MIA > Archive > Cliff > Incomes policy

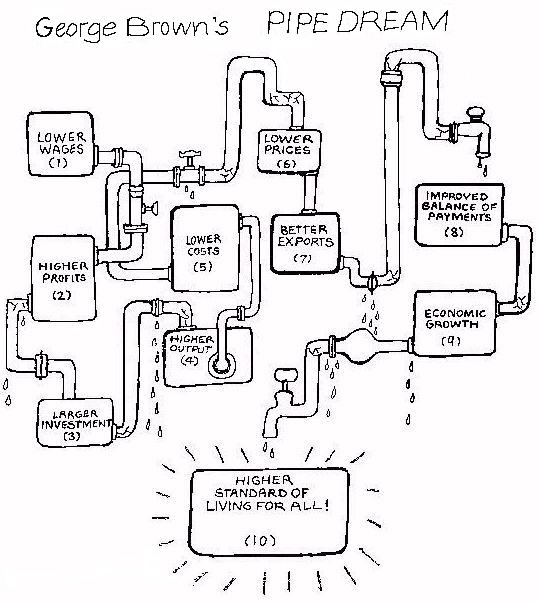

In the first chapter we suggested some of the reasons for the growing respectability of the idea of planning among the capitalists. Planning has become a very popular activity in the Western capitalist countries, and of course a central place in this planning is given to incomes policy. Here we shall try to make clear the logic behind the ideas of the planners, by giving a picture of what it is that George Brown and his co-thinkers imagine will happen if they can only introduce an incomes policy into Britain. This can be represented by a diagram. The basic assumption is that there is an intimate causal connection between each of the items in the diagram, and that one item inevitably leads into the other in a neat and beautiful chain. The diagram looks like this:

|

It’s a beautiful picture, with each item running into the next one and all adding up to a better standard of living for everyone in Britain. The only thing wrong with it is that it is entirely useless. It’s completely remote from the facts of life in capitalist Britain, and about as helpful in understanding reality as a chocolate machine would be in solving problems in higher mathematics. We will follow the argument stage by stage and point our some of the flaws.

The first link, between lower wages and higher profits, is true, on one condition: goods must not be sold at an undercutting price. In other words, surplus value must not only be produced but also realised. If, because there is a very high degree of competition, the capitalist can’t sell at a profit, then this link won’t hold.

As for the second link, it is one of the hoariest of legends that higher profits guarantee higher investments. In the actual conditions of British capitalism the relationship between profits and investment is very far from being as direct or as rational as that. Many British industries spend only a tiny proportion of their profits on investment. For instance, in 1955 the clothing and leather industries had net profits of £48 million, but they spent only £3 million on capital formation. The food, drink and tobacco industries spent only 10 percent of their net profits on investment. In metal manufacture, bricks, pottery and glass the figure was only 12 to 13 percent, and in shipbuilding, engineering and electrical goods it was only 15 percent. [1]

The Department of Scientific and Industrial Research revealed that the entire shipbuilding industry in 1958, with exports valued at £60 million, spent on research and development only “about £282,000”: “The DSIR report on machine tools was hushed up even more, but one estimate is that the total spent on research in the whole industry, with an output valued at £150 million, is less than £1 million a year”. [2]

Indeed, the whole shipbuilding industry employed not more than 120 qualified men on research and development. [3] And investment in the shipyards between 1951 and 1954 didn’t even cover the wear and tear in the industry – investment was about £4 million a year, while equipment written off as worn out, etc amounted to £9 million a year. [4]

The assumption lying behind this link between profits and investment overlooks not only the monopolistic organisation of industry and its effect on investment, but also the effect of government policies. In the recurrent balance of payments crises since the war – in 1947, 1949, 1951, 1955, 1957, etc., etc. – one of the first things to be hit each time has been industrial investment. This, after all, is one of the causes of Britain’s stagnation.

The third link in the chain, the assumption that higher investment must lead to corresponding increases in productivity and output, is even weaker. Some seven years ago Andrew Shonfield assumed that an investment in new manufacturing capacity worth £100 will probably produce at least £33 of additional output each year. [5] He even tried to support his argument by adducing figures to show that the rate could be still higher, quoting T. Barna who calculated that the figure would be £45. [6]

However, the assumption that the national income will grow at a fixed rate associated with a certain rise in capital investment completely overlooks the question of the rate of use of capital investment. To have a lot of expensive machinery is one thing, but to use it at full capacity is quite another. The following table shows that the rate of use of capital investment varies quite considerably between Western capitalist countries:

|

ANNUAL AVERAGE RATE OF GROWTH (1950-60) [7] |

|||

|

|

(1) Growth of GNP |

(2) Growth of capital |

(1) as a proportion |

|

West Germany |

5.0 |

4.6 |

1.09 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

France |

3.9 |

3.0 |

1.30 |

|

Netherlands |

3.6 |

3.5 |

1.03 |

|

United Kingdom |

2.1 |

2.9 |

0.72 |

Thus in France every unit of investment gave an increase in the national cake almost double that in Britain.

Between 1957 and 1961 investment in Britain went ahead very quickly, while there was no acceleration in the growth of the national income. The ratio of the increase in capital to the resultant increase in output was one of 7.5 to one. [8]

The reason why a rise in investment does not lead inevitably to a corresponding increase in the size of the national product is to be found in the “leakage” (or flaw) of unused capacity. If every machine installed in the factories were used to its capacity, then probably Shonfield’s or even Barna’s optimistic estimate would fit the facts. As it is, their estimates are just wrong. In the Institute of Economic and Social Research inquiry in 1963 into the mechanical engineering industry, only 6 percent of the firms reported that they had no spare plant capacity. On average the firms in the industry indicated that with the plant and equipment they already had they could increase output by some 22 percent. Firms in the motor vehicle industry could increase output by 15 percent. [9]

The best proof, perhaps, that there is no necessary connection between increased investment and corresponding increases in output lies in the fact that while the investment ratio in Britain rose rapidly and reasonably steadily in the post-war years (from 12.8 percent of the gross national product in 1950 to about 17.2 percent in 1963) industrial output did not show a parallel rise.

The first link, between larger output and cheaper costs, is true. The second link, from cheaper costs to lower prices, would be true if we completely overlooked the existence of monopolies. Monopolies in fact play a major part in keeping prices high. It is important that this is understood in the labour movement, since high prices in Britain are often explained as due to rising wages. It is taken as self-evident by many that “cost-push” resulting from trade union wage demands is at the root of the wage-price spiral that Britain has suffered over the last two decades, and is thus the cause of Britain’s declining share in world trade. Thus the general council of the TUC, in the report recommending George Brown’s incomes policy to the Conference of Trade Union Executive Committees, argued that “the main reason why British exports lagged behind those of other countries was that incomes generally have grown disproportionately faster”. [10]

The facts, however, do not confirm this contention. Compared with its European rivals, Britain is certainly not suffering from greater wage inflation. Earnings in manufacturing industry have gone up half as much again in France and Germany, and twice as much in Italy. And as far as earnings per unit of output – in other words, wage costs – are concerned, the picture is the same, as this table shows.

|

THE FIVE-YEAR MYSTERY |

||||

|

|

Percentage increase (1959-64) in: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hourly |

Earnings per |

Output per |

Exports |

|

|

Britain |

35 |

13 |

20 |

28 |

|

West Germany |

54 |

19 |

30 |

66 |

|

France |

50 |

19 |

26 |

57 |

|

Italy |

74 |

24 |

41 |

128 |

|

United States |

15 |

4 |

20 |

53 |

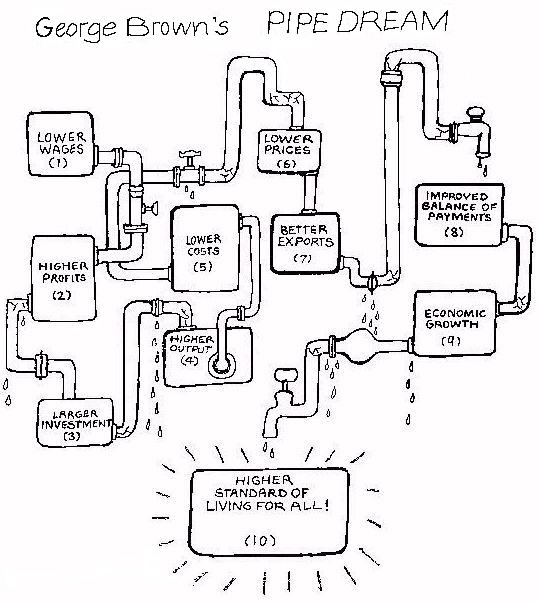

In fact as the following chart, adapted from DATA Journal (June 1965), demonstrates clearly, British wages are at a generally lower level than among the main European competitors:

|

Comparative wages: estimated hourly earnings of industrial workers, |

|---|

|

|

Source: Barclays Bank reprot on the Common Market |

It is difficult, in view of these figures, to hold that British prices are high because of high wage costs. Thus it is extremely difficult to see much strength in the link between cheaper costs and lower prices.

The first link is partly true – but only partly. Selling abroad (like selling anywhere) is not only dependent on price, but also on other factors, like the quality of the goods being offered, the delivery dates that can be guaranteed, after-sales service, and so on. These are all matters of great importance to potential foreign buyers, and they are not necessarily connected with prices at all. As for the second link, between increased exports and an improved balance of payments, so much claptrap is talked about this that we need to go into this question in a little more detail. Britain has lived almost permanently in a balance of payments crisis (or the threat of one) ever since the Second World War. The years 1953, 1959 and 1963 were the only odd-numbered years in which there was no such crisis. But let’s get the picture clear. Were these crises the result of Britain’s failure to export enough?

The first thing that has to be said is that, while Britain’s imports today are about five times bigger than before the Second World War, exports are eight times bigger. Exports have grown faster than imports.

In the first five years after the war there was a balance of payments deficit only in 1946-47, and a surplus thereafter. During the 1950s, a decade of supposedly chronic inflation, the deficit on the visible trade balance went down radically – from £302 million in 1938 and an average of nearly £250 million for 1952-54 to little more than £50 million for 1955-59. [12] If we take rising prices into account, the deficit on the balance of trade went down between 1938 and 1955-59 by as much as 90 percent. On present day prices, the pre-war adverse trade balance (£302 million in 1938) would today have amounted to some £1,000 million. Yet instead it has been only £50 million. If one excludes spending by the government abroad (mainly on military establishments, with which we will deal later), the years 1960-64 saw an average surplus in the current account of £260 million a year. [13]

“In the 13 years from 1950 to 1962 there were deficits on current account [and that includes expenses by the government abroad] in only four years, and there was an average surplus of £70 million”. [14]

In fact the numerous crises in the balance of payments were caused, not by deficits in the current balance of payments – which has become increasingly healthy – but by movements of capital out of Britain. As Thorneycroft said at the time of the 1957 crisis, when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer, “Our problems therefore arise not so much as a trader but as a banker and overseas investor. Our difficulties are much more on capital than on current account”. [15] And Callaghan recently made the same point.

One authority summed the situation up very clearly when he said:

The United Kingdom have exported capital on a scale never before equalled ... official estimates for long term capital exports since the war yield an accumulated total of some £4,500 million. In monetary terms this was as much as the whole of the United Kingdom’s overseas investments before the war (which of course had been accumulated over 100 years). [16]

In the five years 1960-64 the annual average export of private capital reached some £318 million.

The trend towards increasing exports of capital is inherent in the nature of modern capitalism. In the face of increasing international competition large companies are finding it more and more useful to establish subsidiary companies abroad. This is one expression of the growing conflict between the productive forces and the boundaries of the national state in contemporary capitalism. Thus in 1955 it was estimated that the sales made by subsidiary companies of US firms operating outside the United States were worth more than twice the annual volume of US exports. [17] The top 200 corporations in the US are said to derive a quarter of their incomes from foreign investments. [18] Similarly, large British companies like Unilever and ICI are finding it increasingly profitable to build subsidiaries all over the world.

While the export of capital worsens Britain’s balance of payments position, its impact is made that much greater by the fact that nowadays the profits from the investments abroad are not brought back to Britain in the way they used to be. In the past the profits earned abroad were remitted regularly to the country from which the investment was made. But today, both at home and abroad, there is a tendency towards the reinvestment rather than the redistribution of profits. We have already said that the large shareholder nowadays tends to prefer profits in the form of capital gain to profits in the form of dividends, and the same is true of large companies with investments abroad. Today the majority of companies prefer to reinvest the profits from their successful foreign investments in overseas businesses – in line with the general tendency of “ploughing back” – rather than to bring the money home.

It is altogether utopian to try to stop the export of capital under capitalism – in other words, as long as industry and finance are owned and controlled by a tiny minority. This is especially true of British capitalism, whose home market consists of only some 50 million people. The only thing a capitalist government can do to slow down the flow of capital abroad is to make the conditions for home investment more attractive to the capitalists:

The only way to prevent the runaway of capital is by making Britain as attractive a place to the owners of capital as any possible alternative abroad. This at once sets pretty narrow limits to what the government can do about taxation, about social expenditure, about nationalisation, and a number of other major political issues. Here in fact is the vicarious reassertion of the political power of the owners of wealth. [19]

As long as industry is privately owned and as long as the commercial banks are privately owned there are many loopholes in any attempt that may be made to control the movement of capital. Those who have large sums of money which they wish to move abroad can do it quite easily, whatever the government of the time thinks is good for Britain.

Let’s consider a simple example of how this can be done. If a car producer sells a car, say in Argentina, and the price of the car is £1,000, all he has to do is to write £950 on his invoice and arrange that, while the £950 is transferred to Britain, the other £50 will be salted away for him in a bank in Argentina. Or if an importer of meat buys £1,000 worth of Argentinian beef, all he has to do is to arrange for an inflated invoice of £1,050 to be sent to him – he sends off the money, and again the extra £50 is put away for him in Argentina. When we remember that Britain’s foreign trade is worth some £10,000 million a year, it’s easy to see that a “mistake” of only 1 percent in pricing will mean a loss of £100 million to Britain. And a “mistake” of a couple of percentage points can very easily go undetected. Ferranti made a mistake in its tendering for the Bloodhound Mark 1 missile and got 72 percent profit instead of the 7 percent that had been planned, and that mistake took many months to detect!

Or again, there is another way out to capital, through what might be called the “Bahamas Gap”:

The Bahamanian tax structure is, to say the least, unusual. Government income comes from stiff import duties, and a $2 levy collected from each departing tourist. There is no income tax, capital gains tax, inheritance tax, or tax on real estate. Resident millionaires can invest their money in profitable ventures, such as property, without worrying about taxes. British firms can channel funds through Nassau offshoots, and use profits for overseas operations, without Mr Callaghan getting a look-in. [20]

The ease with which capital can be transferred out of the country explains how wealthy English people managed to stay on the French Riviera and spend thousands of pounds in the period when exchange control didn’t allow you to take more than £25 out of the country. Probably every one of those tourists took his allotted £25 with him, but added, say, 25,000 shares in ICI or Shell. “A man holding high and responsible office” in exchange control told Andrew Shonfield, “Nobody but small fry takes any notice of exchange control”. [21]

The attitude of many City financiers was expressed in memorable terms by Mr W.J. Keswick (director of a merchant bank as well as of the Bank of England) in a letter he wrote to the Far East firm of Jardine Matheson of Hong Kong. Mr Keswick advised the firm to sell a substantial portion of its holdings of British government securities and to switch its funds to North American securities. He wrote, “This is anti-British and derogatory to sterling but on balance, if one is free to do so, it makes sense to me”. [22]

Of course, as the government knows, even if exchange control did work perfectly, the prohibition or limitation of capital exports could only have a very detrimental effect on the working of the British capitalist economy. For if the Labour government were to impose an embargo on capital exports – making the idiotic assumption for the moment that this could be done without the nationalisation of industry and of the commercial banks – the capitalists’ immediate reaction would be to go “on strike”. In other words, they wouldn’t invest at all, but would wait for a change of government and for the reopening of channels for the export of capital. After all, if one can get 30 percent profit on capital invested abroad, and only 15 percent on capital invested in Britain, it’s still very worthwhile to wait for a few years to invest abroad. Besides, if the government allows that 15 percent profit on investment in Britain is quite fair and all right, why should it say there’s anything wrong with 30 percent abroad?

As well as the capital exports leak, there is another leak of resources from Britain that has a very bad effect on the balance of payments. This is the expenditure in foreign currency on keeping British troops stationed abroad.

In 1934-38 the government’s overseas expenditure amounted to £6 million a year. In 1956 military expenditure abroad, including the Suez operation, rose to £178 million. [23] In 1964 the cost in foreign currency of the military bases abroad was as high as £334 million. [24] This was divided roughly as follows:

|

Overseas bases, 1964 [25] |

||

|

|

Uniformed |

Approximate annual |

|

BAOR (Germany) |

52,000 |

85 |

|---|---|---|

|

Singapore & Malaya |

32,000 |

100 |

|

Aden & Saudi Arabia |

12,500 |

20 |

|

Gan (Maldives) |

500 |

2 |

|

Bahrein |

3,000 |

10 |

|

Cyprus |

12,500 |

20 |

|

Other |

16,500 |

53 |

|

TOTAL |

128,000 |

290 |

It should be understood that the above table refers only to expenses in foreign currency. The total cost of keeping British troops abroad is a great deal larger. Thus, for instance, Denis Healey, Secretary of State for Defence, gave the cost of keeping British troops in Germany at £180 million in 1964 [26], while the cost in foreign currency amounted to only £85 million.

A few items in this expense account are worth noting: first, naval officers’ flats in Gibraltar cost over £9,000 each to build [27]; second, “an establishment of 115 dogs in Singapore (including 102 dog handlers) cost a total of £110,101 to maintain, or not far short of £1,000 per dog per annum”. [28]

The cost of keeping one police dog in Singapore “to discipline the natives” is about the same as the cost of keeping five old age pensioners in Britain. Harold Wilson is right – socialism is about priorities!

“By 1968 an infantry battalion of the Rhine army will cost six times as much to equip as it did in 1963”. [29] What is true of the Rhine is equally true of our “mission” east of Suez.

As long as Britain is dominated by big business, and as long as profits in the Middle East are a great deal fatter than they are in Britain, the keeping of troops there to defend “our oil” is inevitable. And as long as big business dominates and the NATO alliance is its by-product, “our role” east of Suez is justified.

Military expenditure damages the balance of payments in other ways too, quite apart from the direct spending of foreign currency on “our” bases abroad. Firstly, military production has directly lost Britain certain overseas business which could not be fulfilled because the productive resources of the British engineering industry were stretched to the limit by arms orders. Secondly, it has had the more indirect effect of holding back investment and so has held back expansion of our industrial capacity, which would among other things have produced more exports. Thirdly, military production has monopolised certain of our scarce resources – particularly research and electronics – and this again has affected economic growth, including growth of exports. As The National Plan explained:

As a nation we spend as much on defence as we do on industrial plant and machinery; appreciably more than we do on all durable consumer goods, from motor cars to TV sets, electric fires and furniture; and nearly 50 percent more than on publicly financed education of all kinds. The defence programme now uses some 35-40 percent of total national research and development expenditure and about one fifth of the qualified scientists and technologists engaged in it. [30]

And, fourthly, the arms that are produced – particularly aeroplanes – depend in part on expensive imports of foreign materials and so cause an increase in the import bill.

Now, if capital flows out of Britain at the rate of £300 million a year, and another £350 million flows out in the form of military expenditures in foreign currency, these two items alone have to be balanced by exports worth £650 million a year. Actually, as exports have an import content of 20 percent, this figure is much higher, nearer £800 million. Thus British workers have to produce goods worth more than £2 million a day just to pay for these two items by themselves.

If the Labour government is not ready to do anything more than a spot of tinkering with the flow of capital exports, and is not ready to put an end to the cost of keeping British troops overseas, then there is no other choice. The Labour government can only strengthen the balance of payments by sacrificing the workers’ standards to help “our” export drive.

Together with the two basic leaks, capital exports and military expenditure abroad, both of which cause radical instability in the balance of payments, there is a third factor which makes any sterling crisis worse once it starts. This is Britain’s involvement in the international banking business, and it has aggravated the pressures to which the pound has become exposed.

Even before the crisis of November 1964 the British reserves amounted to only one tenth – actually slightly less than one tenth – of the value of Britain’s foreign trade. And since the pound is an international reserve currency, it had also to cope with fluctuations in the trade of other members of the sterling area. By contrast the reserves of Germany, which does not have an international reserve currency, are about a quarter of the annual foreign trade, and those of the United States amount to about one half of foreign trade. Britain’s role as an international banker has contributed enormously to its proneness to currency crises.

The movements of “hot money” only add to the general instability, and the cost to the economy is incalculable:

It is probably not going too far to say that the Bank’s advocacy of bank rate excesses has cost the UK something like $2,000 million in additional interest payments on overseas debt during the past ten years or so – an amount closely approaching the sum we have to borrow from the IMF to survive the latest crisis. [31]

The indirect cost was much greater, though it is quite immeasurable. To defend sterling as an international currency, again and again a succession of Chancellors of the Exchequer have had to put their feet on the brakes – and the national economy has paid the price in stagnation.

More and more business circles have come to the not very surprising conclusion that British capitalism could very well do without the advantages of sterling as an international reserve currency:

Our experiences during the past year may well be seen as endorsing the view that the UK would be better off if it were to withdraw from its international banker activities altogether and leave the job of meeting the world’s need for a medium of exchange and all related tasks to others. And it is not without significance in this connection that, though a number of continental countries have been in a good position for many years to push out into this field, they have been careful to avoid doing so, taking the view that it was a game not worth the candle. [32]

However, getting out of the game isn’t quite so easy. Firstly, as the same writer in the Financial Times put it, “The business is so closely tied up with our sterling debts that such a retreat would be easier said than done”. [33]

Secondly, there are the vested interests of the City of London. After all, the City’s earnings from its banking, insurance, merchanting and brokerage services reached an estimated £185 million in 1963. [34]

Thirdly, many of the industrial groups, like the great food processing and tobacco combines, with 15 percent of their input coming from imports and only 4 percent of their output being exported, side with the City as regards sterling. [35] In sum, to get sterling away from its international standing, when it has served British capitalism so well in the past, is extremely difficult. To do it would demand an upheaval of at least some strong citadels of power and privilege.

The factors leading to the great instability in the British balance of payments – capital exports, spending on armed forces overseas, and the position of sterling as an international currency – make for the heavy dependence of British economic policy on the international banking community. In Harold Wilson’s language, there are “the gnomes of Zurich” – only it should be remembered that some of the most powerful members of that eminent fraternity are also among the giants of the City of London. As Shonfield put it:

We should recognise frankly that, having become so dependent on the mood and whim of foreign investors for the country’s essential solvency, Britain has already lost control over a large part of her domestic policy. The brutal fact is that there are many things which the government might like to do, but dare not do at the moment because of the fear of the effect which they might have on sentiment abroad. [36]

The truth of this was driven home more recently. Thus, for instance, the Financial Times stated on 6 October 1965:

As for the proposed early warning legislation itself, it is as well to be clear about the origins of this. It was, quite simply, the condition laid down by the international monetary authorities, and in particular by the United States Secretary of State for the Treasury, Mr Fowler, for the September support operation for sterling. Hence Mr Brown’s unexpected and desperate dash to Brighton to see the TUC.

In conclusion, between the three items – lower prices, increased exports and improved balance of payments – there is a connection. They are not entirely unlinked. But unfortunately there are so many flaws that even quite a large wage restraint at the beginning of the process would have almost no impact at all on the balance of payments situation.

Even if George Brown’s incomes policy worked, and if after years of wage restraint the national cake did increase in size, who can guarantee that workers’ standards would radically improve? It is only under exceptional conditions that the share of wages in the national income rises under capitalism (it did, briefly, in the period of the last war, though it soon fell back again), but it is always possible for the share of wages to fall. Indeed, there is an inherent tendency under capitalism for wages to do so. This tendency can only be prevented by vigorous trade union activity on the part of the working class. In the long run higher wages will always be passed on in the form of higher prices, to protect the rate of profit, but there is no “countervailing tendency” in capitalism which pushes wages up together with higher profits or higher prices:

A gain in their (the workers’) real standard of living of nearly 44 percent in 11 years – 3½ percent per annum compound – does not stand up against a rise of 200 percent (in real terms) in the value of equity shares which the owners of equity shares enjoyed, which was at the rate of 10½ percent per annum compound. And the workers never managed to win a larger share of the national income. Their share remained at a little over 42 percent throughout the Conservative regime. [37]

And this was a period, moreover, in which there was no “incomes policy” to inhibit the workers’ demands! Nor are things better under Labour in this respect:

Britain was one of only four countries where workers’ actual purchasing power decreased last year, according to a report by the International Labour Organisation published in Geneva yesterday. The others were Ireland, Hungary and South Korea. In industrialised countries generally, workers were more prosperous last year than ever before, says the report. [38]

And with international competition increasing each year, the distance between the sacrifice that the workers are asked to make now and the payment they are told they will get later is likely to grow even longer.

For socialists, of course, there is also a more fundamental question to be considered. An incomes policy that succeeds means a working class that is submissive, and that demands no more than its rulers offer. Such a working class, without spirit or fight, might crawl and quarrel for the crumbs beneath its masters’ tables, but would hardly be likely to demand the whole loaf. However well fed, would such a working class be well placed to achieve its own emancipation? After all, there are many farmers who warm their cowsheds to get more milk, but we are still waiting to hear of the farmer who gives over control of his shed to the cows.

1. M. Barratt Brown and J. Hughes, Britain’s Crisis and the Common Market (London, 1961), p.4.

2. M. Barratt Brown and J. Hughes, Britain’s Crisis, p.4.

3. A. Shonfield, Observer, 24 April 1960.

4. A. Shonfield, British, p.42.

5. A. Shonfield, British, p.38.

6. A. Shonfield, British, p.46.

7. S.R. Sargent, Out of Stagnation, p.3.

8. T. Balogh, Planning for Progress (1963), p.19.

9. NIESR, Economic Review, February 1964, p.6.

10. TUC, Productivity, Prices and Incomes (1965), p.7.

11. Table drawn from Nigel Lawson, St George and the Incomes Policy, Financial Times, 10 March 1965.

12. A.R. Conan, The Unsolved Balance of Payments Problem, Westminster Bank Review, November 1963.

13. UK Balance of Payments 1965 (London, 1965).

14. C. McMahon, Sterling in the Sixties (London, 1964), p.9.

15. Times, 25 September 1957.

16. A.R. Conan, The Impact of Post-War Capital Movements, Westminster Bank Review, August 1963.

17. V. Perlo, The Empire of High Finance (New York, 1957), p.294.

18. V. Perlo, The Empire, p.295.

19. A. Shonfield, British, p.222.

20. W. Davis, They Sell Sun And Tax Escapism In The Bahamas, Guardian, 24 January 1966.

21. A. Shonfield, British, p.211.

22. Letter of 16 September 1957, printed in Minutes of Evidence Taken Before the Bank Rate Tribunal (December 1957), p.101.

23. A. Shonfield, British, p.105.

24. Economic Trends, March 1965.

25. M. Chichester, Imperial Relics or Outpost of the Free World, Statist, 4 December 1964.

26. Times, 29 October 1965.

27. Military Expenditure Overseas, Ninth Report of the Estimates Committee for 1963-64, para.44.

28. Military Expenditure Overseas, para.32.

29. Economist, 17 July 1965.

30. The National Plan (London, 1965), p.182.

31. Lombard, Financial Times, 18 October 1965.

32. Lombard, Financial Times, 12 August 1965.

33. Lombard, Financial Times, 12 August 1965.

34. Times, 30 July 1965.

35. M. Barratt Brown, After Empire, pp.313-314.

36. Observer, 2 April 1961.

37. N. Davenport, The Split Society, Spectator, 22 November 1963.

38. Guardian, 20 January 1966.

Last updated on Last updated 3.5.2003