ASSETS OF THE SIX BIG BANKS IN EGYPT

AND THE CONNECTIONS AMONG THEM THROUGH DIRECTORS

T. Cliff, Some Features of Capitalist Economy in the Colonies, Fourth International, Vol.8 No.4, April 1947, pp.114-117.

Transcribed by Ted Crawford.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

In his book, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin analyses the economy of the most developed countries. It will be of interest to investigate to what degree those elements, which Lenin defined as characteristic of capitalism in its highest stage, exist in the industrial and banking system of the colonies. It will also be interesting to see what the dissimilarities are, and how the different elements – those the colonies have in common with the highly developed countries, and those in which they are different – are combined. This analysis will perhaps help us to throw some light on a very important aspect of the law of uneven and combined development.

As an example, we shall take Egyptian economy, which is typical.

Lenin gives the following characteristics of the economy of the developed capitalist countries in the period of imperialism:

Let us see to what extent these features exist in Egyptian economy.

Owing to the paucity of statistics it is impossible to calculate the degree of concentration of industry according to the value of its product, number of workers or motor power. The only calculation that can be made, and then not very accurately, is that of the concentration of capital in industry. Although not exact, it throws a clear light on the degree of concentration of Egyptian industry.

There are no figures of the total quantity of capital in the enterprises of different sizes, except for the 250 largest, but there are data of the number of enterprises sorted according to the quantity of capital invested in them. We have made use of these figures, taking the maximum figures for the capital of the small enterprises (thus, for instance, if 3089 enterprises have £50-99 per enterprise, we have assumed that altogether they have 3089 X £100). This method of calculation does not over-estimate the concentration of capital in industry, but on the contrary, underestimates it:

|

|

No. of |

Per cent of |

Amount of Capital |

Per cent of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Enterprises with capital |

89,194 |

96.9 |

5,300,000 |

3.9 |

|

Enterprises with capital |

2,014 |

2.2 |

2,600,000 |

2.0 |

|

The 250 largest enterprises |

250 |

0.27 |

125,800,000 |

92.0 |

Thus beside 91,208 petty enterprises there are 250 with an average capital of half a million pounds each. These figures show that in Egypt the concentration of capital is relatively much higher than in the most highly developed capitalist countries for which Lenin gives figures.

Going hand in hand with the concentration of capital, the centralization of ownership is also very great. This can to some extent be measured by taking the data of the centralization of directorships. The following figures include only those people who have five or more directorships (1943):

|

|

Number of people |

Total number of directorships |

|---|---|---|

|

5 to 9 directorships |

43 |

278 |

|

10 to 14 directorships |

14 |

158 |

|

15 and more directorships |

9 |

185 |

|

Total |

66 |

621 |

But we must take into account that there are many families a number of whose members are directors. As there was no other way of making the following calculation, a list was made of all the directors’ families based on the surname and address, and a table made of the concentration of directorships according to this list. Actually, according to names and addresses of directors alone, it is very difficult to decide the family ties, as there are many members of one family who have different names and addresses. It must therefore be understood that in actuality the concentration of directors is much greater than the table shows (1943):

|

|

No. of families |

Total no. of directorships |

|---|---|---|

|

5-9 directorships |

50 |

325 |

|

10-14 directorships |

13 |

146 |

|

15 and more directorships |

15 |

342 |

|

Total |

78 |

813 |

Thus, of a total number of directorships of 1,620 in 441 companies, 621 are concentrated in the hands of 66 people, and at least 813 (actually many more) in the hands of 78 families.

It is evident that this high degree of centralization and concentration of capital is a strong basis for the organization of industry into big monopolies.

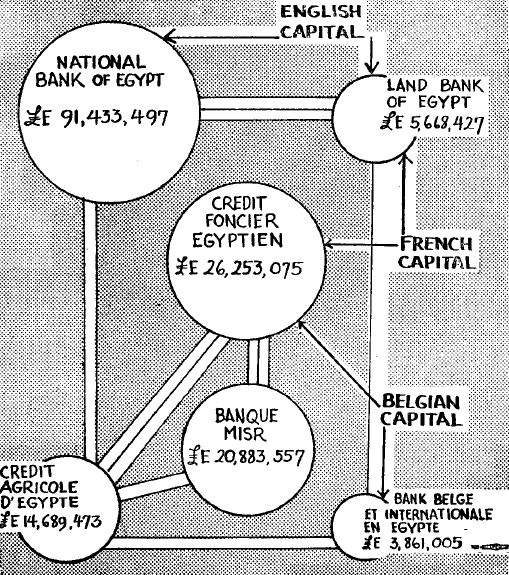

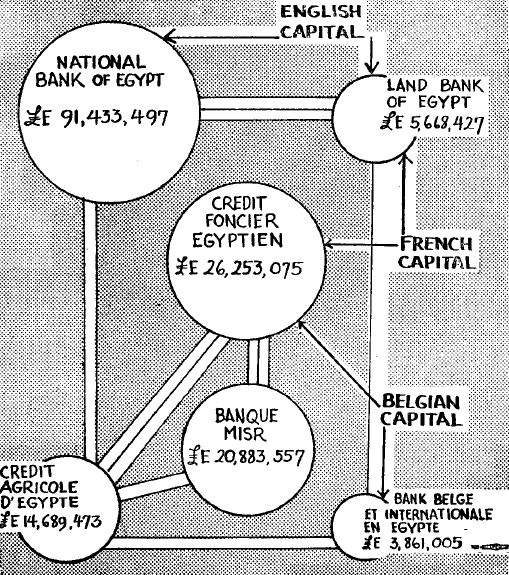

There are only six important banks active in Egypt. These banks in 1942 together had assets amounting to £E162,200,000, while the assets of all the other banks did not go above £E10,-000,000. Thus the concentration of the banking system in Egypt is much higher than the figures Lenin gives, for the concentration of banking capital in the highly developed countries.

Many arteries connect these banks with one another: the participation of one bank in the capital of another, the purchase or interchange of shares, the giving of credit by one to the other, etc. Unfortunately, statistical material is much too scarce for us to be able to show the degree of intertwining of the six banks. We shall be compelled to suffice with illustrating the connections between them through the directorships. In the following illustration every circle signifies the assets of the banks, and every line connecting them signifies a director sitting on the boards of both banks.

|

ASSETS OF THE SIX BIG BANKS IN EGYPT |

|---|

|

To what degree this banking system has control over the financial operations of the economy as a whole, to what degree banking capital merges with industrial capital, will become clear from data showing the number of directorships concentrated in the hands of the directors of the above banks. The above banks control through their directors (1943):

|

98.6 per cent |

of the Egyptian banking assets.* |

|

|

88.6 per cent |

of assets of the |

light, water and power companies. |

|

92.4 per cent |

of assets of the |

transport companies.** |

|

100 per cent |

of assets of the |

insurance companies |

|

52.0 per cent |

of assets of the |

industrial enterprises.*** |

|

81.8 per cent |

of assets of the |

hotel companies |

|

71.6 per cent |

of assets of the |

land companies.**** |

|

63.0 per cent |

of assets of the |

commercial companies |

|

* This is besides the Ottoman Bank, Barclays Bank, and a few other banks, e.g. Banco di Roma, whose centers are not in Egypt but which are active in the country. |

||

The industrial capitalist of the Eighteenth and first half of the Nineteenth centuries was liberal. He did not want the intervention of the state in economic life except in the interests of the protection of private capitalist property from “anarchy.” By liberty he meant his defense from the arbitrariness of the state bureaucracy and the nobility. The capitalist magnate of the Twentieth Century has no cause to fear the state bureaucracy. His strength is sufficient for him to negotiate with the ministers as the representative of a power on an equal footing with the state. And not only this; he even desires the state’s increasing intervention in foreign affairs – by a policy of imperialist expansion, wars, etc. – and also in domestic affairs – having a “strong hand” against the proletariat. If during the period of industrial capital, therefore, no close connection existed between the bureaucracy of the capitalist state and the individual capitalist, now, in the period of imperialism, finance capital grows into the state. In face of the close connection between the different enterprises in Egypt and the high degree of merging of industrial with banking capital, it is readily understood that the relation of the big capitalists to the state is not like the relation of the bourgeoisie toward the state in the Europe of the Eighteenth and first half of the Nineteenth centuries, but rather like that of the bourgeoisie in the developed capitalist states of the Twentieth Century. The dependence of the state on an imperialist power increases even more the tendency of the growing of finance capital into the state.

This tendency is revealed in many forms – the dependence of the state finances on the subscription of its securities by the big banks, the dependence of industry on government orders and subventions and on the customs policy, etc. It takes on its most open form in the personal ties between the directorships of the different companies and the bureaucracy of the state.

Thus among the 696 directors of all the companies holding 1,620 directorships, there were (1943):

|

|

Number of people |

Number of directorships |

|---|---|---|

|

Former Prime Ministers |

3 |

34 |

|

Former Ministers |

25 |

95 |

|

Senators |

20 |

111 |

|

Members of the Chamber of Deputies |

9 |

28 |

|

High officials |

14 |

36 |

|

Total |

71 |

304 |

There are two features of colonial economy which differentiate it from the highly developed countries:

We shall not dwell on the first point which is self-evident, but shall deal with the second.

The banks have strong, direct connections with agriculture. According to one calculation, of all the paid-up capital of the different companies whose main investments are in Egypt, about 43.4 per cent belongs to mortgage companies, and 6.6 per cent to agricultural and urban land companies. These investments are made either directly in big plantations (as, for instance, in Kom Ombo Co., which employs 35,000 workers) or – and this in the main – in loans to large landowners. They are a strong bond connecting the banking system with feudal property relations. The banks will lose all their investments if feudal property relations are overthrown. The imposition of this tremendous banking system on the feudal agrarian economy is thus a great brake on the development of the productive forces in agriculture. The millions upon millions of pounds that stream every year out of agriculture, retard the accumulation of capital in agriculture, and thus conserve the outworn mode of production, while worsening the position of the masses of producers (agricultural workers and tenants). Because of the connections between the different banks, and between them and industry, the direct connections between the banks and the feudal estates strongly link together modern industry and the feudal property relations. This connection is strengthened by the fact that many big industrialists are at the same time large feudal landowners.

There are other indirect, but not less important, links between feudal property relations and Egyptian industry.

The young industry of Egypt could not compete with the industries of the metropolitan countries, could not accumulate sufficient quantities of capital, except by the purchase of cheap labor power and raw materials, which means the harsh exploitation of the workers and peasants. This is made possible for them by the existence of feudalism which keeps the standard of life of the masses of agricultural toilers – the reserve army of industry – very low. Only the low wages can explain the fact that while the productivity of labor in Egyptian industry is lower than in the developed countries (in US industry the industrial gross output per worker was £1,434 in 1937, in Egypt it was only £309 in 1941) the organic composition of capital (the relation between the capital invested in machines, buildings and raw materials, and that invested in labor power), the rate of exploitation and the rate of profit, are much higher even than in US industry.

Comparing the organic composition of capital in Egyptian industry in 1942 (calculated from a census undertaken by the Egyptian Federation of Industry, which encompassed about half the industrial undertakings of its members) with that of USA in 1929 (from L. Corey, The Decline of American Capitalism, pp.114-123), we find:

|

|

Total |

Annual |

Annual |

Wages as |

Wages as |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

USA |

$52,694 million |

$47,110 million |

$11,621 million |

22.1 |

24.7 |

|

Egypt |

£E125,820,000 |

£E39,000,000 |

£E5,213,000 |

4.2 |

13.4 |

Thus the portion of wages in the total industrial capital is five times smaller in Egypt than USA. But in order not to commit an error, it must be remembered first that the figures for the USA include all the manufacturing enterprises, while those for Egypt include only the large ones, and secondly it is not at all certain that the figures relating to the investment of capital in Egyptian industry are not very much exaggerated. In any case, even if we take these two considerations into account, we see that the organic composition of big Egyptian industry reaches or even surpasses that in the USA.

Generally a higher composition of capital goes hand in hand with a high productivity of labor. How then, can the facts be reconciled that in Egypt the composition of capital is not lower than in the USA, but at the same time the gross product per worker is 4.6 times smaller than that in the USA? This is explained first by the low educational level, and consequent low skill, of the workers, and secondly, and this is the most important reason, by the low wages. (The wage of the Egyptian industrial worker is about a ninth of that of his American fellow.) If the wage of the Egyptian worker had been equal to that of the American, it would then have constituted 37.8 per cent of the total capital, as against 22.1 per cent in the USA. Low wages are thus the lever by which Egyptian industry reaches and over-reaches the high organic composition of capital in US industry.

Low wages, together with modern technique, explain the very high rate of exploitation. According to one calculation the average net income of industry in 1922 was £E120 per man occupied in industry. And seeing that the wages of the workers and officials only came to £E30-40 on an average for the year, we may assume that every worker produced an average surplus value of £E80-90, which gives a rate of exploitation of 200-300 per cent. If we leave out of account the primitive handicrafts and consider the technical advance which took place in industry in the last twenty years, and which was not accompanied by any noticeable rise in the wage rate, we shall easily arrive at the conclusion that the rate of surplus value in Egypt reaches 300-400 per cent, while in the USA, for instance, it was 155 per cent in 1929 (Corey, ibid., p. 83).

From the above we can pass over to a calculation of the rate of profit in Egyptian industry. As there are no statistical data for the rate of profit in industry as a whole, our calculation will perforce have to be based on the conclusions we have drawn above. Seeing that in the industries encompassed by the above-mentioned census, wages make up 4.2 percent of all capital, and that the rate of exploitation amounts to 300-400 per cent, the rate of profit is 12-17 per cent. As against this rate of profit of 12-17 per cent, the rate of profit in American industry in 1929 – the peak year of the prosperity – was 7.5 per cent (Corey, ibid., p.123).

We should come to a similar conclusion if we adopted another method of calculation. In the article “Company Profits in Egypt 1929-1939” (L’Egypte Contemporaine, 1941) a calculation is given of the net profit in 21 important industrial companies. The net profit in 1929-41 was £E13,141,000, while the capital was £E7,721,000. This means that the average rate of profit was 13.8 per cent.

Of course during the war the rate of profit increased to a great extent, and it is clear that it is at least double that in the highly developed capitalist countries.

The fact that banking and industry draw their sustenance from the feudal agrarian relations, while at the same time pre-serving them, does not keep them from coming into conflict with these relations; for the purchasing power of the masses is limited by them, and thus also the possibilities of industrial development. [1] We must not be astonished, therefore, to find that while the productivity of labor in Egyptian industry, as we have already said, is much lower than in the US, and the percentage of the population employed in industry is very low (6.4 per cent), the local market was nearly saturated by local industrial products even before the war. According to a reliable calculation the consumption of industrial products in Egypt was nearly £E90 millions per annum. The production of local industry was £E65-70 millions. Thus, already then, local industry satisfied nearly three-quarters of the industrial consumption of the country. Since that time Egyptian industry has made big strides forward.

While the buying of industrial products by the masses of people is limited by the low purchasing power that their small incomes afford them, the buying of industrial products by the wealthy is limited first because of the fact that a part of them are foreign capitalists living in and buying the products of other countries, and secondly because of the fundamental law of capitalist accumulation – the tendency of the capitalist to in-crease his savings as against his consumption.

Egyptian industry’s necessity of extending its markets can therefore not be fulfilled except by raising the purchasing power of the masses in city and country, which means the emancipation of the fellaheen from their feudal burdens, and the abolition of the monopolistic position of foreign capital in the national economy. In the conditions of Egypt, to raise the wages of the industrial workers, however, means to cut into profits, which goes against the grain of the “national” bourgeoisie; the same reason dictates their opposition to the overthrow of feudalism and imperialism.

That feudalism and imperialism, together with the monopolistic organization of industry and banking with which they are linked, become a greater and greater impediment on the development of the productive forces is shown by the fact that to-day, when such a small percentage of the population is occupied in industry, the phenomenon of a surplus of capital is already evident. This receives expression in the big loans which the colonies gave to Britain during World War II. The capitalists of Egypt, both local and foreign, loaned a sum of £400 million to Britain, nearly double the total British investment in Egypt. These £400 millions are basically different from the more than £200 million that the British invested in Egypt.

While the British investment built railways, irrigation schemes, industries, etc., the Egyptian loan to Britain served in the main to finance war expenditures in Egypt. The former came mainly as a result of the fact that the rate of profit in Egypt is higher than in Britain; the latter gives a very low rate of interest – for we must not forget that Britain is the ruler and Egypt the ruled. But despite the differences between the export of capital from Britain, and its “export” from Egypt, we must keep in mind their common characteristics: In the same way as the surplus of capital in the most developed countries shows that capitalism is becoming a greater and greater impediment on the development of their productive powers, so the fact that Egypt and other colonies gave such tremendous loans, shows the same as regards the economies of these countries. After what we have said above, it should be clear that if these £400 million were tomorrow converted into industrial equipment and imported into Egypt, the scope of industry in Egypt would be more than trebled. The absorption of such a vast sum would demand either a revolution in the mode of production in agriculture or the raising of the standard of life of the masses in the town. Such changes, however, cannot be realized under the existing regime. (In all probability, therefore, the next world crisis will see a decline in the number of workers, not only in the metropolitan countries, but also in the colonies.)

Thus the surplus of capital, which is characteristic of decaying, agonizing capitalism, becomes one of the important features of capitalism in the colonies.

With the establishment of the tremendous monopolies, the socialization of production reaches a very high stage. At the same time, achieving its peak of development, is the banking system, which, according to Marx, “presents indeed the form of universal bookkeeping and distribution of the means of production on a social scale, but only the form.” The content of the activity of the monopolies and banks is not social, but individual – subordinated to the interests of a tiny minority. And there is a sharp contradiction between the form and the content. The existence of highly social production signifies the maturity of the material basis for socialism; individual appropriation signifies the oppressive, reactionary character of capitalism. As Lenin so well explained, the fact that free competition gave way to monopolies, and that banking capital is merged with industrial capital, proves that capitalism in the developed countries is ripe for the socialist revolution.

The fact that the industrial and banking system in the colonies is built on the same pattern as that of the most developed countries, proves that capitalism in the colonies, too, is ripe for the socialist revolution. Not only is world economy in its entirety ripe for socialism, but the most important colonies (e.g. Egypt, India, China) are ripe for the socialist revolution in themselves. (Nor does the fact that only a small minority of the population of the colonial countries is employed in industry. while the great majority toil in the feudal agricultural economy. refute the fact that the colonies are ripe for the socialist revolution. On the contrary, a combination of ultra-modern industry and banking with a backward, feudal agriculture, brings the class antagonisms in the society as a whole to extreme limits.)

The above does not contradict the fact that there is a struggle between the colonial bourgeoisie and imperialism over the division of the surplus value. Only it is clear from the above that there are very limited boundaries to this struggle; these being the economic connections of the “national” bourgeoisie with imperialism and feudalism, and of greater weight – its fear of the uprising of the masses.

The analysis of the fundamental features of capitalism in the colonies brings new confirmation of the theory of the permanent revolution, of the unbroken link connecting the anti-imperialist, anti-feudal and anti-capitalist struggle for national independence and social revolution.

1. This will become clear from a calculation made by W. Cleland in an article Egypt’s Population Problem which appeared in L’Egypte Contemporaine, Cairo, 1937:

|

Manufactured goods annually consumed |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

£E |

|

£E |

|

Clothing |

from 2.870 |

to |

5.040 |

|

Bedding, blankets |

from 1.000 |

to |

1.250 |

|

Other items of consumption |

from 1.060 |

to |

1.240 |

|

Total |

from 4.930 |

to |

7.530 |

|

Average |

£E6.230 |

and per capita, £E1.250 |

|

Last updated on 12.2.2009