William Z. Foster

The Great Steel Strike and Its Lessons

A SEA OF TROUBLES—THE POLICY OF ENCIRCLEMENT—TAKING THE OUTPOSTS—ORGANIZING METHODS—FINANCIAL SYSTEMS—THE QUESTION OF MORALE—JOHNSTOWN

Pittsburgh is the heart of America’s steel industry. Its pre-eminence derives from its splendid location for steel making. It is situated at the point where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers join their murky waters to form the Ohio, this providing excellent water transportation. Immense deposits of coal surround it; the Great Lakes, the gateway to Minnesota’s iron ore, are in easy reach; highly developed railway facilities make the best markets convenient. In the city itself there are only a few of the larger steel mills; but at short distances along the banks of its three rivers, are many big steel producing centers, including Homestead, Braddock, Rankin, McKeesport, McKees Rocks, Duquesne, Clairton, Woodlawn, Donora, Midland, Vandergrift, Brackenridge, New Kensington, etc. Within a radius of seventy-five miles lie Johnstown, Youngstown, Butler, Farrell, Sharon, New Castle, Wheeling, Mingo, Steubenville, Bellaire, Wierton and various other important steel towns. The district contains from seventy to eighty per cent. of the country’s steel industry. The whole territory is an amazing and bewildering network of gigantic steel mills, blast furnaces and fabricating shops.

It was into this industrial labyrinth, the den of the Steel Trust, that the National Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers moved its office on October 1, 1918, preparatory to beginning its work. Success in the Chicago district had made it imperative to overcome the original tactical blunder by extending the campaign, just as quickly as possible, to a national scope.

The outlook was most unpromising. Even under the best of circumstances the task of getting the enormous army of steel workers to thinking and acting together in terms of trade unionism would be tremendous. But the disastrous mistake of not starting the campaign soon enough and with the proper vigor multiplied the difficulties. Unfavorable winter weather was approaching. This was complicated by the influenza epidemic, which for several weeks suspended all public gatherings. Then came the end of the war. The workers had also just been given the basic eight hour day. All these things tended to still them somewhat and to weaken their interest in organization. What was left of this interest was almost entirely wiped out when the mills, dependent as they were on war work, began to slacken production. The workers became obsessed with a fear of hard times, a timidity which was intensified by the steel companies’ discharging every one suspected of union affiliations or sympathies. And to cap the climax, the resources of the National Committee were still pitifully inadequate to the great task confronting it.

But worst of all, the steel companies were now on the qui vive. The original plan had been conceived to take them by surprise, on the supposition that their supreme contempt for Labor and their conceit in their own power would blind them to the real force and extent of the movement until it was too late to take effective counteraction. And it would surely have worked out this way, had the program been followed. But now the advantage of surprise, vital in all wars, industrial or military, was lost to the unions. Wide awake and alarmed, the Steel Trust was prepared to fight to the last ditch.

Things looked desperate. But there was no other course than to go ahead regardless of obstacles. The word failure was eliminated from the vocabulary of the National Committee. Preparations were made to begin operations in the towns close to Pittsburgh. But the Steel Trust was vigilant. It no longer placed any reliance upon its usual methods—its welfare, old age pension, employees’ stockholding, wholesale discharge, or “extra cup of rice” policies—to hold its men in line, when a good fighting chance to win their rights presented itself to them. It had gained a wholesome respect for the movement and was taking no chances. It would cut off all communication between the organizers and the men. Consequently, its lackey-like mayors and burgesses in the threatened towns immediately held a meeting and decided that there would be no assemblages of steel workers in the Monongahela valley. In some places these officials, who for the most part are steel company employees, had the pliable local councils hurriedly adopt ordinances making it unlawful to hold public meetings without securing sanction; in other places they adopted the equally effective method of simply notifying the landlords that if they dared rent their halls to the American Federation of Labor they would have their “Sunday Club” privileges stopped. In both cases the effect was the same—no meetings could be held. In the immediate Pittsburgh district there had been little enough free speech and free assembly for the trade unions before. Now it was abolished altogether.

At this time the world war was still on; our soldiers were fighting in Europe to “make the world safe for democracy”; President Wilson was idealistically declaiming about “the new freedom”; while right here in our own country the trade unions, with 500,000 men in the service, were not even allowed to hold public meetings. It was a worse condition than kaiserism itself had ever set up. This is said advisedly, for the German workers were at least permitted to meet when and where they pleased. The worst they had to contend with was a policeman on their platform, who would jot down “seditious” remarks and require the offenders to report next day to the police. I remember with what scorn I watched this system in Germany years ago, and how proud I felt to be an American. I was so sure that freedom of speech and assembly were fundamental institutions with us and that we would never tolerate such imposition. But now I have changed my mind. In Pennsylvania, not to speak of other states, the workers enjoy few or no more rights than prevailed under the czars. They cannot hold meetings at all. So far are they below the status of pre-war Germans in this respect that the comparative freedom of the latter seems almost like an unattainable ideal. And this deprival of rights is done in the name of law and patriotism.

In the face of such suppression of constitutional rights and in the face of all the other staggering difficulties it was clearly impossible for our scanty forces to capture Pittsburgh for unionism by a frontal attack. Therefore a system of flank attacks was decided upon. This resolved itself into a plan literally to surround the immediate Pittsburgh district with organized posts before attacking it. The outlying steel districts that dot the counties and states around Pittsburgh like minor forts about a great stronghold, were first to be won. Then the unions, with the added strength, were to make a big drive on the citadel.

It was a far-fetched program when compared with the original; but circumstances compelled it. An important consideration in its execution was that it must not seem that the unions were abandoning Pittsburgh. That was the center of the battle line; the unions had attacked there, and now they must at least pretend to hold their ground until they were able to begin the real attack. The morale of the organizing force and the steel workers demanded this. So, all winter long mass meetings were held in the Pittsburgh Labor Temple and hundreds of thousands of leaflets were distributed in the neighboring mills to prepare the ground for unionization in the spring. Besides, a lot of noise was made over the suppression of free speech and free assemblage. Protest meetings were held, committees appointed, investigations set afoot, politicians visited, and much other more or less useless, although spectacular, running around engaged in. These activities did not cost much, and they camouflaged well the union program.

But the actual fight was elsewhere. During the next several months the National Committee, with gradually increasing resources, set up substantial organizations in steel towns all over the country except close in to Pittsburgh, including Youngstown, East Youngstown, Warren, Niles, Canton, Struthers, Hubbard, Massillon, Alliance, New Philadelphia, Sharon, Farrell, New Castle, Butler, Ellwood City, New Kensington, Leechburg, Apollo, Vandergrift, Brackenridge, Johnstown, Coatesville, Wheeling, Benwood, Bellaire, Steubenville, Mingo, Cleveland, Buffalo, Lackawanna, Pueblo, Birmingham, etc. Operations in the Chicago district were intensified and extended to take in Milwaukee, Kenosha, Waukegan, De Kalb, Peoria, Pullman, Hammond, East Chicago, etc., while in Bethlehem the National Committee amplified the work started a year before by the Machinists and Electrical Workers.

Much of the success in these localities was due to the thoroughly systematic way in which the organizing work was carried on. This merits a brief description. There were two classes of organizers in the campaign, the floating and the stationary. Outside of a few traveling foreign speakers, the floating organizers were those sent in by the various international unions. They usually went about from point to point attending to their respective sections of the newly formed local unions, and giving such assistance to the general campaign as their other duties permitted. The stationary organizers consisted of A. F. of L. men, representatives of the United Mine Workers, and men hired directly by the National Committee. They acted as local organizing secretaries, and were the backbone of the working force. The floating organizers were controlled mostly by their international unions; the stationary organizers worked wholly under the direction of the National Committee.

Everywhere the organizing system used was the same. The local secretary was in full charge. He had an office, which served as general headquarters. He circulated the National Committee’s weekly bulletin, consisting of a short, trenchant trade-union argument in four languages. He built up the mass meetings, and controlled all applications for membership. At these mass meetings and in the offices all trades were signed up indiscriminately upon a uniform blank. But there was no “one big union” formed. The signed applications were merely stacked away until there was a considerable number. Then the representatives of all the trades were assembled and the applications distributed among them. Later these men set up their respective unions. Finally, the new unions were drawn up locally into informal central bodies, known as Iron and Steel Workers’ councils. These were invaluable as they knit the movement together and strengthened the weaker unions. They also inculcated the indispensable conception of solidarity along industrial lines and prevented irresponsible strike action by over-zealous single trades.

A highly important feature was the financial system. The handling of the funds is always a danger point in all working class movements. More than one strike and organizing campaign has been wrecked by loose money methods. The National Committee spared no pains to avoid this menace. The problem was an immense one, for there were from 100 to 125 organizers (which was what the crew finally amounted to) signing up steel workers by the thousands all over the country; but it was solved by the strict application of a few business principles. In the first place the local secretaries were definitely recognized as the men in charge and placed under heavy bonds. All the application blanks used by them were numbered serially. They alone were authorized to sign receipts(1) for initiation fees received. Should other organizers wish to enroll members, as often happened at the monster mass meetings, they were given and charged with so many receipts duly signed by the secretaries. Later on they were required to return these receipts or three dollars apiece for them. The effect of all this was to make one man, and him bonded, responsible in each locality for all paper outstanding against the National Committee. This was absolutely essential. No system was possible without this foundation.

The next step was definitely to fasten responsibility in the transfer of initiation fees from the local secretaries to the representatives of the various trade unions. To do so was most important. It was accomplished by requiring the local secretaries to exact from these men detailed receipts, specifying not only the amounts paid and the number of applications turned over, but also the serial number of each application. Bulk transfer of applications was prohibited, there being no way to identify the paper so handled.

The general effect of these regulations was to enable the National Committee almost instantly to trace any one of the thousands of applications continually passing through the hands of its agents. For instance, a steel worker who had joined at an office or a mass meeting, hearing later of the formation of his local union, would go to its meeting, present his receipt and ask for his union card. The secretary of the union would look up the applications which had been turned over to him. If he could not find one to correspond with the man’s receipt he would take the matter up with the National Committee’s local secretary. The latter could not deny his own signature on the receipt; he would have to tell what became of the application and the fee. On looking up the matter he would find that he had turned them over to a certain representative. Nor could the latter deny his signature on the detailed receipt. He would have to make good.

To facilitate the work, district offices were established in Chicago and Youngstown. Organizers and secretaries held district meetings weekly. Local secretaries at points contiguous to these centers reported to their respective district secretaries. All others dealt directly with the general office of the National Committee.

It will be recalled that the co-operating unions, at the August 1-2 conference, agreed that the sum of one dollar should be deducted from each initiation fee for organization purposes. The collection of this money devolved upon the National Committee and presented considerable difficulty. It was solved by a system. The local secretaries, in turning over to the trades the applications signed up in their offices or at the mass meetings, held out one dollar apiece on them. For the applications secured at the meetings of the local unions they collected the dollars due with the assistance of blank forms sent to the unions. Each week the local secretaries sent reports to the general office of the National Committee, specifying in detail the number of members enrolled and turned over to the various trades, and enclosing checks to cover the amounts on hand after local expenses were met. These reports were duly certified by the representatives of the organizations involved, who signed their names on them at the points where the reports referred to the number of members turned over to their respective bodies. The whole system worked well.

Practical labor officials who have handled mass movements understand the great difficulties attendant upon the organization of large bodies of workingmen. In the steel campaign these were more serious than ever before. The tremendous number of men involved; their unfamiliarity with the English language and total lack of union experience; the wide scope of the operations; the complications created by a score of international unions, each with its own corps of organizers, directly mainly from far-distant headquarters; the chronic lack of resources; and the need for quick action in the face of incessant attacks from the Steel Trust—all together produced technical difficulties without precedent. But the foregoing systems went far to solve them. And into these systems the organizers and secretaries entered whole-heartedly. They realized that modern labor organizations cannot depend wholly upon idealism. They bore in mind that they were dealing with human beings and had to adopt sound principles of responsibility, standardization and general efficiency.

But another factor in the success of the campaign possibly even more important than the systems employed was the splendid morale of the organizers. A better, more loyal body of men was never gathered together upon this continent. They knew no such word as defeat. They pressed on with an irresistible assurance of victory born of their faith in the practicability of the theory upon which the campaign was worked out.

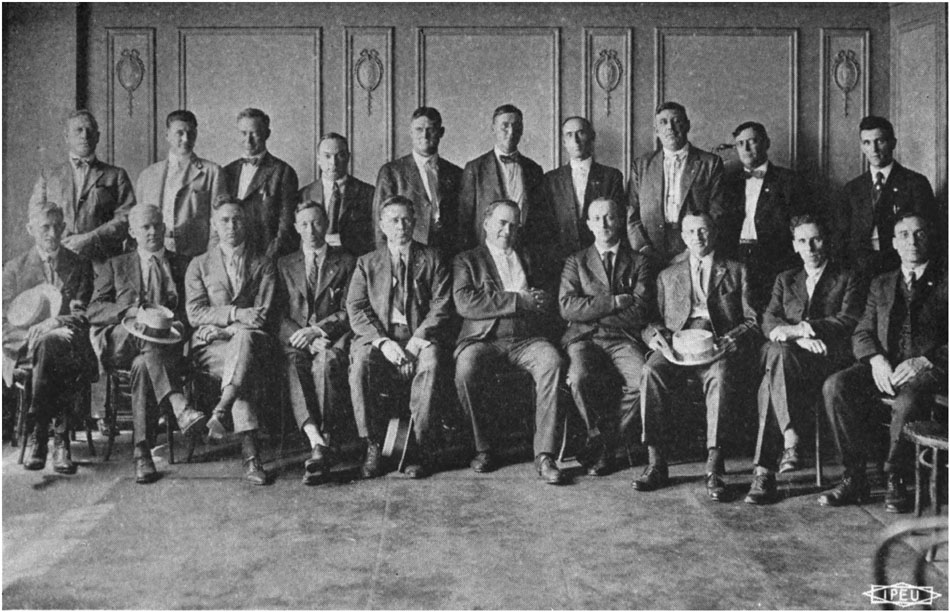

NATIONAL COMMITTEE DELEGATES

Youngstown, Ohio Meeting, Aug. 20, 1919.—Standing, left to right: F. P. Hanaway, Miners; D. Hickey, Miners; C. Claherty, Blacksmiths; R. J. Barr, Machinists; H. F. Liley, Railway Carmen; R. L. Hall, Machinists; R. T. McCoy, Molders; R. W. Beattie, Firemen; J. W. Morton, Firemen; P. A. Trant, Amalgamated Association. Seated, left to right: E. Crough, J. D. Cannon, Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers; F. J. Hardison, Blacksmiths; J. Manley, Iron Workers; Wm. Hannon, Machinists; John Fitzpatrick, Chairman; Wm. Z. Foster, Sec.-Treasurer; C. N. Glover, Blacksmiths; T. C. Cashen, Switchmen; D. J. Davis, Amalgamated Association.

The organization of workingmen into trade unions is a comparatively simple matter when it is properly handled. It depends almost entirely upon the honesty, intelligence, power and persistence of the organizing forces. If these factors are strongly present, employers can do little to stop the movement of their employees. This is because the hard industrial conditions powerfully predispose the workers to take up any movement offering reasonable prospects of bettering their miserable lot. All that union organizers have to do is to place before these psychologically ripe workers, with sufficient clarity and persistence, the splendid achievements of the trade-union movement, and be prepared with a comprehensive organization plan to take care of the members when they come. If this presentation of trade unionism is made in even half-decent fashion the workers can hardly fail to respond. It is largely a mechanical proposition. In view of its great wealth and latent power, it may be truthfully said that there isn’t an industry in the country which the trade-union movement cannot organize any time it sees fit. The problem in any case is merely to develop the proper organizing crews and systems, and the freedom-hungry workers, skilled or unskilled, men or women, black or white, will react almost as naturally and inevitably as water runs down hill.

This does not mean that there should be rosy-hued hopes held out to the workers and promises made to them of what the unions will get from the employers once they are established. On the contrary, one of the first principles of an efficient organizer is never, under any circumstances, to make promises to his men. From experience he has learned the extreme difficulty of making good such promises and also the destructive kick-back felt in case they are not fulfilled. The most he can do is to tell his men what has been done in other cases by organized workingmen and assure them that if they will stand together the union will do its utmost to help them. Beyond this he will not venture. And this position will enable him to develop the legitimate hope, idealism and enthusiasm which translates itself into substantial trade-union structure. The wild stories of extravagant promises made to the steel workers during their organization are pure tommyrot, as every experienced union man knows.

The practical effect of this theory is to throw on the union men the burden of responsibility for the unorganized condition of the industries. This is as it should be. In consequence, they tend to blame themselves rather than the unorganized men. Instead of indulging in the customary futile lamentations about the scab-like nature of the non-union man, “unorganizable industries,” the irresistible power of the employers, and similar illusions to which unionists are too prone, they seek the solution of the problem in improvements of their own primitive organization methods.

This conception worked admirably in the steel campaign. It filled the organizers with unlimited confidence in their own power. They felt that they were the decisive factor in the situation. If they could but present their case strongly enough, and clearly enough to the steel workers, the latter would have to respond, and the steel barons would be unable to prevent it. A check or a failure was but the signal for an overhauling of the tactics used, and a resumption of the attack with renewed vigor. At times it was almost laughable. With hardly an exception, when the organizers went into a steel town to begin work, they would be met by the local union men and solemnly assured that it was utterly impossible to organize the steel mills in their town. “But,” the organizers would say, “we succeeded in organizing Gary and South Chicago and many other tough places.” “Yes, we know that,” would be the reply, “but conditions are altogether different here. These mills are absolutely impossible. We have worked on them for years and cannot make the slightest impression. They are full of scabs from all over the country. You will only waste your time by monkeying with them.” This happened not in one place alone, but practically everywhere—illustrating the villainous reputation the steel companies had built up as union smashers.

Side-stepping these pessimistic croakers, the organizers would go on to their task with undiminished self-confidence and energy. The result was success everywhere. The National Committee can boast the proud record of never having set up its organizing machinery in a steel town without ultimately putting substantial unions among the employees. It made little difference what the obstacles were; the chronic lack of funds; suppression of free speech and free assembly; raises in wages; multiplicity of races; mass picketing by bosses; wholesale discharge of union men; company unions; discouraging traditions of lost local strikes; or what not—in every case, whether the employers were indifferent or bitterly hostile, the result was the same, a healthy and rapid growth of the unions. The National Committee proved beyond peradventure of a doubt that the steel industry could be organized in spite of all the Steel Trust could do to prevent it.

Each town produced its own particular crop of problems. A chapter apiece would hardly suffice to describe the discouraging obstacles overcome in organizing the many districts. But that would far outrun the limits of this volume. A few details about the work in Johnstown will suffice to indicate the tactics of the employers and the nature of the campaign generally.

Johnstown is situated on the main line of the Pennsylvania railroad, seventy-five miles east of Pittsburgh. It is the home of the Cambria Steel Company, which employs normally from 15,000 to 17,000 men in its enormous mills and mines. It is one of the most important steel centers in America.

For sixty-six years the Cambria Company had reared its black stacks in the Conemaugh valley and ruled as autocratically as any mediæval baron. It practically owned the district and the dwellers therein. It paid its workers less than almost any other steel company in Pennsylvania and was noted as one of the country’s worst union-hating concerns. According to old residents, the only record of unionism in its plants, prior to the National Committee campaign, was a strike in 1874 of the Sons of Vulcan, and a small movement a number of years later, in 1885, when a few men joined the Knights of Labor and were summarily discharged. The Amalgamated Association, even in its most militant days, was unable to get a grip in Johnstown. That town, for years, bore the evil reputation of being one where union organizers were met at the depot and given the alternative of leaving town or going to the lockup.

Into this industrial jail of a city the National Committee went in the early winter of 1918-19, at the invitation of local steel workers who had heard of the campaign. A. F. of L. organizer Thomas J. Conboy was placed in charge of the work. Immediately a strong organization spirit manifested itself—the wrongs of two-thirds of a century would out. It was interesting to watch the counter-moves of the company. They were typical. At first the officials contented themselves by stationing numbers of bosses and company detectives in front of the office and meeting halls to jot down the names of the men attending. But when this availed nothing, they took the next step by calling the live union spirits to the office and threatening them with dismissal. This likewise failed to stem the tide of unionism, and then the company officials applied their most dreaded weapon, the power of discharge. This was a dangerous course; the reason they did not adopt it before was for fear of its producing exactly the revolt they were aiming to prevent. But, all else unavailing, they went to this extreme.

Never was a policy of industrial frightfulness more diabolically conceived or more rigorously executed than that of the Cambria Steel Company. The men sacrificed were the Company’s oldest and best employees. Men who had worked faithfully for ten, twenty or thirty years were discharged at a moment’s notice. The plan was to pick out the men economically most helpless; men who were old and crippled, or who had large families dependent upon them, or homes half paid for, and make examples of them to frighten the rest. The case of Wm. H. Seibert was typical; this man, a highly skilled mechanic, had worked for the Cambria Company thirty years. He was deaf and dumb, and could neither read nor write. He was practically cut off from all communication with his fellow workers. Yet the company, with fiendish humor, discharged him for being a union agitator. For every worker, discharge by the Cambria Company meant leaving Johnstown, if he would again work at his trade; for most of them it brought the severest hardships, but for such as Seibert it spelled ruin. With their handicaps of age and infirmities, they could never hope to work in steel mills again.

For months the Company continued these tactics.(2) Hundreds of union men were thus victimized. The object was to strike terror to the hearts of all and make them bow again to the mastery of the Cambria Steel Company. But the terrorists overshot the mark. Human nature could not endure it. They goaded their workers to desperation and forced them to fight back, however unfavorable the circumstances. The National Committee met in Johnstown and ordered a ballot among the men. They voted overwhelmingly to strike. A committee went to see Mr. Slick, the head of the Company, who refused to meet it, stating that if the men had any grievances they could take them up through the company union.

This company union played a large part in the drama of Johnstown. It was organized late in 1918 to forestall the trade unions. Such company unions are invariably mere auxiliaries to the companies’ labor-crushing systems. They serve to delude the workers into believing they have some semblance of industrial democracy, and thus deter them from seeking the real thing. They consist merely of committees, made up for the most part of hand-picked bosses and “company suckers.” There is no real organization of the workers. The men have no meetings off the property of the companies; they lack the advice of skilled trade unionists; they have no funds or means to strike effectively; they are out of touch with the workers in other sections of the industry. Consequently they have neither opportunity to formulate their grievances, nor power to enforce their adjustment. And little good would it do them if they had, for the lickspittle committees are always careful to see that they handle no business unless it relates to “welfare” work or other comparatively insignificant matters.

Company unions are invariably contemptible. All of them are cursed with company dictation, and all of them lack the vivifying principles of democratic control; but it is doubtful if a more degraded specimen can be found anywhere than that of the Cambria Steel Company. Without a murmur of protest it watched the company abolish the basic eight hour day late in 1918. Nor did it raise a finger to help the multitude of unfairly discharged union men. It habitually pigeonholed all real grievances submitted to it. But what else could be expected of a committee from which the company boldly discharged every man who dared say a word for the workers?

By referring the men’s grievances to the despised company union, Mr. Slick only added fuel to the fire. A strike loomed threateningly, but just as it was about to break, Mr. Slick lost his job, presumably because of his unsuccessful labor policy. He was supplanted by A. A. Corey, Jr., formerly general superintendent of the Homestead Steel Works. Thinking perhaps the change in personnel might involve a change in policy, the committee approached Mr. Corey. He, too, refused to meet with it, stating publicly that the management would not deal with the representatives of outside organizations, but would take up the men’s grievances, either through the company union, or “through any other accredited committee selected by the men in any way that is agreeable to them from among their own number.” The last proposition was acceptable, and with joy the men held big open mass meetings of union and non-union men, and elected their committee. But their joy was short-lived. Mr. Corey, unashamed, wrote the committee that he had acted hastily before, and said, “I have had no previous experience with arrangements in the nature of collective bargaining, but a careful survey of this plan (company union), which I have since had time to make, convinces me that it makes full and complete provision for every contingency which can arise between the company and its employees.” And then to make the men like this bitter medicine, the Company discharged an active member of the committee. All these events consumed many weeks and wore away the late winter and early spring months.

Mr. Corey’s double-dealing provoked a fresh strike crisis; but by heroic measures the organizers repressed it. At all times a strike in Johnstown alone against the united steel companies was considered a move of desperation, a last resort to be undertaken only because nothing else could be done. But now relief was in sight. Spring was at hand and the national movement fast coming to a head. Its committees were knocking at the doors of the steel companies. The exposed and invaluable Johnstown position had to be held until this main army could come up and relieve it. So the Johnstown workers were told that they must refrain from counter-attacking, that they had to take all the blows heaped upon them and hold their ground at all costs.

And right nobly they did it. In spite of the bitterest hardships they built up and developed their organizations. In this they were unwittingly but powerfully aided by the company union. Several weeks before the big strike the officials took the hated general committee to Atlantic City, wined them and dined them and flattered them, as usual, and then had them adopt a set of resolutions condemning the national movement of the steel workers and endorsing long hours, low wages and heavier production as the remedy for prevailing bad conditions. This betrayal was the last straw. It provoked intense resentment among the men. Whole battalions of them, the most skilled and difficult in the plant to organize, walked down and joined the unions in protest. Almost 3000 enrolled the week after the resolutions were adopted. But it was always thus. Every move that the Cambria made the unions turned to their advantage. They outgeneraled the Company at every turn.

It was almost pitiful to watch the later antics of the haughty and hitherto unchallenged Cambria Company, humbled in its own town by its own workers. A few weeks before Labor day the unions, innocently presuming the mills would be closed as usual on that day, decided to have a parade. Then the strategical experts of the Company became active. A warning was issued that every man marching in the parade would be summarily discharged. The unions would not brook this unwarranted and cold-blooded attack. They promptly sent word to the Company that if a single man was discharged the whole plant would be stopped the next day. It was a clear-cut issue, and Johnstown held its breath. When Labor day came the city saw the biggest demonstration in its history. Fifteen thousand organized workers defied their would-be masters and marched. The Company swiftly backed water. And the next day not a man was discharged. It was a victory well worth the heroic efforts and suffering of the previous eight months.

When the great strike broke on September 22 the Johnstown workers went into the fight almost one hundred per cent. organized, and with about the same percentage of grievances. So few men were left in the plant that the Company had to ask the unions to give them help to shut down their furnaces, and to keep the fire protection in operation. All the power of the great corporation, which had made $30,000,000 the year before, could not forestall the unions. It had no arrow in its quiver that could strike fear to the hearts of its workers; no trick in its brain pan that could be substituted for industrial democracy.

And Johnstown was only one point in the long battle line. Its experiences were but typical. Each steel town had its own bitter story of obstacles encountered and overcome. Youngstown, Chicago, Bethlehem, Cleveland, Wheeling, Pueblo, Buffalo and many other districts, each put up a hard fight. But one by one, despite all barriers, steel towns all over the country were captured for unionism.

1. As a side light on organizing methods, it may be noted that the temporary receipts were red, white and blue cards. The patriotic foreigners were proud to carry these emblematic cards pending the time they got their regular cards. More than one man joined merely on that account.

2. In its war against unionism the Cambria Steel Company held nothing sacred, not even the church. During the campaign the Reverend George Dono Brooks, pastor of the First Baptist Church of Johnstown, took an active part, speaking at many meetings and generally lending encouragement to the workers. For this crime the company punished him by disrupting his congregation and eventually driving him from the city, penniless.