William Z. Foster

The Great Steel Strike and Its Lessons

THE WHITE TERROR—CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS DENIED—UNBREAKABLE SOLIDARITY—FATHER KAZINCY—THE COSSACKS —SCIENTIFIC BARBARITY—PROSTITUTED COURTS—SERVANTS REWARDED

It was the misfortune of the steel strike to occur in the midst of the post-war reaction, which still persists unabated, and which constitutes the most shameful page in American history. Ours are days when the organized employers, inspired by a horrible fear of the onward sweep of revolution in Europe and the irresistible advance of the labor movement in this country, are robbing the people overnight of their most precious rights, the fruits of a thousand years of struggle. And the people, not yet recovered from war hysteria and misled by a corrupt press, cannot perceive the outrage. They even glory in their degradation. Free speech, free press, free assembly, as we once knew these rights, are now things of the past. What poor rudiments of them remain depend upon the whims of a Burleson, or the rowdy element of the American Legion. Hundreds of idealists, guilty of nothing more than a temperate expression of their honest views, languish in prison serving sentences so atrocious as to shock the world—although Europe has long since released its war and political prisoners. Working class newspapers are raided, denied the use of the mails and suppressed. Meetings are broken up by Chamber of Commerce mobs or thugs in public office. The right of asylum is gone—the infamous Palmer is deporting hundreds who dare to hold views different from his. The right of the workers to organize is being systematically curtailed; and crowning shame of all, workingmen can no longer have legislative representatives of their own choosing. In a word, America, from being the most forward-looking, liberty-loving country in the world, has in two short years become one of the most reactionary. We in this country are patiently enduring tyranny that would not be tolerated in England, France, Italy, Russia or Germany. Our great war leaders promised us the New Freedom; they have given us the White Terror.

Realizing full well the reactionary spirit of the times, the steel companies proceeded safely to extremes to crush the steel strike, dubbed by them an attempt at violent revolution. To accomplish their end they stuck at nothing. One of their most persistent and determined efforts was to deprive the steel workers of their supposedly inalienable right to meet and talk together. Throughout the strike, whenever and wherever they could find municipal or court officials willing to do their bidding, the steel barons abolished the rights of free speech and free assembly, so precious to strikers. Few districts escaped this evil, but as usual, Pennsylvania felt the blow earliest and heaviest. Hardly had the strike started when the oily Schwab prohibited meetings in Bethlehem; the Allegheny and West Penn Steel Companies did the same at Natrona, jailing organizer J. McCaig for “inciting to riot”; in the Sharon-Farrell district the steel workers, denied their constitutional rights in their home towns, had to march several miles over into Ohio (America they called it) in order to hold their meetings.

Along the Monongahela river the shut-down was complete. Following Sheriff Haddock’s proclamation and the “riots” at Clairton and Glassport, it was only a few days until the city and borough officials had completely banned strike meetings in all the territory from Charleroi to Pittsburgh. The unions’ free-speech, free-assembly victory of the past summer was instantly cancelled. For forty-one miles through the heart of America’s steel industry, including the important centers of Monessen, Donora, Clairton, Wilson, Glassport, McKeesport, Duquesne, Homestead, Braddock, Rankin, etc., not a meeting of the steel workers could be held. Even in Pittsburgh itself meetings were prohibited everywhere except in Labor Temple. The steel-collared city officials never could quite muster the gall to close Labor’s own building—or perhaps because it is so far from the mills and so poorly situated for meetings they felt it to be of no use to the strikers. Thus the Steel Trust gave its workers a practical demonstration of what is meant by the phrase, “making the world safe for democracy.”

Not only were mass meetings forbidden, but so also were regular business meetings under the charters of the local unions. To test out this particular usurpation, Attorney W. H. Rubin, then in charge of the strike’s legal department and possessed of a keener faith in Pennsylvania justice than the Strike committee had, keener probably than he himself now has, prayed the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas to enjoin Mayor Babcock and other city officials from interfering with a local union of the Amalgamated Association holding its business meetings on the south side of the city where its members lived and where several large mills are located. At the hearing the Mayor and Chief of Police freely admitted that there had been no violence in the strike, and even complimented the men on their behavior, but they feared there might be trouble and so forbade the meetings. The honorable Judges Ford and Shafer agreed with them and denied the writ, saying among other things:

It is the duty of the Mayor and Police Department to preserve the peace, and it must be sometimes necessary for that purpose to prevent the congregating in one place of large numbers of people such as might get beyond the control of the Police Department, and it must be left to the reasonable discretion of the officers charged with keeping the peace when such intervention is made.

In other words, the sacred right of the workers to meet together depends upon the arbitrary will of any politician who may get into the office controlling the permits. Shortly before Judges Ford and Shafer handed down this noble conception of free assembly, Judge Kennedy of the Allegheny County Court, ruling on the appeal of Mother Jones, J. L. Beaghen, J. M. Patterson and Wm. Z. Foster in the Duquesne free speech cases of several weeks prior to the strike, had this to say:

It cannot be questioned that the object of these meetings—increasing the membership in the American Federation of Labor—is a perfectly lawful one, but the location of the meetings in the Monongahela valley, built up as it is for mile after mile of an unbroken succession of iron and steel mills, and thickly populated with iron workers, many of whom obviously are not members of this association, and among whom, on both sides, there are, in all probability, some who upon the occasion of meetings such as these purported to be, might through excitement precipitate serious actions of which the consequences could not be foreseen and might be disastrous, presents questions which are sufficient to cause the court to hesitate before interfering with the exercise of discretion on the part of the Mayor in refusing to permit such meetings at this time.

The Court is still hesitating to interfere with Mayor Crawford’s tyranny, and the defendants had to pay $100 and costs each for trying to hold a meeting on ground they had leased. One would think that the remedy in the case conjured out of thin air by the learned judge (for in the thousands of meetings held in the steel campaign he cannot point to one incident of violence) would be for the local authorities to provide ample police protection to insure order. But no, in Pennsylvania the thing to do is to set aside the constitutional rights of the workers. Would such action be taken in the case of members of a Chamber of commerce? Wouldn’t the governor, rather, order out the state troops, if necessary, to uphold their right of assembly?

In the hope of getting some relief, or at the least some publicity about the unbearable situation, a committee of 18 local labor men, representing the largest trade unions in Western Pennsylvania, went to Washington and presented to the Allegheny County congressional delegation a petition expressing contempt for the judges and other officials in their part of the State and asking Congress to give them the justice these men refused to mete out. Surely, the Allegheny County congressmen were exactly the ones to bring the Steel Trust to time. With a grand flourish they introduced a resolution into the House calling for an investigation—then they forgot all about it.

The official tyranny and outlawry along the Monongahela was so bad that the Pennsylvania Federation of Labor had to voice its protest. On November 1-2 it held a special convention in Pittsburgh, attended by several hundred delegates. A resolution was adopted demanding that protection be given the rights of the workers, and that if the authorities failed to extend this protection, “the Executive Council of the Pennsylvania Federation of Labor shall issue a call for a State-wide strike, when in its judgment it is necessary to compel respect for law and the restoration of liberty as guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States and of the State of Pennsylvania.” For this action President Jas. H. Maurer of the Federation was hotly assailed and even menaced with lynching by the lawless business interests.

By some inexplicable mental twist the ex-union man Burgess of Homestead eventually allowed the unions to hold one mass meeting each week—to this day the only ones permitted in the forty-one miles of Monongahela steel towns. They were under the supervision of the State police. At each meeting a half dozen of these Cossacks, in full uniform, would sit upon the platform as censors. Only English could be spoken. As the saying was, all the organizers were permitted to talk about was the weather. When one touched on a vital strike phase a Cossack would yell at him, “Hey, cut that out! You’re through, you—! Don’t ever come back here any more.” And he never could speak there again.

Judging from past experiences the strike in the Pittsburgh district should have been impossible under such hard circumstances. With little or no opportunity to meet for mutual encouragement and enlightenment, the strikers, theoretically, should have been soon discouraged and driven back to work. But they were saved by their matchless solidarity, bred of a deep faith in the justice of their cause. In the black, Cossack-ridden Monongahela towns there were thousands of strikers who were virtually isolated, who never attended a meeting during the entire strike and seldom if ever saw an organizer or read a strike bulletin, yet they fought on doggedly for three and one-half months, buoyed up by a boundless belief in the ultimate success of their supreme effort. Each felt himself bound to stay away from the mills, come weal or come woe, regardless of what the rest did. These were mainly the despised foreigners, of course, but their splendid fighting qualities were a never-ending revelation and inspiration to all connected with the strike.

Through the dark night of oppression a bright beacon of liberty gleamed from Braddock. There the heroic Slavish priest, Reverend Adelbert Kazincy, pastor of St. Michel’s Roman Catholic church, bade defiance to the Steel Trust and all its minions. He threw open his church to the strikers, turned his services into strike meetings, and left nothing undone to make the men hold fast. The striking steel workers came to his church from miles around, Protestants as well as Catholics. The neighboring clergymen who ventured to oppose the strike lost their congregations,—men, women and children flocked to Father Kazincy’s, and all of them stood together, as solid as a brick wall.

Reverend Kazincy’s attitude aroused the bitterest hostility of the steel companies. They did not dare to do him bodily violence, nor to close his church by their customary “legal” methods; but they tried everything else. Unable to get the local bishop to silence him, they threatened finally to strangle his church. To this the doughty priest replied that if they succeeded he would put a monster sign high up on his steeple: “This church destroyed by the Steel Trust,” and he would see that it stayed there. When they tried to foreclose on the church mortgage, he promptly laid the matter before his heterogeneous congregation of strikers, who raised the necessary $1200 before leaving the building and next day brought in several hundred dollars more. Then the companies informed him that after the strike no more Slovaks could get work in the mills. He told them that if they tried this, he would do his level best to pull all the Slovaks out of the district (they are the bulk of the mill forces) and colonize them in the West. The promised blacklist has not yet materialized.

Father Kazincy and the clergymen who worked with him, notable among whom was the Reverend Molnar, a local Slavish Lutheran minister, constituted one of the great mainstays of the strike in their district. They are men who have caught the true spirit of the lowly Nazarene. The memory of their loyal co-operation will long live green in the hearts of the Pittsburgh district steel strikers.

A description of the repressive measures taken by the Steel Trust against its workers during the early period of the strikes necessarily relates almost entirely to Western Pennsylvania. With few exceptions, the other districts were in a deadlock. So tightly were the mills shut down that the companies could hardly stir. It took them several weeks to get their stricken fighting machinery in motion again. But it was different in Western Pennsylvania, in what we call the greater Pittsburgh district; that has always been the key to the whole industry, and there, from the very first, the steel companies made a bitter fight to control the situation and to break the strike. The tactics used there are typical in that they came to be universally applied as the strike grew older, the degree of their application depending upon the amount of control exercised by the Steel Trust in the several localities.

To carry on the terror so well begun by the suppression of free speech and free assembly, the Steel Trust turned loose upon the devoted strikers in Western Pennsylvania the great masses of armed thugs it had been recruiting since long before the strike. These consisted of every imaginable type of armed guard, official and unofficial, except uniformed troops. There were State Constabulary, deputy sheriffs, city police, city detectives, company police, company detectives, private detectives, coal and iron police, ordinary gunmen, armed strike-breakers, vigilantes, and God knows how many others. These legions of reaction, all tarred with the same brush—a servile, mercenary allegiance to the ruthless program of the Steel Trust—vied with each other in working hardships upon the steel workers. In this shameful competition the State Constabulary stood first; for downright villainy and disregard of civil and human rights, these so-called upholders of law and order easily outdistanced all the other plug-uglies assembled by the Steel Trust. They merit our special attention.

The Pennsylvania State Constabulary dates from 1905, when a law was enacted creating the Department of State Police. The force is modelled somewhat along the lines of the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Canadian Northwest Mounted Police. The men are uniformed, mounted, heavily armed and regularly enlisted. For the most part they consist of ex-United States army men. At present they number somewhat less than the amount set by law, 415 officers and men. Their ostensible duty is to patrol the poorly policed rural sections of the state, and this they do when they have nothing else to take up their time. But their real function is to break strikes. They were organized as a result of the failure of the militia to crush the anthracite strike of 1902. Since their inception they have taken an active part in all important industrial disturbances within their jurisdiction. They are the heart’s darlings of Pennsylvania’s great corporations. Labor regards them with an abiding hatred. Says Mr. Jas. H. Maurer (The Cossack, page 3):

The “English Square” is the only open-field military formation of human beings that has ever been known to repulse cavalry. All other formations go down before the resistless rush of plunging beasts mounted by armed men, mad in the fierce excitement induced by the thundering gallop of charging horses. A charge by cavalry is a storm from hell—for men on foot. A cavalry-man’s power, courage and daring are strangely multiplied by the knowledge that he sits astride a swift, strong beast, willing and able to knock down a dozen men in one leap of this terrible rush. Hence, the Cossacks, the mounted militiamen—for crushing unarmed, unmounted groups of men on strike.

But the State Police do not confine themselves merely to the crude business of breaking up so-called strike riots. Their forte is prevention, rather than cure. They aim to so terrorize the people that they will cower in their homes, afraid to go upon the streets to transact necessary business, much less to congregate in crowds. They play unmercifully upon every fear and human weakness. They are skilled, scientific terrorists, such as Czarist Russia never had.

On a thousand occasions they beat, shot, jailed or trampled steel workers under their horses’ hoofs in the manner and under the circumstances best calculated to strike terror to their hearts. In Braddock, for instance, a striker having died of natural causes, about two hundred of his fellows assembled to accompany the body to the cemetery. To stop this harmless demonstration all the State Police needed to do was to send a word to the union. But such orderly, reasonable methods do not serve their studied policy of frightfulness. Therefore, without previously informing the strikers in any way that their funeral party was obnoxious, the Cossacks laid in wait for the procession, and when it reached the heart of town, where all Braddock could get the benefit of the lesson in “Americanism,” they swooped down upon it at full gallop, clubbing the participants and scattering them to the four winds.

Similar outrageous attacks occurred not once, but dozens of times. Let Father Kazincy speak of his experiences:

Braddock, Pa., Sept. 27, 1919

W. Z. Foster,

Pittsburgh, Pa.,Dear Sir:

The pyramidal impudence of the State Constabulary in denying charges of brutal assaults perpetrated by them upon the peaceful citizens of the borough of Braddock prompts me to send a telegram to the Governor of Pennsylvania, in which I have offered to bring forth two specific cases of bestial transgression of their “calling.”

On Monday last at 10 A. M. my congregation, leaving church, was suddenly, without any cause whatever, attacked on the very steps of the Temple of God, by the Constables, and dispersed by the iron-hoofed Huns. Whilst dispersing indignation and a blood frenzy swayed them, a frenzy augmented by that invisible magnetic force, the murmuring, raging force of 3,000 strong men. One could feel that helpless feeling of being lifted up by some invisible force, forced, thrown against the flux of raging, elemental passion of resentment, against the Kozaks of this State.

Nevertheless, it was the most magnificent display of self-control manifested by the attacked ever shown anywhere. They moved on, with heads lowered and jaws firmly set, to submit. Oh, it was great; it was magnificent. They, these husky, muscle-bound Titans of raw force walked home ... only thinking, thinking hard. Oh, only for one wink from some one, would there be a puddle of red horseblood mixed with the human kind.

But no. We want to win the strike. We want to win the confidence of the public.

Tuesday afternoon the little babies of No. 1 were going to the school. They loitered for the school bell to summon them. And here come Kozaks. They see the little innocents standing on the steps of the school-house, their parents on the opposite side of the street. What a splendid occasion to start the “Hunkey’s” ire. Let us charge their babies—that will fetch them to an attack upon us.

They did. But the “Hunkey” even at the supreme test of his cool-headedness, refused to flash his knife to save his babies from the onrush of the cruel horses’ hoofs.

I am relating to you, Mr. Foster, things as they happened. You may use my name in connection with your charges against the Constabulary.

Sincerely yours, Rev. A. Kazincy,

416 Frazier St., Braddock, Pa.

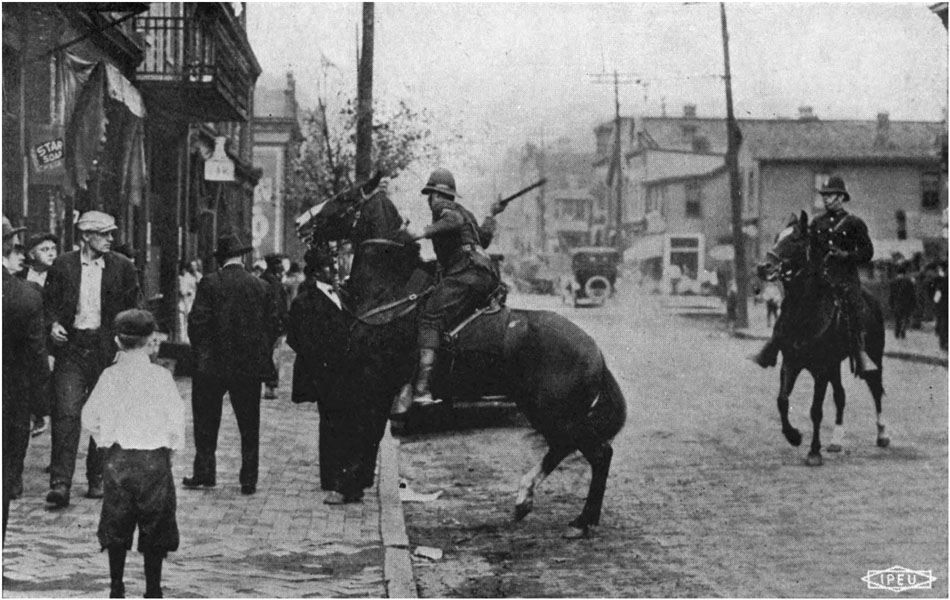

COSSACKS IN ACTION

Brutal and unprovoked assault upon Rudolph Dressel, Homestead, Pa., Sept. 23, 1919.

Photo by International

Governor Sproul paid no attention to Father Kazincy’s protest, nor did he to a long letter from Jas. H. Maurer, reciting shocking brutalities fully authenticated by affidavits—unless it was to multiply his public endorsements and praises of the State Police.

A favorite method of the Constables was to go tearing through the streets (foreign quarter), forcing pedestrians into whatever houses they happened to be passing, regardless of whether or not they lived there. Read these two typical affidavits, portraying a double outrage:

STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA

COUNTY OF ALLEGHENY } SS.Before me, the undersigned authority, personally appeared John Bodnar, who being duly sworn according to law deposes and says that he lives at 542 Gold Way, Homestead, Pa., that on Tuesday, Sept. 23, 1919, at about 2 P. M. he went to visit his cousin on Fifth Avenue, Homestead, Pa.: that he did in fact visit his cousin and after leaving the house of his cousin was accosted on the street by a member of the State Police who commanded him, the deponent, to enter a certain house, which house was not known to the deponent; that deponent informed said State Policeman that he, deponent, did not live in the house indicated by the State Policeman; nevertheless, the said State Policeman said, “It makes no difference whether you live in there or not, you go in there anyhow”; thereupon in fear of violence deponent did enter the said house, which house was two doors away from the house of the cousin of deponent; that after a time deponent came out of the house into which he had been ordered, thereupon the same State Policeman returned and ordered deponent to re-enter the house aforesaid and upon again being informed by deponent that he, the deponent, did not live in said house, the said State Policeman forthwith arrested the deponent and brought him to Homestead police station, and at a hearing at said station before the burgess was fined the sum of nine dollars and sixty-five cents, which amount was paid by deponent.

John Bodnar

Sworn to and subscribed before me

this first day of October, 1919.

A. F. Kaufman, Notary Public.

Here is what happened in the house into which Bodnar was driven:

STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA

COUNTY OF ALLEGHENY } SS.Before me, the undersigned authority, personally appeared Steve Dudash, who being duly sworn according to law deposes and says that he resides at 541 E. 5th Ave., Homestead, Pa.; that on Tuesday September 23, 1919, in the afternoon of said day, his wife, Mary Dudash, was severely scalded, burned, and injured by reason of a sudden fright sustained when a State Policeman forced John Bodnar into the home of the deponent and his wife, Mary Dudash; that said Mary Dudash, the wife of the deponent, was in a very delicate condition at the time of the fright and injury complained of, caused by the State Police and that on Sunday, Sept. 28, 1919, following the date in question, namely the 23rd, the said Mary Dudash, wife of deponent, gave birth to a child; that on account of the action of the State Police in forcing John Bodnar with terror into the home of deponent and his wife, Mary Dudash, she, the said Mary Dudash, wife of the deponent, has been rendered very sick and has suffered a nervous collapse and is still suffering from the nervous shock sustained, on account of the action of the State Police, above referred to.

Steve Dudash

Sworn to and subscribed before me

this first day of October, 1919

A. F. Kaufman, Notary Public

When on a mission of terrorism the first thing the State Troopers do is to get their horses onto the sidewalks, the better to ride down the pedestrians. Unbelievable though it may seem, they actually ride into stores and inner rooms. Picture the horror a foreign worker and his family, already badly frightened, at seeing a mounted policeman crashing into their kitchen. The horses are highly trained. Said an N. E. A. news dispatch, Sept. 26th, 1919:

Horses of the Pennsylvania State Constabulary are trained not to turn aside, as a horse naturally will do, when a person stands in its way, but to ride straight over any one against whom they are directed. Lizzie, a splendid black mare ridden by Trooper John A. Thorp, on duty at Homestead, uses her teeth as well as her heels when in action. Her master will sometimes dismount, leaving Lizzie to hold a striker with her strong jaws, while he takes up the pursuit of others on foot.

If this is thought to be an overdrawn statement, read the following affidavit:

Butler, Pa., October 3, 1919

I, Jacob Sazuta,

21 Bessemer Ave.,

Lyndora, Pa.Commenced work for the Standard Steel Car Company in September, 1913, as laborer. About October 1916 was promoted to car fitter in the erection department; in February, 1919, was then taken and placed as a wheel roller, and I worked in this capacity until August 6th, 1919 [the date the steel strike began there].

On August 25, after receiving my pay, I was standing looking in a store window, when State Trooper No. 52 rode his horse upon me, THE HORSE STEPPING ON MY LEFT FOOT. Trooper No. 52 ordered me to move on, BUT AS THE HORSE WAS STANDING ON MY FOOT I COULD NOT MOVE. He then struck me across the head with his club, cutting a gash in the left side of my head that took the doctor three stitches to close up the wound. After hitting me with his club, he kept chasing me with his horse.

Jacob Sazuta

Sworn and subscribed before me

this third day of October, 1919.

E. L. Cefferi, Notary Public.

A few affidavits, and extracts from affidavits, taken at random from among the hundreds in possession of the National Committee, will indicate the general conditions prevailing in the several districts:

Clairton, Pa.

John Doban, Andy Niski and Mike Hudak were walking home along the street when the State Police came and arrested the three, making ten holes in Mike Hudak’s head. Were under arrest three days. Union bailed them out, $1,000.00 each.

Butler, Pa., Oct. 3, 1919.

I, James Torok,

Storekeeper,

103 Standard Ave.,

Lyndora, Pa.,On about August 15, 1919, I saw State Troopers chase a crippled man who could not run as fast as his horse, and run him down, the horse bumping him in the back with his head, knocked him down. Later three men were coming to my store to buy some things; the State Troopers ran their horses right on them and chased them home. One of the men stopped and said: “I have to go to the store,” and the Trooper said: “Get to hell out of here, you sons — ——, or I will kill you,” and started after them again, and the people ran home and stayed away from the store.

James Torok

Sworn to and subscribed before me

this 3rd day of October, 1919.

E. L. Peffer, Notary Public.

Homestead, Pa.

... two State Policemen made a forcible entry into the home of deponent, Trachn Yenchenke, at 327 Third Ave, Homestead, Pa., and came to the place where deponent was asleep, kicked him and punched him, and handled him with extreme violence and took deponent without any explanation, without permitting deponent to dress, dragged him half naked from his home to waiting automobile and conveyed him against his will to the Homestead Police Station.... Fined $15.10.

Trachn Yenchenke.

Monessen, Pa.

... Concetta Cocchiara, 8 months advanced in a state of pregnancy, was out shopping with her sister. Two State Policemen brusquely ordered them home and when they did not move fast enough to suit, followed them home, forced himself into the house and struck affiant with a stick on the head and grabbed her by the hair and pulled her from the kitchen and forced her into a patrol wagon and took her to the borough jail.... Sworn to before Henry Fusarini, Notary Public, October 11, 1919.

Newcastle, Pa.

John Simpel,

1711 Morris Ave.,

Newcastle.On Sept. 22, about 5.30 P. M. he was walking along towards his home on Moravia Street. Hearing shots fired he stopped in the middle of the street and was instantly struck by bullets three times, one bullet going through his leg, one through his finger, while the third entered his back and went through his body, coming out through his abdomen. The shots were fired from inside the gates of the Carnegie Steel Company’s plant. Mr. Simpel believes the shots were fired from a machine gun, because of their rapid succession. He fell on the ground and lay there for about ten minutes, until he was picked up by a young boy.... He is now totally disabled. He has a wife and a child and is 48 years of age....

Jas. A. Norrington, Secretary.

Farrell, Pa.

... There were four men killed here, one in a quarrel in a boarding house and three by the Cossacks. Half a dozen were wounded, one of them a woman. She was shot in the back by a Cossack, while on her way to the butcher shop....

S. Coates, Secretary.

Many hundreds of similar cases could be cited. In the steel strike a score were killed, almost all on the workers’ side; hundreds were seriously injured, and thousands unjustly jailed. To the State Constabulary attaches the blame for a large share of this tyranny. The effect of their activities was to create a condition in Western Pennsylvania, bordering on a reign of terror. Yet it is extremely difficult to definitely fasten their crimes upon them. No matter how dastardly the outrage, when the Steel Trust cracks its whip the local authorities and leading citizens come forth with a mass of affidavits, “white-washing” the thuggery in question, and usually sufficing to cast serious doubts on the statements of the few worker witnesses courageous enough to raise their voices. What is to be thought of the following incident?

Testifying before the Senate Committee investigating the strike, Mr. Gompers related how, in an organizing campaign in Monessen, Pa. several years ago, A. F. of L. organizer Jefferson D. Pierce was bludgeoned by Steel Trust thugs, receiving injuries that resulted in his death. Mr. Gompers had his facts straight. Yet the very next day, Mr. Gary, testifying before the same Committee, produced a sworn statement from the son of Mr. Pierce containing the following assertions:

I was with my father the night he received his injuries in Monessen, Pa., and wish to state very emphatically that his injury was not caused by any one connected with the United States Steel Corporation. On the contrary, it was caused by a member of the I. W. W. organization from out of town, who was sent there at the time to create trouble, as the I. W. W. organization was then trying to gain control of the organizing situation. I wish again most emphatically to refute Mr. Gompers’ statement that this injury was caused by some one connected with the United States Steel Corporation.

Upon being questioned, Mr. Gary “thought” that Mr. Pierce is employed at Worcester, Mass. by the American Steel and Wire Company, a subsidiary of the U. S. Steel Corporation.

Fortunately, however, in the steel strike the photographer secured a proof of State Police brutality which the most skilled Steel Trust apologists cannot explain away—a picture of the typically vicious assault upon Mr. R. Dressel, a hotel keeper of 532 Dickson St. (foreign quarter), Homestead, Pa. I quote from the latter’s statement in connection therewith:

I, Rudolph Dressel, of the aforesaid address, do hereby make this statement of my own volition and without solicitation from any one. That on the 23rd day of September I was standing in front of my place of business at the aforesaid address and a friend of mine, namely, Adolph Kuehnemund, came to visit and consult me regarding personal matters. As I stood as shown in the picture above mentioned with my friend, the State Constabulary on duty in Homestead came down Dickson St. They had occasion to ride up and down the street several times and finally stopped directly in front of me and demanded that I move on. Before I had time to comply I was struck by the State Policeman. (The attitude of said Policeman is plainly shown in the aforesaid picture, and his threatening club is plainly seen descending towards me.)

My friend and I then entered my place of business and my friend a few minutes afterwards looked out on the street over the summer doors. The policeman immediately charged him and being unable to enter my place of business on horseback, dismounted and entered into my place of business on foot.

My friend being frightened at what had happened to me retired to a room in the rear of my place of business. The Policeman entered this room, accompanied by another State Police, and without cause, reason or excuse, struck my friend and immediately thereafter arrested him. I was personally present at his hearing before Burgess P. H. McGuire of the above city, at which none of the aforesaid policemen were heard or even present. Burgess asked my friend what he was arrested for, and my friend referred to me inasmuch as he himself did not know. The Burgess immediately replied, “We have no time to hear your witnesses,” and thereupon levied a fine of $10.00 and costs upon him. My friend having posted a forfeit of $25.00, the sum of $15.45 was deducted therefrom.

The State Constabulary were sent, unasked for, into the quiet steel towns for the sole purpose of intimidating the strikers. The following took place at the meeting of the Braddock Borough Council, October 6:

Mr. Verosky: (County detective and council member) “Mr. Chairman, the citizens of the borough wish to know by whose authority the State Constabulary was called into Braddock to take up their quarters here and to practically relieve the police of their duties, by patrolling the streets on foot, mounted, and always under arms.”

Mr. Holtzman: (President of Council) “I surely do not know who called them into town, but were I the Burgess, I would make it my business to find out, in view of the fact that the Constabulary is neither wanted nor needed here.”

Mr. Verosky: “Well, in that case, the Burgess may throw some light on the subject.”

Mr. Callahan: (Burgess) “The question comes to me as a surprise and I am sure that I don’t know by whose authority the Constabulary was called in.”

Everything was calm in Braddock until the State Police came in. Then the trouble began. It was the same nearly everywhere. The arrival of these men was always the signal for so-called riots, and wholesale clubbing, shooting and jailing of strikers.

Great praise has been poured upon the State Constabulary for their supposedly wonderful bravery and efficiency, because a few hundred of them, scattered thinly through a score of towns, have been able apparently to overawe many thousands of strikers. But the credit is undeserved. In strikes they always form, in point of actual weight, an insignificant part of the armed forces arrayed against the strikers. For instance, in a steel town, during the strike, there would usually be a dozen or so State Police and from 3,000 to 4,000 deputy sheriffs, company police, etc. The latter classes of gunmen make up the body of the real repressive force; the State Police are merely raiders. It is their particularly dirty job to harass the enemy; to break the strike by scientifically bulldozing the strikers in their homes and on the streets. Thus they are thrown into the limelight, while the company thugs remain in comparative obscurity.

The State Police feel reasonably sure of their skins when carrying on their calculated campaigns of terrorism, for behind them are large numbers of armed guards of various sorts ready to spring to their support at an instant’s notice, should the workers dare to resist them. Besides, they know they have carte blanche to commit the greatest excesses, since the highest state officials, not to speak of local courts and other authorities, give them undivided support. They are above the law, when the rights of the workers are concerned. Moreover, they realize fully that they can depend upon trade-union leaders to hold the strikers in check from adopting measures of retaliation. Few of them are hurt during their depredations. Once in a while, however, they drive their victims to desperation and get themselves into trouble.

For example, a few days after a fight in Farrell, Pa., that cost the strikers two dead and a dozen seriously wounded, the local secretary there, S. Coates, was on his way to Ohio to hold a meeting, when the delivery truck upon which he was riding overturned, rendering him unconscious. He woke up in a Sharon hospital. The six beds adjoining his were occupied by Cossacks, injured in the riot started by themselves in Farrell. The public knew nothing of their injuries, it being the regular thing to suppress such facts, in order to surround the dreaded Cossacks with a reputation for invulnerability. The way the latter “get even” for their casualties is to victimize and outrage as many workers as they think necessary to balance the score. But such methods cannot go on indefinitely. It will be marvellous, indeed, if some day the State Constabulary, with their policy of deliberate intimidation, are not the means of causing riots such as this country has not yet experienced in labor disputes. Not always will the unions be able to hold their men as steady in the face of brutal provocation as they did in the recent steel strike.

Hand in glove with the Cossacks in their work of terrorizing Pennsylvania’s steel towns went the less skilful but equally vicious company police, gunmen, deputy sheriffs, etc., many of whom, ex-service men, disgraced their uniforms by wearing them on strike duty. Nor were the city police, save for a few honorable exceptions here and there, appreciably better. As for the police magistrates, almost to a man they seconded unquestioningly the work of the sluggers. In fact, all the forces of “law and order” in Western Pennsylvania, official and unofficial, worked together like so many machines—in the interest of their powerful master, the Steel Trust.

Many of the armed guards were murderous criminals; penitentiary birds scraped together from the slums of the great cities to uphold Garyism by crushing real Americanism. They took advantage of the strike situation and the authority vested in them to indulge in an orgy of robbery and thievery. Dressed in United States army uniforms and wearing deputies’ badges, they even robbed strikers in broad daylight on the main streets. And if the latter dared to protest they were lucky not to be beaten up, jailed and fined for disorderly conduct. The strike committees have records of many such cases. And worse yet, more than one striker was robbed while he was in jail. Liberty bonds and cash disappeared frequently. To lose watches, knives, etc., was a common occurrence.

Picketing was out of the question, although, like many other liberties denied the steel strikers, it is theoretically permitted under the laws and court rulings of Pennsylvania. Strikers foolhardy enough to attempt it were usually slugged and arrested. Even the right to strike was virtually overthrown. The practice was for several company and city police, without warrants, to seek a man in his home, crowd in and demand his return to work. Upon refusal he would be arrested and fined from $25 to $100 for disorderly conduct. Then he would be offered his money back, if he would agree to be a scab. This happened not once, but scores, if not hundreds of times. Like practices were engaged in almost everywhere. In Monessen State Police and other “peace officers” would regularly round up batches of strikers before the mill gates. Those that agreed to go to work were set free; the rest were jailed. Many were kept overnight in an old, unlighted building and threatened from time to time with hanging in the morning, if they would not become scabs. This was particularly terrifying, as the strikers, mainly foreigners knowing little of their supposed legal rights, had very good reason to think that State Police, as well as armed thugs, would go to any extreme against them. In Pittsburgh itself, the decisive question asked petty prisoners in the police courts was, “Are you working?” Those who could show that they were strike-breakers were released forthwith; while those who admitted being on strike were usually found guilty without further questioning. Throughout the whole district, to be a scab was to be a peaceable, law abiding citizen; to be a striker was criminal.

The courts put every obstacle in the way of the strikers getting justice. In those towns where it was possible to get lawyers at all no courtesies were extended the representatives of the men. They were denied the right of cross-examination; could not get the necessary papers for appeals, and in some cases were actually ordered out of court. Attorney Roe was arrested in McKeesport for attempting to confer with a dozen of his clients in a private hall. The strikers were held under excessive bail and fined shamefully for trivial charges, to disprove which they were often denied the right to produce witnesses. The following quotations from a report by J. G. Brown, formerly president of the International Union of Timber Workers, who was a general organizer in the Pittsburgh district and later director of the legal department of the National Committee, will give an indication of the situation and some of the reasons therefor:

... The next day came the strike. The jails swarmed with arrested strikers. This was especially true in the Soho district of Pittsburgh, where are located the main entrances of the National Tube Works, and the Jones and Laughlin Company’s plants. In the afternoon two organizers who were walking down the street in this section were taken to jail, held without bail on charges of being “suspicious persons.” Information was given to us that only the Supt. of Police had authority to fix bail. He could not be located. Indeed, that these men were arrested at all was learned only through the newspapers. They were not allowed to communicate with their friends or attorneys. Attorney Brennan eventually found the Chief of Police and went bail for the men.

Deciding to utilize the right of picketing, which the laws of the state permit, a group of men were chosen for this work, captains assigned and stationed at the entrances of the mills in Soho. No sooner had they arrived there than they were hustled right on to jail, which was already filled to overflowing. Many were convicted on disorderly conduct charges; others were warned of dire things in store for them, and all were advised to return to their work in the mills.

Many women and young girls were among the victims of police brutalities in the Soho district. Located in this section were only city policemen; the State Constabulary did not “work” much within the city limits. Much wonder was created by the undiminishing brutality of the Soho police. The Central Labor Council of Pittsburgh tried to have the City Council inaugurate an investigation of the shameful state of affairs, but nothing could be done.

Shortly after the strike was called off the Pittsburgh papers carried a story to the effect that the city policemen working in the Soho district had been “paid” $150 each by the National Tube Co. It was stated also that the same men were paid a like amount by the Jones and Laughlin Company. This explains, perhaps, why justice was so blind in this section.

On the opposite side of the Monongahela river, where the Jones and Laughlin Company has other immense works the police were equally bad, the police magistrate even worse. The Police Commissioner was boss of the situation. And now come the Pittsburgh papers with the story that this very Commissioner, Peter P. Walsh, has made application to be retired from the Pittsburgh police force on half pay in order that he might accept the appointment as chief of the mill police of the Jones and Laughlin Company. The half pay allowance gives, according to reports, $1800 per year. The new position Mr. Walsh is to fill is popularly understood to carry with it a salary of $5000 per year.... The Central Labor Council is making an effort to have this matter investigated, but without serious hope of success.

When a labor committee demanded that Mayor Babcock of Pittsburgh investigate the situation, the honorable gentleman refused. He admitted that the action of the steel companies was ill-advised; the money should have been given to the pension fund, instead of to a few men; however, the matter was now past history, and there was nothing to be added to the fair name of Pittsburgh by airing it in public. The Mayor admitted, though, that he would object to having labor unions raise funds to pay policemen to favor them during strikes. So reason public officials in the steel districts.

Suppression of the rights of free speech and free assembly; gigantic organized campaigns of outlawry by the State Police and armies of selected plug-uglies; subornation and intimidation of city, county, state and federal officials and police; prostitution of the courts—these are some of the means used to crush the strike of the steel workers, and to force these over-worked, under-paid toilers still deeper into the mire of slavery. And the whole monstrous crime was hypocritically committed in the name of a militant, 100 per cent. Americanism.