the Arabs into the alliance. Whenever the governments of Egypt, Syria or Jordan attacked the Anglo-American schemes, Israel was used as a threat against them. These threats often materialised in armed raids by Israeli forces. Jordan, particularly, was raided during the period when the el-Nabulsi government there conducted anti-Western policies. Usually after such a raid, the Arab government concerned would ask the West for arms. The reply was always “Join the Bagdad Pact and you will get the arms.”

The policy was finally defeated when, after an Israeli raid on Gaza in April 1955 Nasser turned to the Russian bloc for arms. This development, followed by the nationalisation of the Suez Canal, drove Britain and France into desperation. Together with Israel they attacked Egypt in an attempt to seize back the canal for the Western shareholders and re-establish their own influence. [23]

The third Arab-Israeli war of 1967 was preceded by a similar period of rising struggle against British rule in Aden; the struggle against the Iman of Yemen represented a potential threat to the Saudi-Arabian monarchy; and the Syrian government was involved in a dispute with the US dominated Iraq Petroleum Company.

In the aftermath of the Israeli victory, the Western presence in the area was considerably strengthened. As the Economist out it at the time: “It is not only Israel’s chestnuts which have been drawn out of the fire; it is those of Britain and America as well ...” [24]

In recent years, the American government has been following a policy of guarding its interests in the Middle East by massively arming the most reactionary regimes. Israeli power on the Mediterranean coast has been matched by a massive military build-up in Iran (which now sends more than 2000 million dollars a year on arms) and a growing sale of arms to Saudi Arabia and the small states on the Persian Gulf. In this way, the US aim to have sufficient forces at its disposal to prevent the massively rich oil reserves in the Arabian peninsular – currently under the control of US oil companies – falling under the influence of the larger and more populous Arab states such as Iraq or Egypt, which might use some of the wealth for Arab ends. So for instance, when Iran agreed earlier this year t spend 2000 million dollars on the most modern US armaments, the US State Department observed that the deal would help reinforce “a point of stability” in the Gulf area. [25] The Shah of Iran has said quite openly that “he would not tolerate a radical or subversive presence in the Gulf”. [26]

What stability means for the mass of the population in the Middle East is an accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few rulers, while the population of countries like Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Jordan live in abject poverty. The Oil Minister of Saudi Arabia recently complained that for his country oil revenues which are expected to rise to 10,000 million dollars a year, “would constitute a serious problem”. [27]

The arming of Israel and Iran is designed to ensure that this “problem” is not solved by a movement aiming to overthrow the reactionary monarchies and to use the oil to develop the whole Middle East for the benefit of the mass of the Arab population.

The editor of the Israeli daily paper Ha’aretz summed up Israel’s role in all this quite succinctly in 1951: “Israel has been given a role not unlike a watchdog. One need not fear that it will exercise an aggressive policy towards the Arab states if this will contradict the interests of the USA and Britain. But should the West prefer for one reason or another to close its eyes one can rely on Israel to punish severely those of the neighbouring states whose lack of manners towards the West has exceeded the proper limits.” [28]

The support of Israel for imperialism is not an accidental feature of the state, that could be overcome merely with a change of government. It follows necessarily from the attempt to establish an exclusively Jewish state in an area previously inhabited by non-Jews. To defend the settler state from the original inhabitants, an alliance with the imperialist exploiters of the Middle East has been, and remains, essential.

There can be no question of socialists supporting Israel. There is no justification for saying a plague on both your houses. In face of Zionism and its paymaster, socialists must give unconditional, if critical support to the Arabs. Israel, the artificial creation of Zionism, has to be destroyed before the working masses of the Middle East, Muslims, Jews and Christians have a chance to live together in peace. The very existence of Israel is the denial of any peace.

1. A. Leon, The Jewish Question, p.30.

2. J.M.N. Jeffries, Palestine, The Reality, p.13.

3. Quoted by N. Israeli, Israel and Imperialism, IS 32.

4. Moed, published by the department of culture and education of the Histadrut, 1960, p.3.

5. M. Arakie, The Broken Sword of Justice, p.17.

6. Y. Bauer, in New Outlook, Tel Aviv, September 1966.

7. Arakie, op. cit., p.25.

8. New Politics, vol.6 no.1, p.16.

9. J. and D. Kimche , Both Sides of the Hill, p.53.

10. Arakie, op. cit., p.70.

11. For an account of the joint manoeuvrings of Abdullah and the Zionists see J. and D. Kimche, op cit.

12. Hal Draper in the New International, Winter 1957.

13. Ha’aretz, 7 January 1954.

14. Don Peretz, Israel and the Arab Refugees, p.233.

15. Economist Intelligence Unit, Quarterly Report, Israel, 1973 No.4.

16. Report of Israeli League for Human and Civil Rights, distributed in August 1973.

17. A. Dershowitz, in I. Howe and Chersham (ed), Israel, the Arabs, and the Middle East, New York 1972, p.268.

18. Wage figures for Arabs given in Financial Times, 7 May 1973.

19. Guardian, 18 August 1971.

20. Journal of Economic Literature, December 1969. Quoted in H. Hanegbi, Machover and A. Orr, The Class Nature of Israeli Society, (published by Pluto Press, London).

21. Le Monde, 2 July 1969.

22. Figures from N. Halevi and R. Klinov-Malul, The Economic Development of Israel, quoted in N. Hangebi et al., op. cit.

23. The preceding two paragraphs are based on Theses submitted for discussion by the Israeli Socialist Organisation in August 1966, published as The Palestine Problem, Israel and Imperialism, New England Free Press, Boston.

24. The Economist, 10 June 1967.

25. Middle East Economic Digest, 3 March 1973.

26. Economist, 7 July 1973.

27. Middle East Economic Digest, 19 January 1973.

28. Quoted in H. Hanegbi et al., op. cit.

Last updated on 19.10.2006