Illusion and Reality, Christopher Caudwell 1937

Poetry grasps a piece of external reality, colours it with affective tone, and makes it distil a new emotional attitude which is not permanent but ends when the poem is over. Poetry is in its essence a transitory and experimental illusion, yet its effects on the psyche are enduring. It is able to live in the same language with science – whose essence is the expression of objective reality – because in fact an image of external reality is the distributed middle of both propositions, the other term being external reality in the case of science, the genotype in the case of poetry. This is not peculiar to poetry; it is general to all the arts. What is peculiar to poetry is its technique, and the particular kind of emotional organisation which this technique secures. None the less, an analysis of poetry should also throw light on the technique of the other arts.

The other important artistic organisation effected by words the story. How does the technique of poetry compare with that of the story?

In a poem the affects adhere directly to the associations of the words. The poet has to take care that the reader’s mind does not go out behind the words into the external reality they describe before receiving the affects. It is quite otherwise with the story. The story makes the reader project himself into the world described; he sees the scene, meets the characters, and experiences their delays, mistakes and tragedies.

This technical difference accounts also for the more leisurely character of the story. The reader identifies himself with the poet; to both the words arise already soaked with affect, already containing a portion of external reality. But the novel arises as at first only an impersonal description of reality. Novelist and the reader stand outside it. They watch what happens. They become sympathetic towards characters. The characters move amid familiar scenes which arouse their emotions. It seems as if they walked into a world and used their own judgment, whereas the world presented by the poet is already soaked in affective colour. Novel-readers do not immediately identify themselves with the novelist, as a reader of poetry does with the poet. The reader of poetry seems to be saying what the poet says, feeling his emotions. But the reader of the story does not seem to be writing it; he seems to be living through it, in the midst of it. In the story, therefore, the affective tones cling to the associations of external reality. The poem and the story both use sounds which awake images of outer reality and affective reverberations; but in poetry the affective reverberations are organised by the structure of the language, while in the novel they are organised by the structure of the outer reality portrayed.

In music the sounds do not refer to objects. They themselves are the objects of sense. To them, therefore, the affective reverberations cling directly. Although the affective reverberations of poetry are organised by the structure of the language, this structure itself is dependent on the “meaning” – i.e. on the external reality referred to. But the structure of music is self-sufficient; it does not refer to outer reality in a logical way. Hence music’s structure itself has a large formal and pseudo-mathematical component. Its pseudo-logical rigour of scale and chord replaces the logical rigour of external meaning. Thus in music poetry and the novel the sound symbol has three different functions: in the novel it stands for an object in external reality; in poetry for a word-born mental complex of affective reverberation and memory-image; in music for art of a pseudo-external reality.

The social ego or subjective world is realised in artistic phantasy by the distortion of the external world. But for a world to be distorted into an affective organisation it must have a structure which is not affective (subjective) but logical (objective). Hence the socially recognised laws of music, which are pseudo-logical laws. They correspond to the laws of language, also socially recognised, which are pseudo-objective and are distorted by poetry, but not by the novel, which distorts the time and space of objective reality.

A logical external world can only exist in space and time. Hence the musical world exists in space and time. The space movement of the scale, so that a melody describes a curve in space as well as enduring in time. Although a melody is in time, it is organised spatially. Just as a mathematical argument is static and quantitative, although it “follows on” in time, so a melody is timeless and universally valid. It is a generalisation corresponding to the classificatory content of science. It is colourless and bare of quality in its essence. It draws from the ego a universal emotional attitude within the limits of its argument.

Harmony introduces into music a temporal element. Just as space can only be described in terms of time (a succession of steps), so time can only be described in terms of space (a space of time imagined as existing simultaneously, like a panorama). Time is the emergence of qualities. Hence two qualities sounding simultaneously describe time in terms of space. Just as the evolutionary sciences import from external reality a perspective of a whole field of qualities evolving (yet here visualised by an all-seeing eye as already fully developed), so harmony brings into music a whole rich field of temporal enrichment and complexity. It individualises music and continually creates new qualities. It was therefore no accident but a result of the way in which the bourgeoisie “continually revolutionises its own basis,” that the richest development of harmony in music should have coincided with the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the evolutionary sciences and a dialectical view of life. There was a parallel temporal movement in story and symphony. It was equally no accident that this musical development should have coincided with a technical development which on the one hand facilitated the instrumental richness of bourgeois orchestras, and on the other hand by its increase of communications made men’s lives and experiences interweave and counterpoint each other like a symphony.

In the world of melody undifferentiated man faces a universal nature or static society, precisely as in poetry. In the novel and the world of harmony a man contemplates the rich and complex movement of the passions of men in a changing and developing world.

Rhythm was prior to either melody or harmony if anthropological researches are any guide, and we assumed that a rhythmic dancing and shouting was the parent also of poetry. The external world of music exists, not to portray the world but to portray the genotype. The world has therefore to be dragged into the subject; the subject must not be squeezed out into the object. Rhythm, because it shouts aloud the dumb processes of the body’s secret life and negates the indifferent goings-on of the external universe, makes the hearer sink deep down into himself in a physiological introversion. Hence the logical laws of music, in spite of their externality and materality, must first of all pay homage to rhythm, must be distorted by rhythm, must be arranged round the breath and pulse-beats and dark vegetative life of the body. Rhythm makes the bare world of sound, in all its impersonality, a human and fleshy world. Melody and harmony impress on it a more differentiated and refined humanity, but a great conductor is known most surely by his time. The beating baton of the conductor says to the most elaborate orchestra: “All this complex and architectural tempest of sound occurs inside the human body.” The conductor is the common ego visibly present in the orchestra.

When man invented rhythm, it was the expression of his dawning self-consciousness which had separated itself out from nature. Melody expressed this self as more than a body, as the self of a member of a collective tribe standing in opposition to the universal otherness of nature. Rhythm is the feeling of a man; melody the feeling of Man. Harmony is the feeling of men, of a man conscious of himself as an individual, living in a world where the interweaving lives of society reflect the orchestral pageant of growing and developing nature.

Just as the rhythm of music is physiological and distorts the object to its pattern so as to draw it into the body, so the periodicity and ordering which is the essence of mathematics is “natural” and logical, and squeezes the ego out of the body into the object, so that it follows the grain of external nature.

The collective members of the tribe do not conflict in their broad desires and do not require a mutual self-adjustment to secure freedom for each, because the possibility of large inequalities of freedom does not arise. There is no real surplus of freedom. The life of the primitive corresponds almost exactly to a blind necessity. So small is the margin that to rob him of much is to rob him of life itself. Therefore just because it is, in the sum, so scanty, it is shared equally by all, and Nature, not other men, is a man’s chief antagonist. But the individuation produced by the division of labour and a corresponding increase in productivity, raises this mutual interplay of different characters in conflict to a vital problem. Appearing first with the static and logical simplicity of tragedy, it is in bourgeois civilisation developed as the novel with a more flexible and changing technique. The development of orchestration in music has a similar significance as a road to freedom.

The decay of art due to the decline of bourgeois economy is reflected in music. Just as the novel breeds a characteristic escape from proletarian misery – “escape” literature, the religion of capitalism – so music produces the affective massage of jazz, which gratifies the instincts without proposing or solving the tragic conflicts in which freedom is won. Both think to escape necessity by turning their backs on it and so create yet another version of the bourgeois revolt against a consciousness of social relations. In contrast to the escape from proletarian misery in bourgeois literature, there rises an expression of petty bourgeois misery. This characteristic expression is the anarchic bourgeois revolt, the surréalisme that attempts to liberate itself by denying all convention, by freeing both the inner and outer worlds from social-commonness and so “releasing” art into the magical world of dream. In the same way, petty bourgeois music advances through atonality to an a anarchic expression of the pangs of a dying class. The opium of the unawakened proletariat mixes with the phantastic aspirations of the fruitlessly rebellious lower stratum of the bourgeoisie.

Because the world of music with its logical structure is pseudo-external and drawn out of the genotype, like the logical content of mathematics, the “infant prodigy” is possible in both. The full development of the novel and the evolutionary sciences requires even in genius the maturity of concrete experience. Because the external reality of music is self- generated, it is as if music directly manipulated the emotions of men.

Language expresses both external reality and internal reality – facts and feelings. It does so by symbols, by “provoking” in the psyche a memory-image which is the psychic projection of a piece of external reality, and a feeling which is the psychic projection of an instinct. But language is not haphazard group of symbols. It must be organised. This organisation is given in the arrangement of the symbols but cannot be itself symbolised by these symbols. Wittgenstein, to whom we owe this conception, saw it as a projective correspondence between the symbols and outer reality. But there is also a projective correspondence between the symbols and inner reality, and the final shape or pattern is the result of a tension or contradiction between the two organising forces. Both orderings are shared in common with the thing projected. If this is a part of external reality, we may say symbols and symbolised share the real world; if it is a projection of internal reality, they share are the same affective manifold or social ego. Considered separately, these orderings are only abstractions. They cannot in concrete language be separated. In concrete language only their tense mutual relation is reflected, and this is the subject-object relation – man’s active struggle with Nature.

In poetry the manifold distorted or organised by the affective forces of the common ego is the logical or grammatical manifold inhering in the arrangement and syntactical organisation of the words themselves. Of course this corresponds to a similar logical arrangement “out there” in the external reality symbolised. It corresponds, but it is not the same and therefore permits an affective organisation more direct, “languagy” and primitive than that of the novel, where the logical manifold organised by common ego is “out there” in the external reality symbolised. Hence poetry is more instinctive, barbaric and primitive than the novel. It belongs to the age when the Word is new and has a mystic world-creating power. It comes from a habit of mind which gives a magical quality to names, spells, formulae and lucky expressions. It belongs to the “taken for granted” knowledge in language which when we discover it consciously – as in logic’s laws – seems to us a new, inhuman and imperious reality. The poetic Word is the Logos, the word-made-flesh, the active will ideally ordering; whereas the novel’s word is the symbol, the reference, the conversationally pointing gesture.

In music the logical manifold is the formal or structural element in music, corresponding to the grammatical or syntactical element in language. It comprises the stuff-ness, the conventions, laws, scales, permitted chords, and instrumental limitations of musical theory. It is the impersonal and external element in music. This is distorted affectively in time and space by rhythm, melody and harmony. Wovon man nicht spechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen, (“whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”), ended Wittegenstein, asserting in a mystical form that since language corresponds to facts, it cannot speak of non-factual entities, but must fall back on mystical intuition. This is untrue. By arbitrarily limiting the function of language Wittgenstein excludes it from the provinces it has long occupied successfully. It is precisely art – music, poetry and the novel – which speaks in the affective manifold what man nicht sprechen kann in the logical manifold.

The even pulse of rhythmic time contrasts with the irregularity of time successions observed in the outside world. Man naturally seizes therefore on the few natural periodicities – day and night, months and years. Hence the conception of order and therefore number is given to us physiologically, and mathematical calculation consists in giving different names to different periodicity groups; at first digital symbols, later separate written characters. The ego is projected on to external reality to order it. Subjective affective periodicity is the parent of number, therefore in mathematics affective time must be distorted by orderings found in external reality. The outer manifold is the main organising force. In music external periodicity is affectively distorted to follow the instinctive ego. The affective manifold is here the organising force. The musician is an introverted mathematician. The “lightning calculator” is an extraverted conductor.

To summarise:

Mathematics uses spatial orderings of periodicities drawn from subjective sources, these periodicities being distorted to conform with external reality.

Music uses affective orderings of periodicities drawn from objective sources, these periodicities being distorted to conform with internal reality.

In poetry the affective rhythm is logico-spatial, not affective-temporal. Unlike the basic rhythm of mathematics, it is not distorted by cognitive material. It asserts the tempo of the body as against that of environment. Metre denies external time, the indifferent passing on of changing reality – by “marking time” and drawing in the object to it.

Music, language, mathematics, all mere sounds, can yet symbolise the whole Universe and express the active relation of internal to external reality. Why has sound, a simple physical wave system, become so apt a medium for the symbolisation of life in all its concreteness?

In the life of animals external reality has been explored by three distance receptors round which, as Sherrington has shown, the brain has evolved; these are physico-chemical smell, sound and sight. On the whole light-wave reception has proved its superiority for this purpose and sound therefore became specialised as a medium of inter-species communication. Among birds and tree-apes this would follow naturally from the engrossment of eye-sense by the demands of balance, aerial or arboreal. Long have cries – mere sounds – been the simple voice of the instincts among the warm-blooded animals from which we evolve. Long have our ears been tuned to respond with affective association to simple sounds. Birds, with their quick metabolism the most emotional of animals, express with sound the simple pattern of their instincts in an endlessly repeated melodic line. But man goes a step further, along the line indicated by the warning cry of birds. The demands of economic co-operation – perhaps for hunting – made essential the denomination of objects and processes in external reality not instinctively responded to. Perhaps gesture stepped in, and by a pictographic mimicking of a piece of external reality with lips and tongue, man modified an instinctive sound, a feeling-symbol, to serve also as the symbol of a piece of external reality. Language was born. Man’s simple cries, born of feeling, of primitive sympathy, of gesture, of persuasion, become plastic; the same cry now stood for a constant piece of external reality, as also for a constant judgment of it. Something was born which was music, poetry, science and mathematics in one but would with time fly apart and generate all the dynamism of language and phantasy between the poles of music and mathematics, as the economical operation which was its basis also developed.

It is no mere arbitrary ordering of emotion which music performs. It expresses something that is inexpressible in a scientific language framed to follow the external manifold of reality. It projects the manifold of the genotype. It tells us something that we can know in no other way; it tells us about ourselves. The tremendous truths we feel hovering in its cloudy reticulations are not illusions; nor are they truths about external realities. They are truths about ourselves, not as we statically are, but as we are actively striving to become.

In addition to the sound-symbolical arts, there are the visual or plastic arts – painting, sculpture and architecture. It is easier to see how these fit into our analysis. The visual sense – in all animals, eked out by tactile corrections – has been that sense used most consistently to explore external reality, while the hearing sense has been used to explore that particular part of external reality which consists of other genotypes. Sound mediates between genotype and genotype – the animal hears the enemy or the mate. Light mediates also between genotype and non-genotypical portions of external reality.

As a result, when we make a visual symbol of external reality, such as a diagram or a drawing, it is naturally made projective of external reality and not merely symbolic. Except in onomatopoeia, words individually are not mechanically projective of things like a photograph, but are only symbolic and therefore “conventional.” A drawing, however, is directly projective of reality without necessarily the mediation of pseudo-grammatical rules or conventions. This is shown by the resemblance between a drawing and a photograph.

In drawing and sculpture bits of external reality are projected into a mock world, as in a drawing of a flower or a sculpture of a horse. This picture must have in common with the external reality from which it is drawn something not describable in terms of itself – the real or logical manifold or, more simply, the “likeness.”

But line and colour also have affective associations in their own right. These must be organised in an attitude towards the mock world, the “thing” projected. This must be an affective attitude, which is what the painting or sculpture has in common with the genotype, or affective manifold, and cannot be itself symbolised by a drawing, since it is inherent in the drawing. To the naive observer this appears as a distortion in the drawing as a non-likeness to external reality. But of course it is really a likeness, a likeness to the affective world of the genotype.

For the purpose of this brief survey, the only distinction that need be made between painting and sculpture is that one is three-dimensional and the other two-dimensional. Thus painting selects two out of the three dimensions of external reality – or rather to be accurate, it selects two out of the four dimensions, for unlike music, poetry and the story, the plastic arts lack the fourth dimension, time. Pictures do not begin at one moment in time and end at another. They are static; they do not change. All arts must select from external reality in some way, otherwise they would not have any looseness at the joints to give play for ego-organisation. They must have one degree of freedom.

Line and colour, symbolising real objects, are organised by the ego-reality projected. The result is a new emotional attitude to a piece of reality. After viewing a Rembrandt or a Cézanne we see the exterior world differently. We still see the same external reality, but it is drenched with new affective tones and shines with a bright emotional colouring. It is a more “appetising” world, for it is the appetitive instincts which furnish the aesthetic affects.

Plainly the same criteria we have already established for language hold good here. A Michael Angelo painting or a Dutch portrait contains more of external reality than a Picasso, just as a story contains more than a poem. But what is the scope and degree of the emotional reorganisation in the visual that it effects? It is chiefly on this that the varying estimates of greatness in painting are based. Just as in music or poetry, so in painting, easy solutions or shallow grasps of reality are poor art.

Painting resembles poetry in this much, that the affects do not inhere in the associations of the things, but in the lines and forms and colours that compose them. Certain scenes – for a funeral, – have affective associations in themselves. But the affective associations used by painting do not pertain to the funeral as an event but to a brownish rectangle in a large transparent box with circles at the end drawn by greyish ere horeshapes. The affective associations adhering to ideas of bereavement could quite properly be used in a story, and the novelist could legitimately bring in a funeral in order to utilise its affective associations in his pattern. Again the mere word “funeral” as a word has of course inherent affective associations which can be used in poetry – the “funeral of my hopes” – only if it is thoroughly understood that whole group of such linguistic associations will be brought into the poem, and must either be utilised or inhibited, e.g. suggestions of darkness, of purple, of stuffy respectability, of a procession, or pomp and ceremony, of deep wells (sound association with funnel plus grave). The affective associations used by painting have only those of colour, line and combinations of colour and line, but they are used to organise the meaning – the real object represented.

Hence the static plastic arts which are representational are akin to poetry and mathematics – to the classificatory sciences and the universal arts. Just as we slip at once into the “I” of the poem, so we slip at once into the viewpoint of the painter. We see the world both from where the poet and where the painter stands.

We have already explained why this approach leads to a “tribal” primitive attitude to living, why it tends to lead to the realisation of a static universal human essence opposed to a static nature, and is therefore the best medium for voicing universal cries of passion or insight. By a paradox which is not really a paradox, but is given in the nature of individuation, poetry and painting are also the best mediums for expressing individuality – the individuality however only of the poet. Painting, poetry and melody all have this in common – this timeless universal quality of the human genus rather than the interesting sub-complications of a group of human individuals. Hence too we find painting developed at an early stage in the history of civilisation – as early as Palaeolithic man.

In its first appearance painting is man’s consciousness of affective quality in Nature, hence the “life-like” character of early Palaeolithic Art, when it deals with natural subjects. But with the development of man from a group of hunters and food-gatherers to a crop-raising and cattle-rearing tribe, man passes from a co-operating observation of Nature, seeking his own desires in it, to a co-operative power over Nature, by drawing it into the tribe and domesticating it. Hence he is now interested in the power of social forms over reality, which becomes “convention” in perceptual rendering. Therefore naturalistic Palaeolithic Art becomes in Neolithic days conventional, arbitrary and symbolic – decorative. Not only does this prepare the way for writing, but it also expresses a psychic change in culture similar to the passage from rhythm to poetry and to melody.

The passage from the gens or tribe to class society is marked by a further differentiation in pictorial art which takes the form of a return of “naturalism,” but man now seeks in Nature, not the affective qualities of the solid tribe, but the heightened and specialised qualities of the ruling class. These are elaborated by the division of labour and the greater technical power and penetration of Nature this makes possible. This naturalism is always ready to fall back into “conventionality” when a class ceases to be vitally in touch with active reality and its former discoveries ossify into dry shells. Naturalism becomes academicism. The most naturalistic pictorial art is bourgeois art, corresponding to its greater productivity and differentiation and more marked division of labour. Hence the rise of naturalism in bourgeois art, and its revolutionary self-movement, is connected with the rise of harmony in music and of the evolutionary sciences generally during the same period. Naturalism must not be confused with realism – for example the realism of bourgeois Flemish painting. This realism too may be conventional. Since painting is like poetry, and not the novel, the vital ego-organisation which is the basis of naturalism does not take place in the real world depicted, but flows from the complex of memory-images and affective reverberations awakened by the line or colour, and is organised by the “meaning,” by the projective characteristics of the painting.

In later bourgeois culture economic differentiation becomes crippling and coercive instead of being the road to individuation of freedom. There is a reaction against content, which, as long as it remains within the bourgeois categories, appears as “commodity-fetishism.” The social forms which make the content marketable and give it an exchange value are elevated as ends in themselves. Hence, cubism, futurism, and various forms of so-called “abstract” art.

Finding himself ultimately enslaved by the social form and therefore still “bound to the market,” the bourgeois rebel attempts to shake himself free even from the social ego and so to escape into the world of dream where both ego and external world are personal and unconscious. This is surréalisme, with the apparent return of a realism which is however fictitious, because it is not the real, i.e. social external world which returns, but the unconscious personal world. We have already explained why surréalisme represents the final bourgeois position.

The plastic arts are static. A visual art moving in time is provided in the dance, the drama and (finally) the film. The dance is primitive story – quality separating itself from the womb of rhythm. In the dance, rhythm gradually ceases to be physiological and begins to unfold in time and spare the qualitative movement of reality, in which things happen.

Painting shares with poetry the quality of having affects organised by the projective structure of the symbols. (A black oblong, not a coffin.) But directly the visual arts move in time this spatial or pseudo-grammatical organisation is no longer possible and therefore it must take place as in the story – the affective organisation is an organisation of the real object symbolised by the visual representation. (The real coffin.) The courtship of the dance, the murder on the stage, the riot on the films are the material which is affectively organised, and not the linked forms, prostrate figure, or scattered crowd, considered as a projective structure, as would be the case if they were frozen into a static tableau. This confusion between the projective organisation of the static arts and the real organisation of the temporal arts leads to all kinds of special expressionistic and scenic theories of drama – for example those of Edward Gordon Craig. The development of the ballet, the drama and the film is the equivalent of the development of harmony, of the counterpoint of individuals whose life-experiences criss-cross against a changing background of Nature because the division of labour has wrought a similar differentiation and individuation within the crystal of the collective tribe. Tragedy appears in the rapid evolution of Greek classes out of the Greek gens and blossoms again with the rise of bourgeois productivity in the drama of the Elizabethan stage. In both, poetry still soaks it because the drama is a transitional stage in class society. It is the product of a society passing from collectivity to individuality.

The dance, the drama and the film are mixed or counterpointed in their technique as compared to the affective organisations of language and music. Just as music’s sounds are the objects of external reality and not symbols of such objects, so the dancing or acting human being or the scenery around him is the real object. Admittedly, the dancing or acting human being also refers to another object (the courting or dying human he mimics). But he is also an object of external reality in himself – a gracefully- or attractively-moving human being. Hence acting and dancing have a musical “non-symbolical component,” but they also have the other component, the characteristic of referring to objects of external reality. There is a double organisation – the thing mimicked and the person mimicking. This double organisation has a certain danger, and gives rise to a quarrel between actor and author, cast and producer, which can to-day only be overcome in the film, where the mechanical flexibility of the camera makes the cast wax in a good producer’s hands. However in an era of bourgeois individualism this feature of the film cannot be fully explored, and the film remains a “starring” vehicle, except in Soviet Russia.

The dancer or actor as himself, as an object of contemplation, is static, like the poetic word. The reality symbolised is like the reality of story’s objects – in movement. Hence there is a tension in a play or film between the static close-up or actor’s instant and the moving action or author’s organisation – this resembles the tension in an epic between the poetic instant and the narrative movement.

The individual passages in epic or play that we conceive of as particularly poetic or histrionic – Homer’s description of the stars of heaven opening out, or the great moment of a Duse – are almost like music: the affects are attached to the words or actions and only released by the meaning, as if a dam had burst. The play or epic halts. There is a poetic instant and as time vanishes, space enters; the horizon expands and becomes boundless. The art reveals itself as double. The things described in turn have their own affects which are organised by the action of the story or the play in time. It is this that makes us think of the Iliad and the Odyssey as substantial and spacious worlds, stretching back as far as the eye can reach. In the great Shakespearean plays we feel this double organisation as a world of vast cloudy significance, not only looming vaguely behind the action but in the poetic passages actually casting lights on it from underneath, so that the action itself is subtly modified and. glows with unexpected fluorescence. Hence the difficulty of acting poetic plays. Action and poetry go together because they live in different structures. But poetry and acting – the “I” of the poet and the “I” of the actor, are in the same structure and blot each other out. Irving’s “Hamlet,” or Shakespeare’s – we have to choose. In a play which is read, poetry can take the place of acting, hence the satisfaction from reading Shakespeare’s plays not to be paralleled by reading Ibsen’s. Of course in Shakespeare’s time the actor was less dominating, as is shown by the use of boys to take women’s parts.

The same characteristic and good mixture of the real and symbolised objects which is to be found in dance and drama is to be distinguished from the same mixture occasionally found in music – the bastard kind of music in which nightingales sing, monastery bells toll, and locomotives whistle. These real objects, mimicked or symbolised by sound, disturb the logical self-consistent structure of music’s world, and are therefore here impermissable.

In Palaeolithic Art the individual is only self-conscious and is still anchored in the perception of the object, giving rise to an atomic naturalism of exactly-portrayed, unorganised percept-things. So in the dance of hunting primitives, the natural object – the animal – is mimicked unaltered because it is only sought by man, not changed. The object draws the ego out of man in accurate perception. It is gained in co-operation and so becomes conscious, a fact which differentiates its qualities from those it possesses in brute perception, but it is sought, not created.

In Neolithic Art, when hunting or food-gathering man becomes a crop-raising or cattle-rearing tribe, the object is not merely sought by society but changed by it. The man realises himself in the percept as social man, as the tribe changing the object according to conventions and forms rooted in the means of communication. The dance becomes the formal hieratic movement of chorus and incipient tragedy. The hunting or food-gathering primitive’s dance is violently naturalistic and mimicking; the food-raising or cattle-rearing dance has the formality of a religious rite and reveals the impress of the tribe’s soul on Nature. It emphasises the magical and world-governing power of the gesture. The circling sun obeys the circling dancer; the crop lifts with the leaping of young men; life quickens with the dizzy motion. The tribe draws Nature into its bosom.

The elaboration of class-society causes the dance to develop into a story, into a play. The intricacies of the chorus loosen sufficiently to permit the emergence of individual players. Individuation, produced by the division of labour in a class society, is reflected in the tragedy. A god, a hero, a priest-king, people, great men, detach themselves from the chorus and appear on the stage, giving birth simultaneously to the static acting and the moving action which were inseparably one in the danced chorus, just as were the static poem and the moving story one in the ritual chant, where the word is poetically world-creating and yet also relates a mythical story.

Of course the decay and rigidity of a class society is at any moment reflected in a stiffening and typification of the “characters.” The individuation is not rooted in the class but in the division of labour. The class cleavage at first makes this division possible but at a certain moment denies its further development and becomes a brake, a source of academic ossification, a corset which society must break or be stifled.

We said that the cathedrals were bourgeois and not feudal, that they were already Protestant heresies in the heart of Catholicism, the bourgeois town developing in the feudal country. Hence the bourgeois play begins in the cathedrals as the mystery play frowned on by the Church authorities. When the monarchy allies itself with the bourgeois class, the mystery moves to court and becomes the Elizabethan tragedy. Here the individual is realised once again naturalistically as the prince, as the social will incarnate in the free desires of the hero.

Because of the special development of bourgeois individuality, after Shakespeare the mimed action falls a victim to the static actor. In Greek tragedy the actor is swaddled in the trappings of cothurni and mask; he is the pure vehicle of poetry and action. In the Elizabethan play the actor’s personality is still stifled, and because the actor is subordinate to the mimed action the play is still poetic. In our day the actor’s instant conflicts with the poets; in Shakespeare’s the boy-woman, muffled in the collective representations of the feudal court, was still a hollowness which gave room for the poetry of Cleopatra to come forward and expand. The incursion of woman on to the stage marks the rise of acting in the drama, and the death of narrative and poetry. The personal individual actor or actress becomes primary.; his social relations with others or with the social ego – which constitute the story or poetry of the play – become secondary. The play, because of the collective basis of its technique, is injured by the individualism of bourgeois culture.

The play, like painting, becomes increasingly realistic and then moves over to commodity-fetishism – the abstract structure of Expressionism in which the conventions or social forms are hypostatised, and the content or “story” is expelled, so that the play aspires towards the impossibility of becoming the pure social ego. And the play finally makes a bid to cut itself off both from social ego and external reality according to the mechanism of surréaliste dream-work.

This same basic movement is only what we have already analysed in poetry. For the cry, reproducing the authentic image (the bird call or animal cry) in the dance of the hunting primitive, becomes the elaborate chant or choral hymn, with strophe, antistrophe and epode, in the crop-raising or pastoral society which has sucked Nature into its undifferentiated bosom. The rise of class society and its individuation, based an division of labour, is reflected in the emergence of the bard, with his epic poetry, glorifying the deeds of heroes, stories in which he does not speak for himself but for a general class, and so his own personal instant does not conflict with a poetic instant which is only given in the acts of heroes. But the further individuation of society, due to still greater division of labour, gives rise to the poet, with his lyrical verse – amatory, epistolary and personal – in which the poetic instant coincides with the personal instant, in which the collective “I” (formerly general and heroic) has become personal and individual. With this goes a naturalism and “pathos” of the kind for which Euripides was reproached by his contemporaries and which seems to bourgeois culture so appealing and right.

The poet finds his full individuation in bourgeois poetry, where chanted lyrical poetry becomes written study poetry, and the social ego of poetry is identified with the free individual. Here too there is movement through naturalism to escape from the external world (symbolism) and escape also from the social ego (surréalisme).

Architecture and the “applied” arts (ceramics, weaving, design of clothes, furniture, machines, cars, printed characters and the like) play a rôle in the visual field similar to that of music in the aural field in that the “things” are parts of external reality and are “distorted” or organised directly by the affects. But architecture and the other arts are like inverted music. The “external” element is not a formal ideal “structure” as in music, with its pseudo-logical laws, but a human and social function. The external reality of a house or vase is its use – its coveringness or its capaciousness. This use-form is organised or distorted affectively either by the symbolisation of natural external reality (as when a carpet, vase or house is covered with sculpture or decoration) or when it is given shape, balance, harmony, curves and movement in space. This organisation is poetic; the “I” which organises the use-function is static and collective. Great architecture arises in the womb of a society where social “I” and individual “I” do not conflict but reinforce each other.

Hunting man expresses the use-value realistically. He finds in Nature the correspondence to his use. His house is a cave; his vase a gourd; his weapon a rough flint; his covering a skin. In this sense his applied art is as realistic as his drawings.

Crop-raising or pastoral man imposes on his materialised use-value a decoration which is conventional and distorting. He takes Nature into the bosom of the tribe, and moulds it plastically to his wish. The use-value is given a social form – it is minted. The stone implements are polished. Instead of seeking out a cave, he erects a rough hut in a convenient spot. He no longer clothes himself in skins; his covering is woven. Instead of gourds, he uses pottery, moulded to a shape and decorated.

The birth of a class society sees the birth of palaces and temples where “coveringness” is affectively organised to express the majesty and sacredness of a ruling class. This majesty and sacredness has accrued through the division of labour and the alienation of property whereby the increased social power seems to gather at the pole of the ruling class at the same time as the humility and abasement appears at the pole of the slave class. With the merchant class of Athens and Rome this reflects itself also in municipal buildings. In feudal society castles and basilicas express the affective organisation of social power. The cathedral and the hôtel de ville of medieval town life already reflect the growing power of the bourgeois class and are rebellious. The bourgeois class is still collective – it is gathered in self-governing and self-arming communes – tribal islands in the pores of feudalism. At first their social expansion appears in the palaces and cathedrals of princes, who wield for a time the power of the bourgeoisie against other feudal powers. Then it passes into aristocratic villas and State structures; finally, it appears in the form of gentlemen’s residences. At first this is a naturalistic movement. Houses become less “formal” and more useful and domestic. This movement too passes into abstraction. Abstraction in painting is functionalism in architecture. Finally even the social ego is negated and architecture shows everywhere freakishness and personal whim, irrespective of the needs of function. The same movement of course takes place in ceramics, textiles and other applied arts. In general the products of a class society in this field show the same rich elaboration and aesthetic idealisation of the aims and aspirations of the ruling class as do the other forms of art.

The organisation of the arts can be shown schematically:

| ART | EXTERNAL REALITY |

| I. SOUND: | |

| Music | Pseudo-Logical Laws of Musical Structure |

| Poetry | Syntactical and Grammatical Laws of Language |

| Story | Real External World described |

| II. VISUAL: | |

| Painting and Sculpture | Projective Laws of Structural Representation |

| Dance and the Play and Film | Real Action imitated by Real People |

| Architecture | Use-Function |

| Ceramics, Textiles, Furniture, etc. | |

Obviously the arts can also be arranged historically – beginning from their confused appearance in food-gathering- and hunting-man to their complex development in a class society where individuation is possible. We have already dealt with this movement in general. The three main periods are all sublated in modern art’s methods of subjective organisation which therefore include the consciousness of man seeking himself in Nature, of man drawing Nature into the social but undifferentiated “I” of the tribe, and finally of man splitting the social “I” into living individuals and at the same time resolving Nature into a differentiated universe which evolves.

If we are asked the purpose of art, we can make an answer – the precise nature of it depending on what we mean by purpose. Art has “survived”; cultures containing art have outlived and replaced those that have not, because art adapts the psyche to the environment, and is therefore one of the conditions of the development of society. But we get another answer if we ask how art performs its task, for it does this by taking a piece of environment and distorting it, giving it a non-likeness to external reality which is also a likeness to the genotype. It remoulds external reality nearer to the likeness of the genotype’s instincts, but since the instinctive genotype is nothing but an unconscious and dynamic desire it remoulds external reality nearer to the heart’s desire. Art becomes more socially and biologically valuable and greater art the more that remoulding is comprehensive and true to the nature of reality, using as its material the sadness, the catastrophes, the blind necessities, as well as the delights and pleasures of life. An organism which thinks life is all “for the best in the best possible of worlds” will have little survival value. Great art can thus be great tragedy, for here, reality at its bitterest – death, despair, eternal failure – is yet given an organisation, a shape, an affective arrangement which expresses a deeper and more social view of fate. By giving external reality an affective organisation drawn from its heart, the genotype makes all reality, even death, more interesting because more true. The world glows with interest; our hearts go out to it with appetite to encounter it, to live in it, to get to grips with it. A great novel is how we should like our own lives to be, not petty or dull, but full of great issues, turning even death to a noble sound:

Notre vie est noble et tragique

Comme le masque d'un tyran

Nul drame hazardeux et magique

Aucun détail indifferent

Ne rend notre amour pathetique[1]

A great picture is how we should like the world to look to us – brighter, full of affective colour. Great music is how we should like our emotions to run on, full of strenuous purpose and deep aims. And because, for a moment, we saw how it might be, were given the remade object into our hands, for ever after we tend to make our lives less petty, tend to look around us with a more-seeing eye, tend to feel richly and strenuously.

If we ask why art, by making the environment wear the expression of the genotype, comes to us with the nearness and significance it does, we must say still more about art’s essence. In making external reality glow with our expression, art tells us about ourselves. No man can look directly at himself, but art makes of the Universe a mirror in which we catch glimpses of ourselves, not as we are, but as we are in active potentiality of becoming in relation to reality through society. The genotype we see is the genotype stamped with all the possibilities and grandeur of mankind – an elaboration which in its turn is extracted by society from the rest of reality. Art gives us so many glimpses of the inner heart of life; and that is its significance, different from and yet arising out of its purpose. It is like a magic lantern which projects our real selves on the Universe and promises us that we, as we desire, can alter the Universe, alter it to the measure of our needs. But to do so, we must know more deeply our real needs, must make ourselves yet more conscious of ourselves. The more we grip external reality, the more our art develops and grows increasingly subtle, the more the magic lantern show takes on new subtleties and fresh richnesses. Art tells us what science cannot tell us, and what religion only feigns to tell us – what we are and why we are, why we hope and suffer and love and die. It does not tell us this in the language of science, as theology and dogma attempt to do, but in the only language that can express these truths, the language of inner reality itself, the language of affect and emotion. And its message is generated by our attempt to realise its essence in an active struggle with Nature, the struggle called life.

All this is only the inverse picture of what science does. Science too has a survival value and a purpose, and it fulfils this by adapting external reality to the genotype just as art adapts the genotype to external reality. Just as art achieves its adaptative purpose by projecting the genotype’s inner desires on to external reality, so science achieves its end by receiving the orderings of external reality into the mind, in the phantastic mirror-world of scientific ideology. Necessity, projected into the psyche, becomes conscious and man can mould external reality to his will. Just as art, by adapting the genotype and projecting its features into external reality, tells us what the genotype is, so science, by receiving the reflection of external reality into the psyche, tells us what external reality is. As art tells us the significance and meaning of all we are in the language of feeling, so science tells us the significance of all we see in the language of cognition. One is temporal, full of change; the other spatial and seemingly static. One alone could not generate a phantastic projection of the whole Universe, but together, being contradictory, they are dialectic, and call into being the spatio-temporal, historic Universe; not by themselves but by the practice, the concrete living, from which they emerge. The Universe that emerges is explosive, contradictory, dynamically moving apart, because these are the characteristics of the movement of reality which produced it, the movement of human life.

Art and science play contradictory and yet intermingled rôles in the sphere of theory. Science in cognition gives art a projected selection from external reality which art organises and makes affectively appealing, so that the energy of the genotype is directed towards imposing its desires on that external reality. Thus, attention, moving inwards from action, through art moves outwards again to action. Attention to change of externals causes the inward movement of cognition; attention to change of internals the outward movement of action. For the outward-moving energy to effect its aim, science is again needed, and the original memory-images, now modified affectively, must be rescanned to grasp their inner relationships so that the desires of the genotype can be effected. Science in cognition now becomes science in action. In effecting those desires with the aid of existing memory-images, more knowledge is gained of the real orderings of external reality. Its object achieved, attention returns with fresh empirical experience to add to its treasure. This richer content is again organised affectively by the genotype, and again flows outwards as energy directed to an end. Energy is always flowing out to the environment of society, and new perception always flowing in from it; as we change ourselves, we change the world; as we change the world we learn more about it; as we learn more about it, we change ourselves; as we change ourselves, we learn more about ourselves; as we learn more about what we are, we know more clearly what we want. This is the dialectic of concrete life in which associated men struggle with Nature. The genotype and the external reality exist separately in theory, but it is an abstract separation. The greater the separation, the greater the unconsciousness of each. The complete separation gives us on the one hand the material body of a man, and on the other hand the unknown environment. Spreading from the point of interaction, the Psyche, two vast spheres of light grow outwards simultaneously; knowledge of external reality, science; knowledge of ourselves, art. As these spheres expand, they change the material they dominate by interaction with each other. The conscious sphere of the genotype takes colour from the known sphere of external reality and vice versa. This change – change in heart, change in the face of the earth – is not just a consequence of the expansion of the two circles, it is the two expansions, just as the flash of light is the electromagnetic wave group. As man becomes increasingly free and therefore increasingly himself by growing increasingly conscious of Necessity, so Necessity becomes increasingly orderly and “law-abiding,” increasingly itself, as it falls increasingly within the conscious grasp of the genotype.

Art therefore is all active cognition, and science is all cognitive action. Art in contemplation is all active organisation of the subject of cognition, and in action all active organisation of the object of cognition. Science in contemplation is all cognitive organisation of the subject of action, and in action all cognitive organisation of the object of action. The link between science and art, the reason they can live in the same language, is this: the subject of action is the same as the subject of cognition – the genotype. The object of action is the same as the object of cognition – external reality. Since the genotype is a part of reality, although it finds itself set up against another part of it, the two interact; there is development; man’s thought and man’s society have a history.

Art is the science of feeling, science the art of knowing. We must know to be able to do, but we must feel to know what to do.

Art is born in struggle, because there is in society a conflict between phantasy and reality. It is not a neurotic conflict because it is a social problem and is solved by the artist for society. Psycho-analysts do not see the poet playing a social function, but regard him as a neurotic working off his complexes at the expense of the public. Therefore in analysing a work of art, psycho-analysts seek just those symbols that are peculiarly private, i.e. neurotic, and hence psycho-analytical criticism of art finds its examples and material always either in third-rate artistic work or in accidental features of good work. In Hamlet they see an Oedipus-complex; but they do not see that this does not explain the universal power of the great speeches, or the equal greatness of Antony and Cleopatra, which cannot be analysed into an Oedipus complex.

The psycho-analyst can sometimes cure the neurotic who cannot cure himself unaided, because he provides a force or point of leverage outside the psyche of the neurotic. He is a member of society, and can therefore work from the outside inwards, into the socially created conscious psyche, the neurotic’s “better self,” and so attack the unconscious, his “worse self.” The better self, the conscious psyche, the conscience, is society’s creation, while the “worse self” is genotypical, the animal in us.

The psycho-analyst is only one man, and is also the possessor of a worse self which may get between himself and his patient. He is a luxury who can be afforded only by the well-to-do. In art, all society, the sum of all conscious psyches engaged in social creation, speaks to a man’s “better self.” All the better part of humanity, endlessly attacking and solving life’s problems, stands ranged behind the artistic culture of a nation. They are men not gods; like him they suffered and fought, but when they died they left behind the enduring essence of their transitory lives. Hence the consoling, healing and invigorating power of art.

The emotional attitude of the neurotic or the psychotic towards reality is permanent. That of the poet in creation, or the reader in experiencing, is temporary. The essence of genuine illusion is that it is non-symbolic and plastic. The neurotic is deluded because the complex is in his unconscious; he is unfree. The artist is only illuded because the complex is in his conscious; he is free. We take up the attitude when reading a poem, and experience the emotions, and then when the poem has been experienced the attitude is thrown away. The attitude was released by the conscious emotions; as the neurotic attitude may be unfrozen if he becomes conscious of the complex; as the sleeper wakes if the stimulus demands willed-action. The artist releases the autonomous complex in a work of art and “forgets” it, goes on to create anew, to experiment again with the eternal adaptation of the genotype to its eternally changing environment. If poetry becomes religion, if the non-symbolic is taken to be symbolic, the emotional attitude becomes frozen like the neurotic attitude. Thus the value of poetry’s illusions in securing catharsis, as compared to religion’s, is that they are known for illusion, and as compared to dream, that they are social.

If poetry’s emotional attitudes pass, what is their value? It is this; experience leaves behind it a trace in memory. It is stored by the organism and modifies its action. The Universe to-day is not what it was a million years ago, because it is that much more full of experience, and that much more historic. Society is not what it was two thousand years ago, because its culture has lived through much and experienced much. So too a wise man, in the course of his life, has endured and experienced.. He has not acquired knowledge of external reality only, for such a man we call merely “learned,” and think of his learning as something arid, devoid of richness. The wise man has also learned about himself. He has had emotional experience. It is because of this double experience that we call him wise, with a ripeness, a poise, a sagacity given to him by all his history. Of course neither science nor art are substitutes for concrete living: they are guide-books to it.

The wisdom of a culture, our social heritage, inheres both in its science and its art. Either alone is one-sided wisdom, but both together give ripe sagacity, the vigour and serenity of an organism sure of itself in the face of external reality.

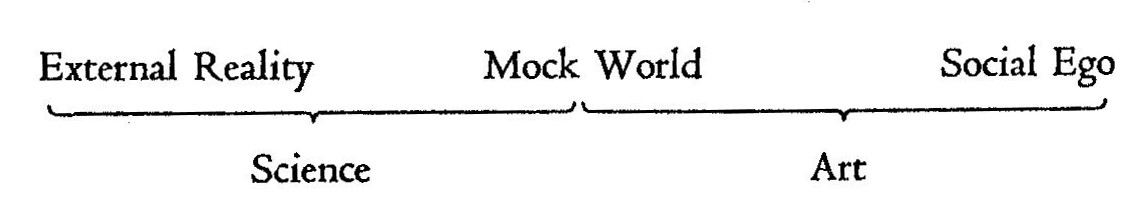

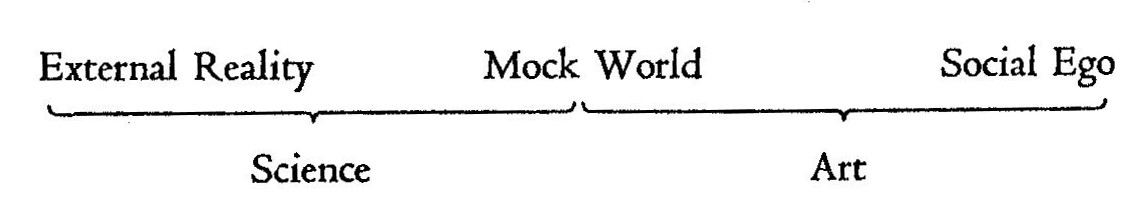

What, then, is the illusion of art? In what does it consist? Not in the affective element, for artistic emotion is consciously experienced, and is therefore real and true. Real and true as applied to emotion mean, simply: Has it existed in reality? – Has it been present in a psyche? The emotion of poetry is certainly real in this sense. The illusion of poetry must therefore inhere in the piece of external reality to which the emotion is attached – in poetry to the meaning, in novel to the story. The purpose of this piece of external reality was to provide a subject for the affect, because an affect is a conscious judgment, and must therefore be a judgment of something. Art is therefore affective experimenting with selected pieces of external reality. The situation corresponds to a scientific experiment. In this a selected piece of external reality is set up in the laboratory. It is a mock world, an imitation of that part of external reality in which the experimenter is interested. It may be an animal’s heart in a physiological salt solution, a shower of electrified droplets between two plates, or an aerofoil in a wind tunnel. In each case there is a “fake” piece of the world, detached so as to be handled conveniently, and illusory in this much, that it is not actually what we meet in real life, but a selection from external reality arranged for our own purposes. It is an “as if.” In the same way the external reality symbolised in scientific reasoning is never all external reality, or a simple chunk of it, but a selection from it. The difference between art’s piece of reality and science’s is that science is only interested in the relation of that selected piece to the world from which it is drawn, whereas art is interested in the relation between the genotype and the selected piece of reality, and therefore ignores the whole world standing behind the part. If by the words “mock world,” we denote the illusory piece of external reality, the symbolical part alike of poetry and science, we get this relation:

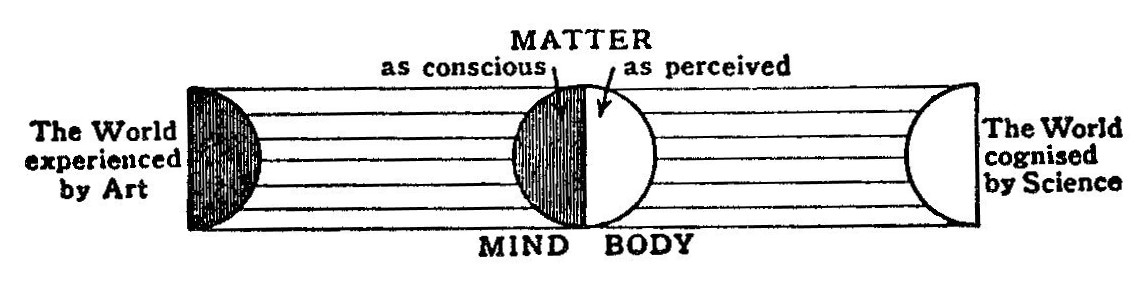

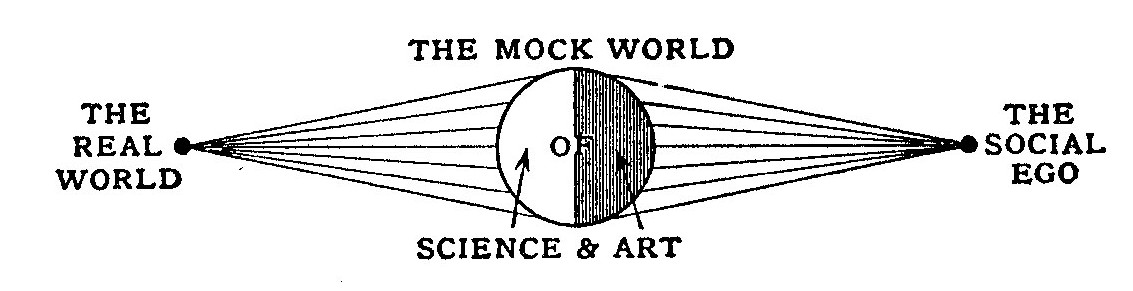

Hence it is just “illusion” that art and science have in common. The distinctive concern of science is the world of external reality; art is occupied with the world of internal reality. The ordering or logical manifold characteristic of scientific language is that internal structure in its mock world projected from the relationships of external reality. The ordering or affective manifold characteristic of artistic language is that internal structure in its mock world projected from the relationships of internal reality. Hence another schematic representation:

But since the genotype is itself a part of external reality, we can also represent it thus:

Hence science and art together are able to symbolise a complete universe which includes the genotype itself. Each alone is partial, but the two halves together make a whole, not as fitted together, but as they interpenetrate man’s struggle with Nature in the process of concrete living.

1. Apollinaire.